Records of Black prizefighters have been found in Britain as far back as the eighteenth century.[1] However, currently there is no record of pugilists of African descent in Hull and East Yorkshire until 1902. Despite the lack of published accounts, it is probable that given the relationship between boxing and the maritime sphere, fighting contests took place near the ports in the region throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The fascinating footage of amateur Black prizefighters at Hull Fair below demonstrates that unorganised fights were showcased for entertainment purposes at local events such as travelling fairs. However, as many were undocumented the narrative of Black boxers before the twentieth century has been silent.

|

Henry Gess's Menagerie and Boxing Booth

The striking grainy film to the right records two Black boxers enthusiastically beckoning the crowd at Hull Fair in 1902 to 'have a go' at standing two rounds of bare knuckle boxing. The prize for success of any man (or any woman if the posters in the film are anything to go by) was £5 and the charge for the participants 2d (two old pennies). The man in the white shirt at the start of the short film seen pointing to the 'nobody barred' sign was Henry Gess, who began a travelling Menagerie (an exotic animal show) and boxing booth in the nineteenth century.[2] Boxing booths had been associated with travelling fairs from the early nineteen hundreds until the 1947 Boxing Board of Control brought about their decline through legislation.[3] |

|

|

Boxers and Lion Tamers

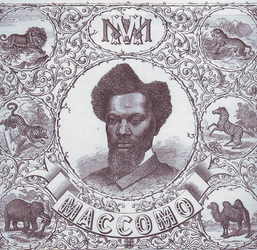

Newspaper reports suggest that Gess's Menagerie had visited Hull Fair in 1897 when, horrifically, one of his lion tamers had been attacked by a lion there.[4] The connection between Gess's lion tamers and the Black boxers who appear in the film is poignant, for it appears that many men who were employed by these travelling Menageries as 'lion tamers' were, like the boxers, also of African descent. A wonderful image of Gess's Black lion tamer standing in front of a lion's cage appears on the Gess/Wilson family history site here. As early as 1869 the Bridlington Free Press was reporting a visit to the area (also Beverley and Driffield) of the famous African lion tamer Martini Maccomo who travelled with Manders Grand National Star Menagerie.[5] Read about the story of lion tamers of African descent who visited and performed in the local area with the travelling Menageries here. |

Fairground Boxing Rings

|

One of the most famous Black British boxers who began his boxing career in the fairground was Manchester-born Len Johnson. Described as a 'coloured' middle-weight, Johnson had toured the country with Harry Furness's Boxing Show, and in 1933 took on the role of boxing referee at a match in Hull.[6] The report in the Hull Daily Mail described an evening of fights at the East Hull Baths, all controlled by Johnson. Johnson, who had had an illustrious career was unfortunately stifled by the 'colour-bar' and therefore refused to be allowed to box for the important Lonsdale belts. He became dissillusioned with the boxing authorites and began his own boxing booth in the same year as he retired and appeared in Hull.[7]

|

Boxing in Hull from 1904

|

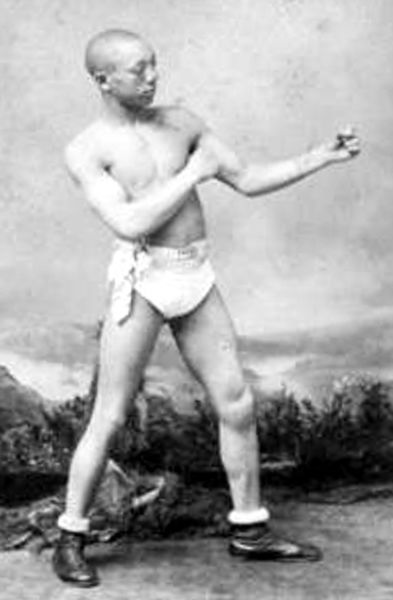

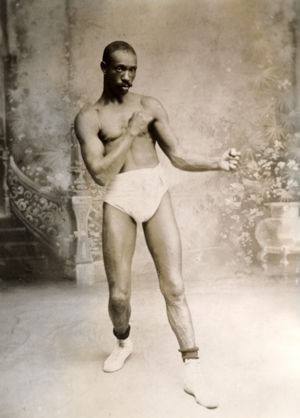

The first professional fighter of African descent to have entered the ring at a boxing event in Hull was reportedly American featherweight George Dixon, also known as Little Chocolate (right). [8] During his tour of England, he attended a competition entitled an 'Assault-at-Arms’ at the Boulevard stadium in 1904. This event was organised to promote boxing as a sport in Hull and promised a lucrative prize fund for the winner. Promotion for the event attracted mainly seasoned fighters like Dixon, who fought at least 147 times in Britain and America during his career.

