An adage often stated by genealogists is that uncovering the lives of those of African descent during the eighteenth century is like searching for a needle in a haystack. Narratives by Olaudah Equiano and James Albert Gronniosaw may offer first-hand accounts of black life in the British Isles, but writings by Blacks in this era are relatively rare. And while historians such as Miranda Kaufman, Kathleen Chater, and Gretchen Grezina have done an excellent job describing Black life in the Age of Slavery, there has been little scholarship regarding those of African descent in Yorkshire. [1] Thus, the benefit of this website.

By the end of the American War of Independence, approximately 10,000 Blacks are estimated to have been living in the British Isles. The bulk of them, many of whom were former seamen from Britain’s colonies, resided in London, Liverpool and Bristol. [2] Evidence of black lives in these large ports can be found in criminal records, church records and newspaper dispatches. [3] Unfortunately, there is a paucity of such records concerning Yorkshire Blacks. This being so, how else might we understand Black lives in Yorkshire in the eighteenth century?

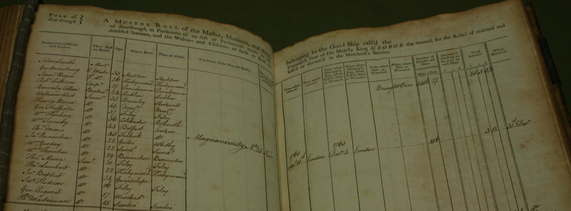

One set of documents does provide information, albeit of a limited nature, on Africans in Yorkshire --- ship musters. In the eighteenth century, British seamen, with certain specified exceptions, were required to pay 6 pence per month from their wages to support the Greenwich Hospital for disabled and retired seamen. [4] To ensure collection of the Seamen’s Sixpence assessments, musters recorded every ship’s crew. The musters noted the names, ranks, place of birth, residence, ship, voyage and wages of each seaman. See Figure 1. The detail of such records offers the opportunity to sketch out the nature of Black seamen’s lives in Yorkshire. [5]

In researching an article on Scarborough’s mid-eighteenth century maritime community, I came across evidence of Africans’ presence in the Yorkshire port. Other than Hull, Scarborough is the only Yorkshire port for which 18th-century musters survive. Between 1747 and 1765 ships with more than 25,000 berths entered and left the harbor of Scarborough. The overwhelming majority of these seamen were from Yorkshire or elsewhere in northern Briton. Less than one percent of the sailors were foreign residents and fewer than 10 mariners on these ships were from Bristol or Liverpool. Among Scarborough’s seamen were seven who appear to have been of African descent. Scarborough’s sailors mostly worked on small ships, with crews averaging eight men, and principally made short trips, most less than three months in duration. Scarborough’s ships were notable for the considerable numbers of family members who worked together and for large numbers of older men who served as cooks on the vessels. When combined with a well-run local seamen’s hospital, the port in the mid-18th century provide a social safety net and close kinship network typically not seen in larger British ports. [6]

How would the seven Blacks on Scarborough ships fit into this maritime community?

Initially, it should be noted that only one of the seven men, Robert Slaves, was a Scarborough resident. Slaves only took one voyage from Scarborough and was discharged in London. There is no known record of Slaves returning to Yorkshire or that he owned land in the port, was married or died there. Similarly, the other six Blacks were not baptized, married or owned land in Scarborough. These sailors were either foreign-born, such as Guadeloupe native John Baptist, London residents or of unknown origins. The seven Blacks on Scarborough ships fit the general pattern of Black British seamen in that they came from the Americas, the Cape Verde islands, and most were residents of large British ports. And in contrast to most Scarborough seamen, who typically worked on colliers or coasting vessels with small, six to eight-man crews and whose short voyages enabled them to be home frequently, the seven Blacks who entered Scarborough in the eighteenth century all served on larger vessels with crews of more than twenty seamen. Ships, such as the Prince Frederick, on which Cato Ray and Caspar Suck served, stopped at Scarborough as part of lengthy voyages that could include trans-Atlantic sailing. On these larger ships, the seven Black sailors were part of diverse multi-national and multi-racial crews. The Black seamen thus appear to have only been in Scarborough for the short periods their ships docked in the port. Robert Slaves, John Baptist and the other five Black seamen may have had a pint in local taverns, but their engagement with the town and its maritime community would have been limited. For example, none of them deserted in the port. Their social lives and community ties would have been centered on the ports they resided in and their shipmates they sailed with.

