In loving memory of my dear husband Adolphus Meheux, late donkeyman, lost at sea on

May 17th 1917.

A loving husband and father, true and kind;

A beautiful memory left behind.

From his loving wife and children, brother and sister in-law (George and Vi), Jenny Stafford, and Grandma Brown.[1]

|

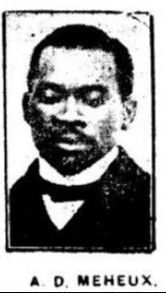

Adolphus Meheux was a Black seaman living in Hull in the early part of the twentieth century. He moved to the region from Sierra Leone, married Agnes a local Leeds woman and had five children.[2] During the First World War, Meheux joined the Merchant Marine; however, he did not live to see the end of the conflict tragically dying on board the S.S. Cito which was sunk in 1917 by German destroyers.

On 12 May 1917 Adolphus left his home in Harrow Street, Hull and boarded the S.S. Cito (pictured above). [3] The war provided a rich source of employment for Black seamen who had suffered a turbulent time competing for jobs in the pre-war years.[4] In 1911, Havelock Wilson and the Seaman’s Union campaigned for British sailors to be employed on British ships.[5] They also promoted wage controls which meant that it was no longer the cheaper option to employ Asian or African sailors over their British counterparts.[6] Like most African seamen, Adolphus had taken employment in one of the less desirable positions on board a steamship. At the end of the nineteenth century a shipboard hierarchy had been constructed, the general rule was that the closer a person was to the waterline the lower their social standing. Thus, non-white seamen typically occupied positions in the engine room, although some of them

|

A 'Donkeyman' was a man who had responsibilities in the engine room of a vessel. |

were cooks. Adolphus was a ‘donkeyman’ but other African and Black seaman were often trimmers or firemen.[7] Although these positions were typically undesirable for white sailors, for men from tropical regions the heat may have provided some solace from the bitterly cold European climates experienced on deck.

Once the vessel had her full complement of crew, the Cito embarked from the port of Hull and made her way to Yarmouth Roads in London to meet with a convoy. At 3.20 p.m. Adolphus and the Cito set sail for Rotterdam.[8] The first five days of the voyage were relatively uneventful. The convoy had parted company and the sailors were preparing the ship to drop anchor in the Netherlands. However, at 11.45 p.m. on 17 May 1917 while the vessel was encased in a dense fog, the crew heard the alarming sound of gunfire. Before they had time to react they were surrounded by two German destroyers which were no more than one hundred yards away from the vessel. To their horror the Cito had been badly damaged and had begun to sink. Chaos broke out on deck and bullets rained down on the sailors costing some of the men their lives. Other members of the crew had managed to launch a small boat into the water and get on board before the vessel was completely submerged in water.[9]

Unfortunately, Adolphus did not escape with his life. Instead he joined the many sailors who died because of international conflict during the twentieth century. It is unclear whether he was shot on the deck or if he drowned when the vessel sank to the bottom of the ocean. However, the latter is more probable. Adolphus’s vulnerable position in the ship meant that if he was working in the engine room when the vessel began to sink he stood very little chance of getting up onto the deck.

Adolphus was only forty years old when he died, and like many men who lost their lives in the First and Second World Wars, he left a wife and children behind. Fortunately, Agnes Meheux received £300 compensation for her husband’s death.[10] This amount was the equivalent to approximately £23,600 today. Although the money was no consolation for their loss, by early-twentieth-century standards the Meheux family were fortunate to receive anything from the government. Disgracefully, not all families of foreign non-white sailors were given compensation. It was only awarded for the death or injury of ‘British nationals domiciled in the colonies and protectorates,’ which meant that if a person’s place of birth could not be proven, no money would be issued.[11] This strongly affected African sailors who had perished either in the merchant marine, Navy or in the many theatres of war around Europe.

|

Fortunately, the Meheux family were able to prove Adolphus’s birthplace because of his father’s prominence in Sierra Leone. In 1861 John Meheux (pictured in the photograph to the left, in the centre wearing a top hat) had been appointed the Sheriff of Sierra Leone by the Queen.[12] Unfortunately, John had died when Adolphus was six but nevertheless his ties to Africa were arguably irrefutable.

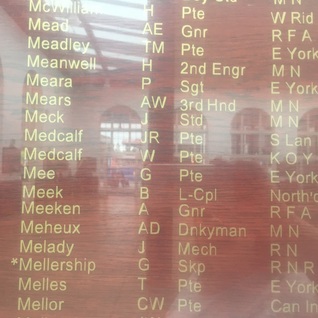

During the First World War, 3,305 vessels were sunk and almost 17,000 merchant seamen lost their lives.[13] Their names have been etched into the Tower Hill Memorial in London as an acknowledgement of the pivotal role they played in Britain’s war effort. |

Adolphus Meheux’s name can be found among them as well as on the memorial boards surrounding the entrance of Hull train station (see below).

Meheux may have lost his life in the Great War, but his name will be forever listed among Britain and Hull’s First World War casualties and therefore he will not be forgotten. He also left five children in Hull, who all contributed to the collective African presence in the region.

Meheux may have lost his life in the Great War, but his name will be forever listed among Britain and Hull’s First World War casualties and therefore he will not be forgotten. He also left five children in Hull, who all contributed to the collective African presence in the region.

Thanks go to Mike Covell for providing us with the image of Adolphus Mehuex above.

Footnotes

[1] Hull Daily Mail, 17 May 1918.

[2] Adolphus's children were Ralph Benjamin, Norah Florence, Clarice Frances, Agnes Eveline and Adolphus Reginald. In 1911 the family where living at 42 Harrow Street, off Hull Road. 1911 England Census.

[3] Crew list for the Cito, http://1915crewlists.rmg.co.uk/document/190359 accessed 20/10/16

[4] Diane Frost, Work and Community Among West African Migrant Workers since the Nineteenth Century (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1999) p. 61

[5] R. Costello, Black Salt: Seafarers of African Descent on British Ships (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2012), p. 138.

[6] Ibid, p. 138.

[7] Crew list for the Cito, http://1915crewlists.rmg.co.uk/document/190359 accessed 20/10/16

[8] Hull Daily Mail, 25 June 1917, p. 2.

[9] Ibid, p. 2.

[10] Hull Daily Mail, 11 July 1917, p. 2.

[11] R. Costello, Black Salt, p. 144.

[12] Dublin Evening Mail, 10 August 1861, p. 3.

[13] Commonwealth War Graves Commission, http://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery accessed 23/10/2016

[1] Hull Daily Mail, 17 May 1918.

[2] Adolphus's children were Ralph Benjamin, Norah Florence, Clarice Frances, Agnes Eveline and Adolphus Reginald. In 1911 the family where living at 42 Harrow Street, off Hull Road. 1911 England Census.

[3] Crew list for the Cito, http://1915crewlists.rmg.co.uk/document/190359 accessed 20/10/16

[4] Diane Frost, Work and Community Among West African Migrant Workers since the Nineteenth Century (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1999) p. 61

[5] R. Costello, Black Salt: Seafarers of African Descent on British Ships (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2012), p. 138.

[6] Ibid, p. 138.

[7] Crew list for the Cito, http://1915crewlists.rmg.co.uk/document/190359 accessed 20/10/16

[8] Hull Daily Mail, 25 June 1917, p. 2.

[9] Ibid, p. 2.

[10] Hull Daily Mail, 11 July 1917, p. 2.

[11] R. Costello, Black Salt, p. 144.

[12] Dublin Evening Mail, 10 August 1861, p. 3.

[13] Commonwealth War Graves Commission, http://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery accessed 23/10/2016