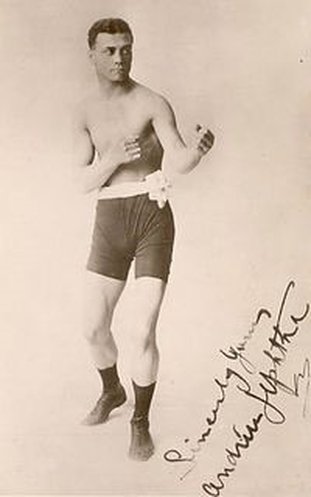

Although boxing events were organised on a regular basis in Hull and East Yorkshire during the first decade of the twentieth century, there is sparse evidence to suggest that Black professionals played a significant role in lucrative prizewinning competitions. However, in October 1909, several members of the boxing fraternity travelled to Withernsea to complete a training programme. One of the athletes was ‘coloured’ South African boxer, Andrew Jephtha (Jeptha) who was dubbed by the Hull Daily Mail as the ‘welter-weight champion of the division.’[9] Unfortunately, very little is known about the facilities that were used to train the cohort, where exactly they were based or how long they stayed at the seaside resort. [10] Despite training in East Yorkshire, Jephtha never fought in the region. He was scheduled to fight Tom Stokes from Mexborough in Hull six months prior to his arrival at Withernsea. However, the boxer from Yorkshire declined the fight and a purse of £75 put up by the Hull Syndicate.[11] The reason behind Stokes’ decision remains unknown. However, it was not uncommon for white boxers to dismiss matches against Black fighters.

|

|

As the sport started to be further celebrated for its entertainment value, boxing events began to take place weekly across the region which attracted larger crowds. The higher volume of organised fights and the strive to arrange the best contests ensured that a greater number of Black boxers travelled to the area. The respect given to pugilists of African descent can be demonstrated by their position on the boxing card and the praise given to them after contests had ended. An example of this occured on 4 December 1909, when the New Olympic Gymnasium was opened on Mason Street Hull. The occasion was marked with a twelve-round fight between Black boxer Young Jady from Liverpool, and Young Norton from Yorkshire.[12] Although Jady lost the match, the Hull Daily Mail reported that the Black fighter had made a good account of himself.[13] Jady later returned to Hull on 13 January 1910 to fight Driver Hicks at the Olympic Gymnasium. In the same year, professional Black fighters from across the Atlantic also appeared in Hull. For example, Frank Inglis from St Lucia featured in the region on 7 March 1910.[14] He fought Jerry Thompson from Grimsby at Hull City Athletic Club in front of a large crowd. Their scheduled fifteen-round contest was advertised as the premier event, despite the West Indian being in the latter stages of his career.[15] Another relatively well-known Black boxer fought in Hull in July 1910, when Bobby Dobbs from Cartersville, Georgia fought Harry Rowe from Hartlepool at the New Olympic Club.[16] Dobbs travelled across Britain, America and Europe for 196 fights over two decades - the majority of which he won. Thus, for fighters of African descent who had risen to the top of their class, boxing, which was traditionally perceived as a white working-class sport, enabled them to travel and challenge social stigmas.

