|

One of the fascinating aspects of this project is the way in which stories that have featured on the website stimulate further contributions as more information becomes available. The story of the Weeks family is one of the more widely known stories locally and features in our current exhibition at the East Riding Treasure House. Through his own contacts Richard Weeks has gained a further insight into the exploits of his father Fred during the Second World War from Caroline Gaden, the daughter of Ron Ford who had been his war-time colleague. Both Ron and Fred appear in the photograph opposite of the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) "Ferry Group 7" standing in front of a Mosquito aeroplane, probably taken at their base in Sherburn in Elmet. Fred had previously been involved in a fatal plane crash in April 1940 that killed 3 whilst working as a civilian flight engineer for Blackburn Aircraft Co, in Brough whilst testing a prototype flying board, the B20. Fred went on to join the ATA in 1942 as a flight engineering officer. The ATA were known as the Ancient and Tattered Airmen (or women) as most had been rejected by the RAF. Ron Ford was born in Hovingham, North Yorkshire and flew from an early age and won a flying scholarship. Ron joined the ATA as a pilot in July 1942 and met Fred almost straight away during training in Luton as described below: "Initially Ron was posted to the Elementary Flying Training School at Barton near Luton. Accommodation was hard to find and when he arrived by train he couldn’t find a bed so he went to the Police Station and asked for help. An officer refused to put him up in the cells and took him to some digs. Ron was nonplussed when the man who opened the door was of African extraction (Fred Weeks), he had never met a person with a different coloured skin to his own, but he ended up happily staying for the few weeks he was posted there." [1] After the initial training the two men worked together at their base in Sherburn in Elmet. In Ron Ford’s logbook the first mention of Fred being Ron Ford’s Flight Engineer is 8th September 1944 when the two of them flew a Halifax bomber from York to Hawarden in Wales. The majority of active airfields were in the east of the country and this flight would have been a damaged bomber being ferried from an active airfield to the safe side of the UK for repair. In reverse they flew new or repaired aircraft back saving "real" pilots for active service. Their base was Sherburn in Elmet and they had known each other since training in 1942. In total there are 18 flights logged as working together. A fascinating insight into their personal chemistry is from the following extract recounted by Caroline Gaden: "Freddie Weeks was his flight engineer. His father was African and his mother was English. Despite Ron’s reaction to his Luton billet he was happy to work with Fred and the two became great friends. Fred had survived a fire and crash with another pilot in a Catalina. His parachute had the release pins blown out so Fred couldn’t pull the pin to get it to open. Luckily for him the small ‘chute did open and pulled the big one with it and he survived. Fred refused to sit up front if the weather was ‘duff’. He’d retire to the back of the plane because he didn’t want to see himself die. Fred and Ron remained friends after the war and socialised together until Ron emigrated to Australia to be with his grandchildren, he died in 1999 aged 87. As an additional insight into the local war time experience for people of African descent, Ron’s daughter Caroline Gaden has given permission to quote her mother’s own observations: "I think initially there was very much a city v country divide ... rural folk had far less likelihood of meeting migrants from other countries, I'm sure for city folk it was far more common and I do wonder if the war actually helped break down some of the barriers ... everyone was in it together and bombs did not discriminate. I would think that the more industrialised areas in cities with cotton and woollen mills, armament and aeroplane factories and other 'war needed' vehicles would have much greater integration ... but did they socialise or did they head their separate ways after work ... I really don't know. But everyone shared the fear and food and sing-songs as bombs rained down." Caroline herself adds: "…re your father (Fred Weeks) selling the agricultural machinery... I think farmers are a canny lot, they would have been concentrating on what the equipment could do for them. In addition the war did do a lot to break down barriers.... some people put them straight back up post-war but many recognised the contribution made by others... there was probably more antagonism (for want of a better word) or less trust directed towards people who had lined their own pockets during the war or who had found a cushy job away from the bombs and bullets. People who served, of all shapes, sizes, creeds and colours were recognised for their service and given the respect and trust they had earned. Thank you to Richard Weeks and Caroline Gaden for sharing their memories.