And in an important way, the work of these men on ships docking in Scarborough was also fairly typical of Blacks on Anglo-American vessels of the era. Four of the men served as seamen and none were officers, while Casper Suck and Robert Slaves were cooks and Guadeloupe-born John Baptist worked as a servant. There were many capable Black seamen on British ships at this time. However, few Blacks ever attained officer status. Service in such servile maritime positions as cook and servant reflected and reinforced the view of many whites that Blacks were lesser. [7]

As was true for Blacks in the Royal Navy, these men did not benefit from paying their Seamen’s Sixpence. Although the local Trinity Hospital, supported by such assessments, provided considerable assistance to seamen, those benefits were almost exclusively received by seamen or their families who resided in Scarborough. None of the seven Black seamen were able, as had a number of Scarborough tars, to spend the harsh winter months receiving in-pensions at Trinity Hospital before returning to the sea in the spring. Nor did their widows benefit from the Hospital’s services, as did a good number of the widows of Scarborough resident seamen. Instead, if hurt these men and their families had to rely on their own resources to get by. [8]

Probably the best way of characterizing Blacks’ involvement in Scarborough’s mid-18th century maritime community would be as minimal and peripheral. As was true for Prince Tilley, who was on the Neptune but was discharged at Rotterdam before the vessel reached Scarborough, Scarborough would have had little importance in the lives of black tars. Large British and foreign ports would be more central to the lives of these men. In the years after the War of American Independence it is likely that the number of seamen of African descent docking at Scarborough would have increased. In the last quarter of the 18th century greater numbers of Blacks on ships from the Americas could be found throughout the North Sea region. Sailors of African descent, such as Limbo Robinson, Primus Whitman, Titus Goodwin and Charles Saylor, all sailed from Rhode Island to Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Hamburg and St. Petersburg with several deserting in these cities. [9] How and whether such Black seamen might have made their way to Yorkshire cannot be answered with certainty. Perhaps a review of the Hull musters for the late 18th century might help fill in this gap in our historical knowledge. [10]

Dr. Charles R. Foy is Associate Professor Early American & Atlantic History at Eastern Illinois University. His scholarship focuses on 18th century black maritime culture. A former fellow at the National Maritime Museum & Mystic Seaport, Dr. Foy has published more than a dozen articles on black mariners and is the creator of the Black Mariner Database, a dataset of more than 27,000 18th century black Atlantic mariners. He is completing a book manuscript, Liberty’s Labyrinth: Freedom in the 18th Century Black Atlantic, that details the nature of freedom in the 18th century through an analysis of the lives of black mariners.

Footnotes

- [1] Miranda Kaufmann, Black Tudors: The Untold Story (2017); Kathleen Chater, Untold Histories: Black People in England and Wales (2009); and Gretchen Grezina, Black London: Life Before Emancipation (1995).

- [2] Charles R. Foy, “‘Unkle Somerset’s freedom: liberty in England for black sailors,” Journal for Maritime Research, 13, no. 1 (May 2011): 21-36, http://thekeep.eiu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1023&context=history_fac.

- [3] See e.g., Old Bailey Online, https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/; Chater, Untold Histories, 9-13.

- [4] Scarborough Muster Rolls, 1747-1765, The National Archives, Kew (“TNA”), CUST 91/111-112; Martin Wilcox, “The Poor ‘Decayed’ Seamen of Greenwich Hospital, 1705-1763,” International Journal of Maritime History (“IJMH”) 25, No. 1 (June 2013): 65-90.

- [5] Royal Navy musters provide a similar window into the lives of Black naval seamen. Charles R. Foy, “The Royal Navy’s Employment of Black Mariners and Maritime Workers, 1754-1783,” IJMH 28, no. 1 (Feb. 2016): 6-35, http://thekeep.eiu.edu/history_fac/83/.

- [6] Charles R. Foy, “Sewing a Safety Net: Scarborough’s Maritime Community, 1747-1765,” International Maritime History Journal, XXIV, No. 1 (June 2012): 1-28, http://thekeep.eiu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1012&context=history_fac.

- [7] Douglas Hamilton, “‘A most active, enterprising officer’: Captain John Perkins, the Royal Navy and boundaries of slavery and liberty in the Caribbean,” Slavery & Abolition 39, no. 2 (June 2017), 4-5. See “Naval Scenes or Sketches Afloat, No. 3 Cooking” https://prints.rmg.co.uk/art/503256/naval-scenes-or-sketeches-afloat-no-3-cooking for a depiction of a Black Cook and Steward in the Age of Sail.

- [8] Foy, “The Royal Navy’s Employment of Black Mariners and Maritime Workers, 1754-1783”: Account Book Containing Accounts of Trinity House, 1752-75, ZOX-10-1, North Yorkshire Records Office.

- [9] Welcome Arnold Labor Books, John Carter Brown Library, Providence, Rhode Island.

- [10] Hull Naval Hospital Musters, 1780-1800, TNA ADM 102/421-422.