|

|

The success of amateur and professional boxers of African descent was publicised in local and national newspapers throughout Britain in the early twentieth century. This caused a major problem in Britain and even more so in America. By excelling in the boxing arena, Black fighters threatened the social and racial hierarchy that had been ingrained into the British mindset for over three centuries. Firstly, the notion that Black people were physically inferior to their white counterparts was completely undermined as pugilists of African descent showed their physical prowess and knowledge of boxing in the ring. Furthermore, the ability of Black fighters to challenge a white opponent and win raised anxiety about the security and ‘wellbeing’ of the Empire.[17] In effect it was believed that if White men were beaten it would send out a message that they could be challenged in various Imperial outposts. Thus, it was thought boxing would become a symbol for an uprising against colonial governance. These concerns became more intense in 1911 as African American, Jack Johnson became a celebrity in the boxing world. He had won the heavyweight title against Tommy Burns in Sydney in 1908 and subsequently a contest was proposed with Billy Wells in the winter of 1911. The fight was eventually declared illegal and a colour-bar was imposed on the sport which prevented boxers of African descent fighting in high profile matches.

|

The colour-bar, however did not stop Black boxers participating in prize fights or amateur contests. Thus, pugilists of African descent could still be seen by local audiences in Hull and East Yorkshire after 1911. On 25 November 1912, the Hull City Athletic club was used for a much-anticipated fight between Tommy Stokes and Jim Heathcote. Their undercard contained, a ten-round contest between Ernest Robinson from Bridlington and Boney Ormond who was described by the Hull Daily Mail as the ‘coloured boxer of Hull.’[18] Unfortunately, Ormond was disqualified for low blows which he advised were unintentional. However, he does not appear to have fought again and sadly, no further records about his life can be found.

Although, the colour-bar did not completely prevent Black boxers from fighting in local competitions, there was a discernible shift in reporting that boxers of African descent would feature in the ring. Between 1912 and the early 1920s very few articles in local newspapers referred to the presence of Black fighters in the region. However, in 1922 they did participate in organised matches at Wenlock Barracks in Hull. On 26 June 1922, one of the main attractions at this venue was a fight between Alf Carmichael and Black boxer, Alf Stewart (Steward) both from Hull. The contest ended when Carmichael was disqualified for using his elbow and fouled several times.[19] Unfortunately, no further information about Steward has been found. Around the same time Paddy Slattery, a boxer of African descent residing in Liverpool travelled to the city to fight Harry Moody from Hull. He also fought Young Pearce another local fighter at Wenlock Barracks a month later. Pearce was disqualified for holding. However, the Hull Daily Mail suggested to its readers that it was not a fair contest as the Black boxer had a height and weight advantage.[20]

Although, the colour-bar did not completely prevent Black boxers from fighting in local competitions, there was a discernible shift in reporting that boxers of African descent would feature in the ring. Between 1912 and the early 1920s very few articles in local newspapers referred to the presence of Black fighters in the region. However, in 1922 they did participate in organised matches at Wenlock Barracks in Hull. On 26 June 1922, one of the main attractions at this venue was a fight between Alf Carmichael and Black boxer, Alf Stewart (Steward) both from Hull. The contest ended when Carmichael was disqualified for using his elbow and fouled several times.[19] Unfortunately, no further information about Steward has been found. Around the same time Paddy Slattery, a boxer of African descent residing in Liverpool travelled to the city to fight Harry Moody from Hull. He also fought Young Pearce another local fighter at Wenlock Barracks a month later. Pearce was disqualified for holding. However, the Hull Daily Mail suggested to its readers that it was not a fair contest as the Black boxer had a height and weight advantage.[20]

|

Despite the inclusion of boxers of African descent in local contests, the precedent set by the Johnson and Wells fight in 1911 was reinforced in the early 1920s when a match was proposed in Jersey between Battling Siki and George Carpentier.[21] Thus, for over more than a decade, professional Black fighters were denied the opportunity to demonstrate their potential in the ring at the highest level. In the early 1930s the situation did start to change as campaigners and promoters tried to ban the colour- bar from the sport. This coincided with local newspapers in Hull and East Yorkshire reporting a greater number of boxers of African descent in the region. For example, in early March 1930, the Hull Daily Mail reported that Black boxer Billy Hill from Manchester was beaten by Herbert Curry in the city.[22] That winter Mr Gould, a former amateur boxer from Hull advertised a boxing bill at Fulford Hall on Beverley Road which included Black fighters such as African Kid, from Newcastle and Choc (Kid) Melgram from Otley.[23] Around the same time Melgram travelled to Goole to fight Tubber Burrell of Leeds. The contest resulted in a draw and a further match between the pair took place in Hull in November 1931. [24] Three years later, Melgram fought at the Assembly Rooms in Beverley. This was the last time he visited Hull and East Yorkshire.