0 Comments

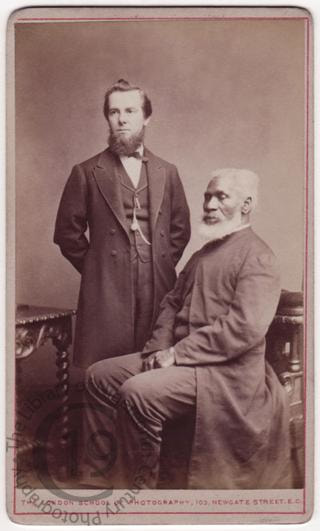

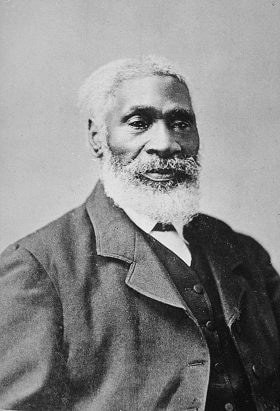

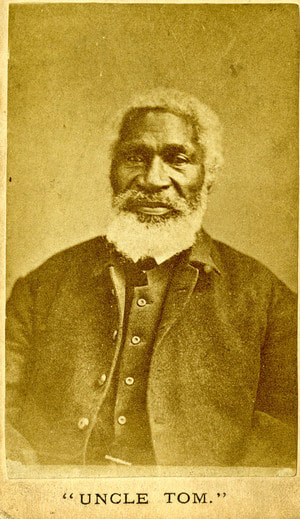

We're always delighted to receive correspondence from people who connect with particular stories and are inspired to investigate further or offer additions. Some of these exchanges remind us of the project's wide reach thanks to this website. Hannah-Rose Murray had previously written about the abolitionists who came to Hull and East Yorkshire for this project and it was the story of Josiah Henson that compelled her to contact us again some weeks ago. Our first story about Henson started for us with a photograph in Hull Museums Collection (Wilberforce House) and Hannah has been kind enough to supply the following extended blog post about him. "My Name is Not Uncle Tom!" Josiah Henson in Britain 1876-1877 In early March, an American colleague sent me a blog post on the African Stories website about Josiah Henson. The post was sparked by an incredible and previously unseen image which had been discovered by the project team in Hull: staring straight into the camera, the now-identified Henson consciously challenges the racist caption of 'Uncle Tom' underneath. In this image, and in life, Henson simultaneously exploited and fought against this symbol of white supremacy, and on several occasions entirely denounced what had become his nickname in Great Britain.

Henson visited Great Britain at least twice, first arriving in 1851. He was the only Black person to exhibit something at the Great Exhibition (wooden boards from his community in Canada) and this excerpt from his autobiography describes the experience in his own words: "At the Exhibition, because my boards happened to be carried over in the American ship, the superintendent of the American Department, insisted that my lumber should be exhibited in the American department. To this I objected. I was a citizen of Canada, and my boards were from Canada, and there was an apartment of the building appropriated to Canadian products. I therefore insisted that my boards should be removed from the American, to the Canadian Department. But the American said "You cannot do it. All these things are under my control. You can exhibit what belongs to you if you please, but not a single thing here must be moved an inch without my consent." I thought his position was rather absurd, but how to move him or my boards seemed just then beyond my control. Josiah Henson's third visit in 1876 sparked international fanfare and celebrity. In order to alleviate debt on his property, Henson sought out reformers and old abolitionist friends in Britain to help him raise money to overcome these financial difficulties. As a result of his famous association with Stowe's novel, he received over two thousand invitations to speak. He was a powerful orator, and newspaper correspondents praised his impressive stage presence. Most of the press paragraphs discussing him were reprinted almost verbatim from London to Liverpool, describing how Henson (the "original" Uncle Tom) "pictured [slavery] in a very effective way." In Sheffield for example, Henson gave two lectures in one day to thrilled audiences, and crowds of people turned up an hour and a half early. At another meeting, hundreds of people were turned away as there was not even standing room left to hear him speak, and his revised edition of his autobiography sold hundreds of copies. According to his white benefactor and editor John Lobb, Henson addressed over 500,000 people all over the country in less than a year. This was an incredible feat, as he was in his late 80s at this point. Although Henson was a successful author in his own right (the first edition of his narrative sold over two thousand copies in 1849, and over six thousand in the first three years before Stowe's novel was published) it was undoubtedly his association with the novel that prompted an invitation to meet Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle in 1877. Henson presented her with a copy of his autobiography and in return received the Queen's portrait. She then asked Henson and John Lobb to sign their names in an album in the castle. They toured the grounds and the state apartments, and left after roughly three hours. [1] Henson's Relationship with 'Uncle Tom' In order to achieve success on the British stage, Henson exploited his association with Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. His books were marketed as the story of "Uncle Tom" and hundreds of articles across the country addressed him as 'Tom' rather than Josiah Henson. This connection – and ultimately racist phrase – began to grate on Henson, and in several meetings across the country denounced he was Uncle Tom. In one meeting in Glasgow, he said: "Now allow me to say that my name is not Tom, and never was Tom, and that I do not want to have any other name inserted in the newspapers for me than my own. My name is Josiah Henson, always was, and always will be. I never change my colours." [2] While Henson's efforts would never be enough to change Victorian racism, he made an extraordinary impact on British society in general. Instead of focusing on the 'Uncle Tom' connection, we should remember Henson's activism, expressed fully in these quotes: "I look back from whence I came, and see by the eyes of my mind what you cannot see with your eyes, because you have not been there, and feel in my heart what you cannot feel, and I hope never will feel, and no one can feel it but the man who has had the iron through his own soul." [3] "[The Archbishop of Canterbury] expressed the strongest interest in me, and after about a half-hours conversation, he inquired, 'At what University sir, did you graduate?" "I graduated, your Grace' said I, in reply, 'at the University of Adversity." [4] Footnotes

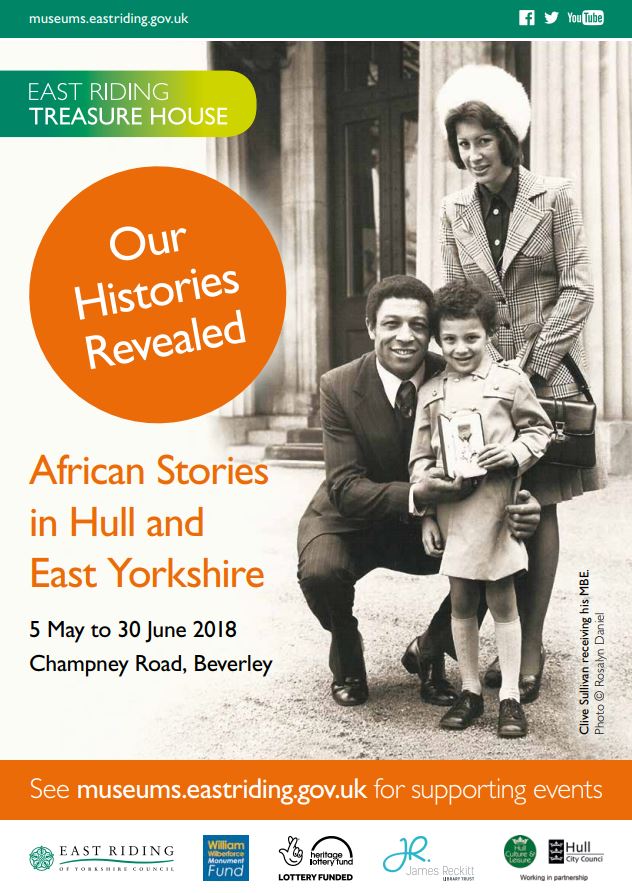

This Saturday (5 May) we open our second exhibition at Beverley's East Riding Treasure House which runs until Saturday 30 June.