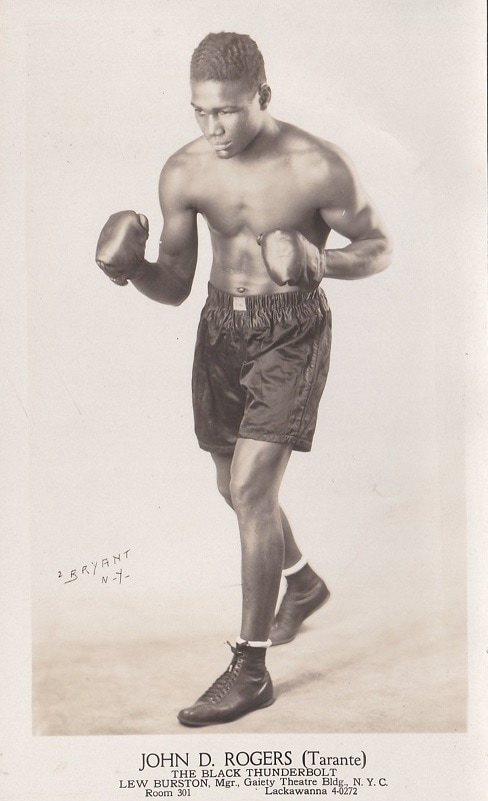

Throughout the 1930s Black boxers featured at various venues in Hull as the sport thrived in the city. In December 1931, the Assembly Rooms held the N.C. welter-weight and N.C. light-heavy-weight competitions alongside other less prestigious fights. One of these featured Black pugilist, Chick Benson from Liverpool, who fought E. Rooms from Hull Boys’ Club.[25] Regular boxing events were also organised at the Madeley-Street Baths where a match was fought between famous Black boxer, Jimmy Tarante also known as Kid Rogers and Canadian Del Fontain, much to the delight of spectators. |

While contests predominantly took place in Hull, there is evidence to suggest Black fighters also featured in events that were organised in East Yorkshire including Beverley, Scarborough and Bridlington. For example, spectators who visited the Assembly Rooms in Beverley in May 1933 witnessed a night of boxing which included Sam Minto, a boxer with African heritage from London.[26] Darkie Ellis fought at Scarborough and Hull several times in the early 1930s and in July 1935, a fight was arranged between the Black boxer and Bob Simpkins in Bridlington.[27] Unfortunately, it has not been possible to confirm if the fight went ahead. However, a year prior, Eddie Kid Larty, a featherweight champion of the Gold Coast did fight at the seaside resort.[28]

Although, the 1930s witnessed a higher volume of professional Black boxers in the sport and a relaxing of the colour-bar they were not able to challenge for a British title until 1948.[29] After this date fighters of African descent have featured heavily as champions in the sport. Famous men who have fought in Hull and East Yorkshire more recently include Johnny Nelson and Lennox Lewis. On 18 March 1986, cruiserweight Nelson began his career at the Westfield Country Club in Cottingham. He lost his fight with Peter Brown on points and did not return to fight in the region during his career. Three years later, on 10 October 1989, a young Lennox Lewis fought Steve Garber at Hull City Hall. This was only his fourth professional fight.

Although, the 1930s witnessed a higher volume of professional Black boxers in the sport and a relaxing of the colour-bar they were not able to challenge for a British title until 1948.[29] After this date fighters of African descent have featured heavily as champions in the sport. Famous men who have fought in Hull and East Yorkshire more recently include Johnny Nelson and Lennox Lewis. On 18 March 1986, cruiserweight Nelson began his career at the Westfield Country Club in Cottingham. He lost his fight with Peter Brown on points and did not return to fight in the region during his career. Three years later, on 10 October 1989, a young Lennox Lewis fought Steve Garber at Hull City Hall. This was only his fourth professional fight.