After the tremendous success of last year's exhibition in Hull, our latest opportunity to showcase the projects findings will have a greater focus on the people of African descent who visited, lived or worked in East Yorkshire between 1750 and 2007. We have a mix of our most popular releases from last year as well as some newer stories on display. Additionally, to complement the exhibition, we have a free study pack which can be collected from the Treasure House during your visit. The exhibition will feature amongst others the Black servicemen who were based in Cottingham, Filey and Pocklington during the Second World War, the activists and abolitionists who came to the East Riding to speak out against slavery and to campaign for equality and the accomplishments of Black actors, entertainers, sportsmen and entrepreneurs in our area. During the exhibition period, we're hosting three events which include:

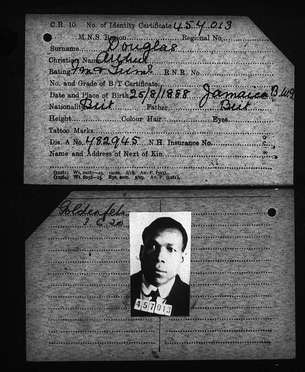

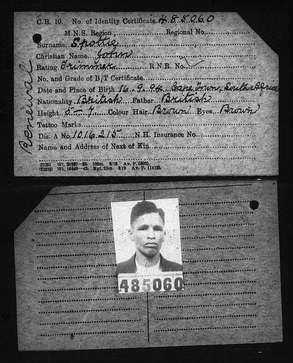

Head to the Events page for more details or if you would like to book a place at one of these events. Through various stories and blog posts our project has uncovered both the turbulent and triumphant history of sailors of African descent in Hull and East Yorkshire. We have explored the lives of individual seaman, themes such as economic hardship, racism, suicide and crime alongside larger stories on the history of sailors with Black heritage in our region. However, we are still finding new material which uncovers more information about the seamen of African descent who visited, lived and worked in Hull and East Yorkshire. This blog post focuses on the dangers of working in the maritime sphere and reveals the names of men who tragically perished. The most common cause of death for seaman was drowning. During the First and Second War many sailors drowned after their vessels were sunk by enemy fire. These included seamen with Black heritage who had a connection to our region, such as Adolphus Meheux, Jim Bailey and William George Ash who are all featured in this project. However, during peacetime one of the biggest determining factors of a safe voyage was the weather. On 10 February 1871, the Great Gale, which was a severe storm in the North Sea, struck the East coast of northern England. When the storm hit, vessels near Bridlington found themselves in desperate trouble and many were wrecked. Around 50 men, at least one of whom was believed to be of African descent, lost their lives because of the Great Gale. A witness recorded “One body being that of the coloured man who escaped from the brig that struck near to the end of… [Bridlington] pier and whose splendid swimming would have saved him but he was disabled by breaking his leg in some way, and the poor fellow was thus compelled to succumb to the waves through which he had battled so bravely, and sank close to the north side of the pier.” Sadly, very few of the sailor’s bodies were identified thus we have not been able to trace this man’s identity. Bad weather was extremely dangerous and posed a threat to the safety of all sailors. Half a century after the Great Gale, tempestuous weather claimed the life of another seaman of African descent. On 25 October 1921, the steam trawler Gamecock arrived back in Hull with the news that their boatswain Ernie Jones, who lived at 76 Campbell Street, had been washed overboard during a terrible storm. [1] More recently, Adam Ali lost his life on board the Kingston Peridot after the vessel encountered bad weather and sank in late January 1968 (read the Ali's family story). As well as drowning at sea, the bodies of sailors were also found in local docks. How they ended up falling into the water in many cases remains a mystery. It is possible that some of the sailors had fallen from the dockside or from their ships when drunk. However, it is remarkable to consider that despite making their living on board ships, many sailors were not strong swimmers. For example, in January 1912, Harry Williams, a seaman of African descent from the Elswick Hall was found in the Albert Dock basin. He had been reported missing in late December and was identified by his hat which was floating beside his body. A verdict on his death was returned as “Found drowned.” [2] A further example is one of Arthur Douglas, a 52-year-old Jamaican sailor who was pulled from the docks on 12 January 1941. He had been drunk when he was last seen in October and had not returned to his ship. Local police surgeon, Dr Scott stated that his body appeared to have been in the water for around 10 weeks. An inquest into his death also returned a verdict of “Found drowned.” [3] Another tragedy in January 1912 resulted in ‘coloured’ seaman, Frederick Hoford, drowning in the Alexandra Dock when trying to save another sailor of African descent. Joseph Daniels, a coal heaver, of Rose Cottages, Marfleet witnessed the events that unfolded. He met the two sailors who were lost and showed them back to the dock area. When they had identified their ship, Daniels left the men and walked only a few yards when he heard a splash and saw Davis in the water. He threw a rope which Davis caught but Holfod had already jumped into the dock unbeknown to onlookers. It was not until Davis was rescued that it was realised the other man had drowned trying to save his friend. [4] In 1941, the body of another sailor of African descent was fished out of the docks. It was reported that South African seaman, John Spottie, had accidently fallen into King George Dock when he was returning to his ship during a blackout. [5] Although, the predominant cause of death for sailors was drowning, other accidents and tragedies also occurred. For example, in January 1916, two laundrymen, Joshua Macauley and Jonas Williams from Sierra Leone were found dead in the washhouse of the Elizabethville which traded between Hull and the Congo and typically carried an all African crew. [6] They had apparently been suffocated by fumes from a charcoal fire while in King George Dock. [7] An inquest was held in Hull regarding their deaths but more information has yet to be found.