Boxers of African Descent from Hull and East Yorkshire

While many boxers of African descent visited Hull and East Yorkshire, we have only been able to identify a small number of those who lived in the region. The earliest and best documented was flyweight Charlie Cooper. His debut fight took place on 5 June 1915 in Hull. However, there is limited information about his career until early January 1920, when he fought local boxer Young O’Connor and lost.[30] Two months later, Cooper was beaten by Young Lewis in Manchester.[31] In February 1921, spectators at the Madeley-Street Baths witnessed Cooper get beat once again during a lengthy programme of boxing sponsored by the Earles’ Boilershop Shipyard and Engine Works Distress and Fresh Air Fund. A year later, on 1 May 1922, the Black boxer attended a fight night at the Londesborough-Street Barracks. He fought Johnny O’Connor in a scheduled 15-round encounter, which only lasted 5 before the referee stopped the fight as Cooper was rendered defenceless. [32] His last fight was against Jack Burrell at Fenton Street Barracks in Hull. During his career, Cooper won only three out of eight known contests. However, despite his poor record, there is some evidence to suggest that he was accepted into the boxing community and was well known in Hull. Reports on his first fight suggested he was from Guiana, however, subsequent articles in the 1920s commented that he was a local man from Hull. Sadly, after his last recorded fight, Cooper slipped into poverty and in January 1922 was charged with leaving his ‘white wife and two children’ at their home in Courtney-Street, after they became chargeable to the Sculcoates Guardians. It appears to have been a misunderstanding as Cooper explained he had gone to Grimsby to find a ship. Why he stopped boxing remains unclear, however it may have been due to physical health as he advised officers that he made more money from boxing than sailing.[33] However, there are no records of him fighting again.

|

It was not until the 1930s that another Black boxer from the region was recognised in the media. Bob Ryan, labelled as the ‘coloured’ fighter from Hull fought in various venues across the region. They included the Assembly Rooms in Beverley and Arcadia in Scarborough. He also competed in matches across North Yorkshire and North-East England. [34] Ryan’s boxing record was very poor, winning only five out of twenty known fights. Unfortunately, it has proven difficult to ascertain where in Hull he lived or whether he had any family in the region. Another boxer of African descent who lived in Hull around the same time as Ryan was Frederick David Thomas Emanuel Harold. No details about his career have been found. However, on 13 June 1936, the Hull Daily Mail reported that a Black boxer and tap-dancer of the same name from Hull was charged at Lincoln Police Court for stealing jewellery valued at around £75 from the Crown and Anchor Hotel.[35] As of yet no further records have been found about this intriguing character.

More recently in 2006, Curtis Woodhouse (right), who was born in Beverley, retired from football and became a professional boxer. Although, he did not fight in the region until 2009, he has resided in East Yorkshire for many years.

|

Can you help provide more information about Black boxers in Hull and East Yorkshire?

Due to the unavailability of personal records and the lack of digitised resources after 1939 it is difficult to retrace fighters of African descent in the region. If you know any other Black male of female boxers who lived, trained or fought in Hull or/and East Yorkshire between 1750 and 2007 please click here to contact us.

Due to the unavailability of personal records and the lack of digitised resources after 1939 it is difficult to retrace fighters of African descent in the region. If you know any other Black male of female boxers who lived, trained or fought in Hull or/and East Yorkshire between 1750 and 2007 please click here to contact us.

Footnotes

[1] Kevin R. Smith, Black Genesis: The History of the Black Prizefighter, 1760-1870 (Lincoln: iUniversity, 2003).

[2] For more on the Gess family see: http://www.wilson-history.co.uk/html/gess_family.html

[3] https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/nfca/researchandarticles/fairgroundshow

[4] Hull Daily Mail, 13 October, 1897, p. 3.

[5] Bridlington Free Press, 16 October, 1869, p. 1.

[6] Hull Daily Mail, 19 December, 1933, p. 11.

[7] http://www.blackpresence.co.uk/len-johnson-black-british-boxer/

[8] Hull Daily Mail, 2 March 1904, p.5 and 14 March 1904, p. 5

[9] Hull Daily Mail, 15 October, 1909, p. 6.

[10] Hull Daily Mail, 20 October, 1909, p. 8.

[11] Hull Daily Mail, 24 March, 1909, p. 6.

[12] Hull Daily Mail, 30 November 1909, p. 5

[13] Hull Daily Mail, 7 December 1909, p. 8.