Footnotes

Over the next two weeks we're taking a break from releasing new material. This gives you time to catch up on any stories or blogs you have missed and the project team the opportunity to prepare for our upcoming Our Histories Revealed exhibition at the East Riding Treasure House which will run from 5 May to 30 June 2018. We would also like to remind you that during our exhibition we have organised three events:

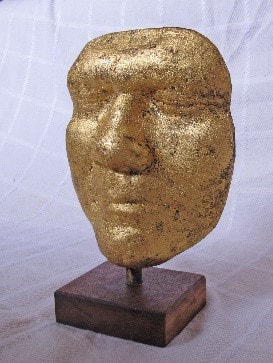

Please contact the East Riding Treasure House in advance if you would like to attend any of the paid events. Richard’s mask We love it when people are inspired by our project to get creative. Richard Weeks has made the cast of his face into a fantastic piece of art. His original alongside others will be displayed in the East Riding Treasure House Exhibition if you missed them at the Hull History Centre last year. Dates for your diary

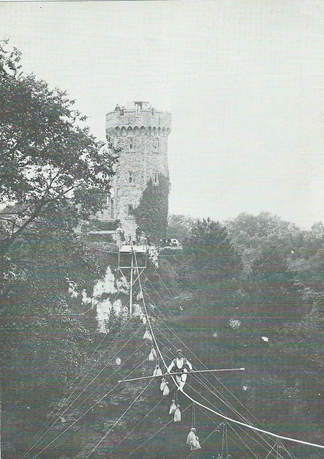

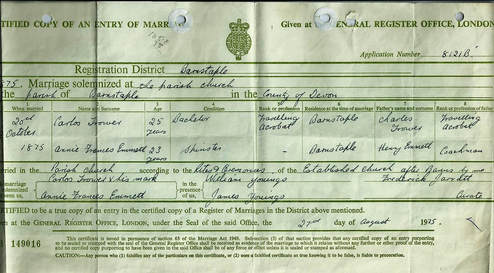

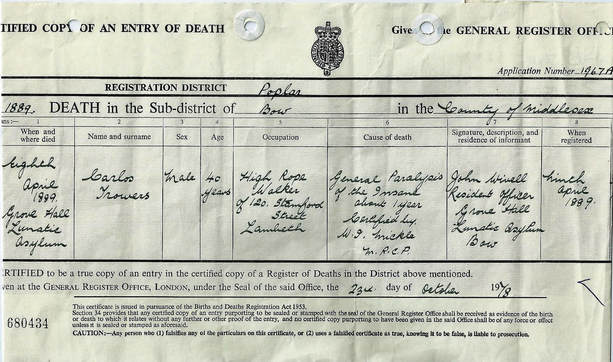

In November 2017 we released a story about Carlos Trower and his performances in Hull and East Yorkshire. As a result, last month we were contacted by Ron Howard, who has been trying to retrace his family tree and find out more about the men who used the show name ‘The African Blondin.’ In our original piece (which can be read here) we alluded to the difficulty of tracing the life of the famous tightrope walker as there appeared to be more than one Carlos Trower and thus more than one African Blondin. Below is Ron’s account of the nineteenth century legend who remains an enigma and his struggles in finding out about his Great Grandfather. Was Carlos Trower the only African Blondin or were there two or three relatives sharing a similar name clouding my research? My Great Grandfather Carlos L. Trower who married Annie Frances Emmett in Barnstaple Devon in 1875 is the focus of my narrative. [1] My interest in Family History began on the death of my Grandmother Gyneeta Caledonia Howard nee Trower in 1968. Her possessions included a framed picture of a slight man of African descent on a tightrope, the rope was fixed to the wall of a tower. Spectators included an attentive lady, two young girls sitting on the wall and a few watchful men. To complete the picture a wagon stood at the tower entrance. This picture was the catalyst for my lifetime passion to confirm the truth regarding the Carlos story. Frequent visits to the Family Records Centre in London soon showed promising results confirming that my maternal line originated in Speeton, Yorkshire with my Great Grandfather Martin Luther. His father, Martin Collingwood Luther was born in Maryland USA in 1804. My Paternal side including Gyneeta, confirmed that my Great Grandmother Annie Frances Emmett married Carlos in the Barnstaple Parish Church in 1875. Carlos was a 25-year-old bachelor who was working as a travelling acrobat. It is likely that he had learned his skills from his father Charles Trower, who was also a travelling acrobat. Carlos was shown in the 1881 census as being born in New York City in 1850. My correspondence to American Circus organisations offered polite but negative responses. However, my luck changed within a few weeks when I received confirmation from The American Library of Congress that Carlos known as ‘The African Blondin’ died in London in 1889 following a long and painful illness. A new lead that Carlos had a professional name gave me the encouragement to widen my search. I visited the Newspaper Archives in Colindale, North West London. However, this proved to be a fruitless visit. However, I was rewarded when the archives were downloaded on a computer. On searching “African Blondin” I was staggered with the final count, over the next three days I copied each one. When I eventually entered my findings on a PC file called the Carlos Chronicle, it occupied over seventy pages. A Trower family contact gave me yet another source, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle that detailed even more articles of Carlos’s New York City appearances. The internet was to become my main source, hungry for facts I entered my favourite phrase “African Blondin” it mentioned Rosherville Gardens a nineteenth century pleasure garden in Gravesend. Eager to find out more, Rose (my wife) and I visited the Gravesend Local History department the next day. I could not control my excitement when the curator opened a book called “Gravesend in Old Photographs” and turned to page 47 where it showed a photograph of ‘The African Blondin,’ a replica of my Grandmother’s photograph but showing a different of tightrope walker, a midlife well-built Black man in a traditional tightrope pose. My Brooklyn Eagle research was about to add to my excitement. A Joseph Augustus Trower brother (not sure if was a relation or this was a show name) of Carlos Trower managed the Grand Union Celebration of the British West India Islands over many years. [2] Unfortunately my US research has not helped in finding any personal Carlos details other than his Grand Celebration appearances and a proposed performance trip to Connecticut with Joseph. The family research website Ancestry reveals that there was another Carlos L. Trower who married Myra Clay in Longton Staffordshire 1864, yet another tightrope walker, is he my Great Grandfather? Or was my Carlos his son or close relation? In my opinion there were two African Blondin’s sharing performances. Myra was recorded as living at 67 Mill Street, North Myton, Kingston upon Hull with her son Carlos in the 1871 census. Carlos it would appear, was not at the same address. He almost lost his life when falling badly at Beverley in 1868. In great agony he was carried to his lodgings with a broken arm and wrist. However, two months later he was yet again performing in Beverley. An interesting chapter “The African Blondin” in the book “Stanley’s Summer Visit” published 1882 mentions “the abundance of black dull hair the man had no Negro skin, his complexion being a copper yellow and his eyes being soft, brown and luminous like those of a deer” this contradicts an earlier description in an article describing Carlos being “a real Negro.” Does this reveal that there were two African Blondin’s? The African Stories in Hull and East Yorkshire project has demonstrated multiple lion tamers used the same show names so tracing their lives and true identities are difficult (read the story of lion tamers in Hull and East Yorkshire). In conclusion my quest is far from over, I am aware of my limited expert knowledge, but it is beyond doubt that the Carlos who married Annie Frances Emmett was an African Blondin performer and is my Great Grandfather. However, it is still unclear if I am related to the Carlos L. Trower who married Myra Clay and had a son Carlos who lived in Hull. Footnotes

Written by Adrian Burrows and researched by John Rodgers.