[14] Hull Daily Mail, 4 March 1910, p. 6.

[15] Hull Daily Mail, 4 March 1910, p. 6.

[16] Hull Daily Mail, 8 April 1949, p. 6.

[17] Neil Carter, British Boxings Colour-Bar, unpublished document.

[18] Hull Daily Mail, 26 November 1912, p. 5.

[19] Hull Daily Mail, 27 June 1922, p. 2.

[20] Hull Daily Mail, 26 August 1922, p. 3.

[21] Neil Carter, British Boxings Colour-Bar, unpublished document.

[22] Hull Daily Mail, 3 March 1931, p. 9.

[23] Hull Daily Mail, 18 November 1930, p. 9 and 20 November 1930, p. 11.

[24] Hull Daily Mail, 13 November 1931, p. 9

[25] Hull Daily Mail, 2 December 1931, p. 9.

[26] Hull Daily Mail, 20 May 1933, p. 5.

[27] Hull Daily Mail, 4 July 1935, p. 15.

[28] Hull Daily Mail, 25 October 1949, p. 6.

[29] P. Ismond, Black and Asian Athletes in British Sport and Society: A sporting chance (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2003), p. 27

[30] Hull Daily Mail, 15 January 1920, p. 3.

[31] Hull Daily Mail, 10 March 1920, p. 5.

[32] Hull Daily Mail, 22 May 1922, p. 6.

[33] Hull Daily Mail, 28 January 1922, p. 4.

[34] Hull Daily Mail, 3 December 1934, p. 7.

[35] Hull Daily Mail, 15 June 1936, p. 8.

[1] Kevin R. Smith, Black Genesis: The History of the Black Prizefighter, 1760-1870 (Lincoln: iUniversity, 2003).

[2] For more on the Gess family see: http://www.wilson-history.co.uk/html/gess_family.html

[3] https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/nfca/researchandarticles/fairgroundshow

[4] Hull Daily Mail, 13 October, 1897, p. 3.

[5] Bridlington Free Press, 16 October, 1869, p. 1.

[6] Hull Daily Mail, 19 December, 1933, p. 11.

[7] http://www.blackpresence.co.uk/len-johnson-black-british-boxer/

[8] Hull Daily Mail, 2 March 1904, p.5 and 14 March 1904, p. 5

[9] Hull Daily Mail, 15 October, 1909, p. 6.

[10] Hull Daily Mail, 20 October, 1909, p. 8.

[11] Hull Daily Mail, 24 March, 1909, p. 6.

[12] Hull Daily Mail, 30 November 1909, p. 5

[13] Hull Daily Mail, 7 December 1909, p. 8.

[14] Hull Daily Mail, 4 March 1910, p. 6.

[15] Hull Daily Mail, 4 March 1910, p. 6.

[16] Hull Daily Mail, 8 April 1949, p. 6.

[17] Neil Carter, British Boxings Colour-Bar, unpublished document.

[18] Hull Daily Mail, 26 November 1912, p. 5.

[19] Hull Daily Mail, 27 June 1922, p. 2.

[20] Hull Daily Mail, 26 August 1922, p. 3.

[21] Neil Carter, British Boxings Colour-Bar, unpublished document.

[22] Hull Daily Mail, 3 March 1931, p. 9.

[23] Hull Daily Mail, 18 November 1930, p. 9 and 20 November 1930, p. 11.

[24] Hull Daily Mail, 13 November 1931, p. 9

[25] Hull Daily Mail, 2 December 1931, p. 9.

[26] Hull Daily Mail, 20 May 1933, p. 5.

[27] Hull Daily Mail, 4 July 1935, p. 15.

[28] Hull Daily Mail, 25 October 1949, p. 6.

[29] P. Ismond, Black and Asian Athletes in British Sport and Society: A sporting chance (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2003), p. 27

[30] Hull Daily Mail, 15 January 1920, p. 3.

[31] Hull Daily Mail, 10 March 1920, p. 5.

[32] Hull Daily Mail, 22 May 1922, p. 6.

[33] Hull Daily Mail, 28 January 1922, p. 4.

[34] Hull Daily Mail, 3 December 1934, p. 7.

[35] Hull Daily Mail, 15 June 1936, p. 8.