Although very much the poor relation for professional sport in Hull, when compared to football and rugby league there have been several professional fixtures played in the region which have featured players of African heritage. These games were played at The Circle, Anlaby Road, a ground now more familiarly known as the KCOM stadium home to Hull City and Hull FC.

Professional cricket was played at the ground between 1899 and 1990 and was used by Yorkshire County Cricket Club as one of its home venues. The county operated a very strict policy of selecting Yorkshire born players and only relaxed the rules to allow cricketers born outside of the county to play in 1992 when Sachin Tendulkar, the 19-year-old Indian test player, became the first overseas player to join the county. A year later, Yorkshire signed Richie Richardson, the then West Indies captain, as an overseas player - but were no longer playing at the Circle at this time.

The second player to appear was Barbados born, Keith Boyce who represented Essex in a 3-day county championship match in August 1971. Boyce played 21 times for the West Indies, touring England in 1973 and 1975 and was part of the successful West Indian side that won the inaugural World Cup in 1975.

One other game of note that was organised by Sir Roy Marshall (read our feature on Roy), the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Hull was between Yorkshire and the touring West Indian cricket team as part of the 1983 events in Hull to mark the 150th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in the British Empire. The game also served as a warm-up for the West Indies ahead of that year’s World Cup held in England. In the event because the proposed Yorkshire side included Geoffrey Boycott and Arnie Sidebottom, two players who had participated in an unauthorised tour of apartheid era South Africa, the West Indies refused to play the game and it had to be cancelled.

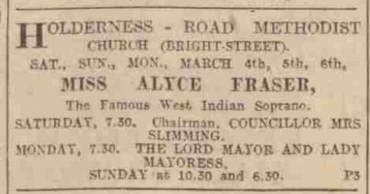

Picture Blog #9: "Uncle Tom" c. 1870-1910 In July 2017 we released a picture blog which focused on the above sepia photograph of a Black gentleman with the caption "Uncle Tom" printed at the bottom (read our original blog post). We sadly concluded that although this image was part of the Hull Museum's collections and handwriting on the back mentioned Hessle Road, the image raised more questions than answers and without knowing more information it would be difficult to conduct additional research. However, last month we were unexpectedly contacted by a lady in America who identified the man as Josiah Henson, who it is believed was the inspiration for the title character of Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1852 novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin. Further research has revealed that Josiah Henson was an African American slave born on 15 June 1789 in Charles Country, Maryland. [1] He had a torturous life enslaved in America and in 1828 tried to buy his freedom, but his master Isaac Riley cheated Henson of this 'privilege' by changing documentation to ensure that the cost was more than the African American could afford. However, in 1830 Henson escaped to Canada his wife Nancy and four children where they regained their freedom. [2] In Canada, Henson founded a settlement and labourer's school for fugitive slaves at Dawn, Kent Country, Upper Canada and became a Methodist preacher. [3] Henson travelled to Britain in 1851 to raise money for the educational institution collecting approximately £1000. [4] Unfortunately, there is no evidence he came to Hull on this visit. In 1876, he travelled to across the Atlantic once again, this time to raise money for the Wilberforce Educational Institute at Chatham, Ontario which opened in 1873 after the Nezrey Institute and British American Institute in the Dawn Settlement had merged. [5] This facility was for the benefit of children of African descent. [6] It was reported in the Hull Packet that at the age of 87 years old, Josiah Henson had arrived in Britain for another visit of the country. [7] Henson travelled extensively giving lectures in London in September and November then Canterbury and Nottingham in December 1876. [8] In January 1877, he spoke to audiences in Loughborough and then Sheffield. [9] Henson went on to give talks in Scotland between February to April he taking a very short break in March to meet the Queen at Windsor Castle. [10] Henson then made his way from Scotland to Liverpool to board the China steam ship on 27 April 1877 to return to Canada. [11] Although the educational facility he was collecting funds for was named after William Wilberforce and he toured Britain extensively, there is no evidence to suggest that Josiah Henson visited Hull or East Yorkshire. Thus, how Hull Museums came to have his photograph remains a mystery. Sadly, Henson died at the age of 93 in Dresden, Ontario on 5 May 1883. His life has been documented in three editions of his autobiography. The first, 'The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself' was published in 1849. [12] Nine years later an extended version of the narrative of his life entitled 'Truth Stranger Than Fiction: Father Henson's Story of His Own Life.' [13] In 1876, after the clamour to know more about his life, Henson published an updated version of his life, Uncle Tom's Story of His Life from 1789 to 1875. [14] Shirley Bassey From the beginning of our project we have been repeatedly informed that Shirley Bassey performed in Hull, Bridlington and Scarborough in the 1950s and 1960s. [15] However, although people have generously come forward and shared their recollections of going to see the world-renowned performer, we have found it difficult to pin point when and where exactly Bassey performed. The only evidence we have found placing her in the East Yorkshire is a newspaper article that featured in The Stage advertising Bassey's performance with Ronnie Aldrich and the Squadronnaires at Scarborough's Flora Hall on 4 June 1960. [16] If you have any information, pictures or promotional material relating to Shirley Bassey in Hull or East Yorkshire please contact us. Holme-on-Spalding Moor Last week we released the story of James Clinton Jordan, an airman in the US Air Force (USAF) based at Holme-on-Spalding Moor. Last year we were notified that African American airmen were stationed in East Yorkshire in the 1950s. They travelled to Hull in their free time and enjoyed the array of entertainments in the city. However, we know very little about them. If you have any information or pictures of African American airmen in Hull and East Yorkshire, please contact us. Footnotes

The fantastic Hull Daily Mail Flashback series has published several pictures which document people of African descent in Hull and East Yorkshire over the decades. We are delighted that we can celebrate the people who are featured and include their presence in our project. Some of the photographs we have come across contain people who have engaged with our project such as the picture below showing David Gambe playing in the Beverley Blue Brass Band with John Jessop, Alan Whittle, Mike Palframan, Pete Barnecutt and Marian Grimes at a parade in 1987. [1] David Gambe is one of the 30 contributors to our Contemporary Voices series of oral histories. Another recent feature has been Clive Sullivan and other friends of Tom Wilson’s at the former Hull City and Goole Town defender’s testimonial fund dinner in 1978. [2] The photo below shows Hull City’s Alex Dyer with Tom Wilson presenting a trophy to Peter Coulson, the captain of the Croxby School football team for winning the Beverley and Haltemprice B league for under 11’s. Sadly, this picture is undated, but it is believed to have been taken when Dyer played for Hull City in the 1980s. [3] Hull City AFC was founded in 1904 but it was not until 1986 that Black footballers became part of the squad. There are other pictures which have featured in the flashback series that we would love to know more about, such as the image below which shows Peter Brough and his dummy Archie meeting ‘war orphans’ in January 1954 at the Regal Cinema, Hull. If you are one of the children or know someone in this photograph, please contact us. We are looking to produce a story on children orphaned during the First and Second World War soon so any information you are willing to share would be greatly appreciated. [4] With thanks to Dr Nicholas Evans for bringing these images to our attention. Footnotes

On the morning of 6 March 1933, Fraser and Gibbon visited Wilberforce House, where they spent hours learning about the local abolitionist. Later they headed to Ferens Art Gallery to look at the collections on display. After this, the women prepared for their final performance in Hull which was attended by the Lord and Lady Mayoress. The church was filled to capacity with many people being turned away because they could not fit in the building. The Hull Daily Mail reported that "a notable feature was the attendance of about a dozen coloured men, some accompanied by their wives and families, and to rounds of applause Miss Fraser made her way to them and gave them a welcome." Gibbon also showed off her musical talents, and after the performances finished both singers and the Lady Mayoress received bouquets to rapturous applause.

Despite the impact that she seems to have made through her performances and her connection with the region's Black History, Alyce Fraser’s time in Hull would have been lost had it not been for three small newspaper articles which featured in the Hull Daily Mail. [2] Footnotes

|

Follow usArchives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed