British Black Presence from the Roman Period to the

Present Day and the new GCSE 'Migration in Britain' Module

By Martin Spafford

Part Four: Africans in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Britain

Africans in nineteenth-century Industrial Britain

|

“Among the crowd all specimens of man, Through all the colours which the sun bestows, And every character of form and face: The Swede, the Russian; from the genial south The Frenchman and the Spaniard; from remote America, the Hunter-Indian; Moors,Malays, Lascars, the Tartar, the Chinese, And Negro Ladies in white muslin gowns.” |

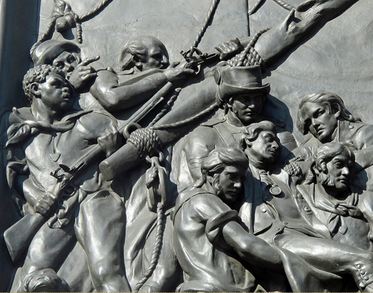

This was the year of the Battle of Trafalgar, and if you look closely at the relief of Nelson’s death at the base of his column in Trafalgar Square, on the side facing down Whitehall, you will see the armed Black sailor a few feet from the dying admiral.

|

A few years later, an 1818 cartoon by Cruikshank (below) commenting on traffic chaos in Piccadilly has a Black man (possibly a baker) and boy among the crowd. One of Cruikshank’s 1820 illustrations to a book called Life in London by Pierce Egan, has a Black man dancing with a White woman in the All Max pub. This is Egan’s description of the pub:

“Every cove that put in an appearance was quite welcome, colour or country considered no obstacle…Lascars, blacks, jack-tars, coal-heavers, dustmen, women of colour, old and young, and a sprinkling of the remnants of once fine girls, and all jigging together.” |

|

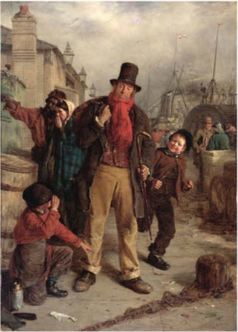

The Black presence in industrial Britain is everywhere if you care to look. Erskine Nicol’s 1871 painting of an Irish immigrant, Jim Blake, arriving in Liverpool, shows a Black sailor helping another arrival, a young woman, find her way. This man may have been one of the thousands of migrant seamen who worked on the merchant ships exporting coal and bringing goods from Asia and the Americas to the port cities and settling there, often marrying local women and establishing our first modern multicultural working-class communities in Cardiff, Liverpool, Glasgow, Liverpool, Newcastle, South Shields and Hull. |

Africans and African Caribbeans in Early Twentieth-Century Britain

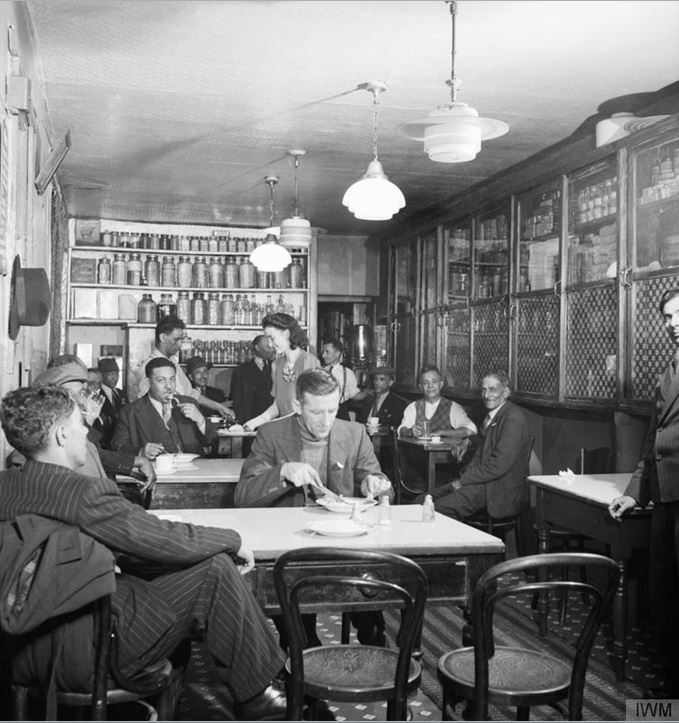

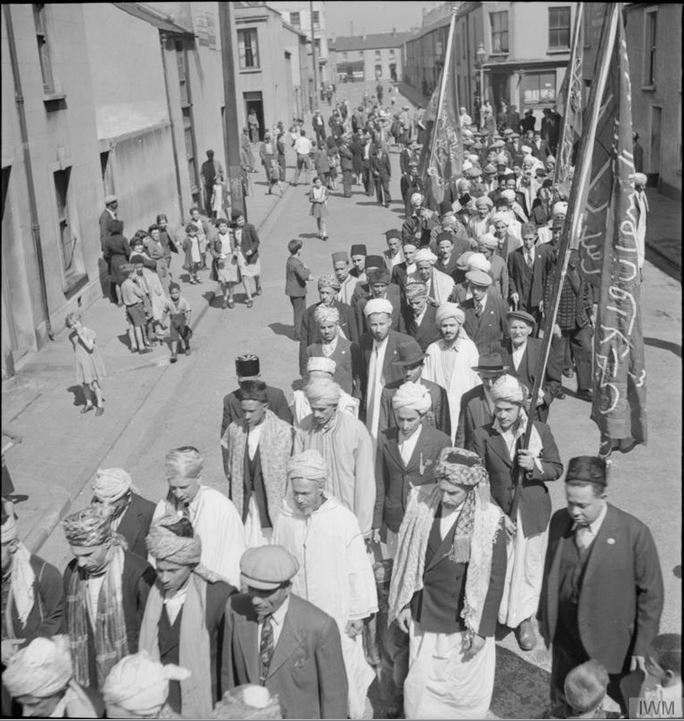

In the two World Wars ‘coloured seamen’ from Africa, Asia and the Caribbean formed between a third and a half of the crews on the Atlantic convoys without whom Britain could not have survived. A wonderful series of the Imperial War Museum’s photographs of the diverse community of Butetown, Cardiff in the 1940s can be found online at http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/search?query=cardiff++muslims+1943&items_per_page=10

Stories of Black British people during the wars can be found in Stephen Bourne’s books Black Poppies and Mother Country. In the Second World War these include Christopher, Joan and Joseph Cozier, children evacuated from East London; fireman Fernando Henriques from Jamaica; dancer and bandleader Ken ‘Snakehips’ Johnson; and singer Adelaide Hall. When the MV Empire Windrush docked in 1948 one of the passengers was saxophonist Mona Baptiste, one of several Caribbean women on board.

Below is a fascinating 1944 propaganda film by the Colonial Film Unit called ‘Springtime in an English village’ which shows a Black girl being crowned Queen of the May in a Northampton village (look from 1.53 mins in).

One of the comments below the clip on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6QbHhm4620I says:

“I met the girl featured in this film today, in the doctor's office. Her name is Stephanie. She and her nonidentical twin sister, Connie, were both in this film; Stephanie was the one crowned Queen of the May. She is the daughter of a Nigerian man and an Irish woman. She said that at the time they lived in London, only three Black families lived there. I asked her whether there had been perceptible racism in London at that time; she said it was there (imagine the word there is underlined) but not obvious. She and her sisters and brother were indeed evacuees, as an earlier commentator posited; they were sent to the country when she was eight. She said there were no other Black families in that town. Though this was a propaganda film, from what I gathered, the children in her class had actually chosen her Queen of the May, and she was the first Black Queen of the May in England; this perhaps prompted the reenactment shown in the film... In 1958 Stephanie moved from London to Alabama with her American husband, who she met during the war. She had at least two children, and currently lives in Maryland. In her face, you can still see the face of the little girl in the film.”

“I met the girl featured in this film today, in the doctor's office. Her name is Stephanie. She and her nonidentical twin sister, Connie, were both in this film; Stephanie was the one crowned Queen of the May. She is the daughter of a Nigerian man and an Irish woman. She said that at the time they lived in London, only three Black families lived there. I asked her whether there had been perceptible racism in London at that time; she said it was there (imagine the word there is underlined) but not obvious. She and her sisters and brother were indeed evacuees, as an earlier commentator posited; they were sent to the country when she was eight. She said there were no other Black families in that town. Though this was a propaganda film, from what I gathered, the children in her class had actually chosen her Queen of the May, and she was the first Black Queen of the May in England; this perhaps prompted the reenactment shown in the film... In 1958 Stephanie moved from London to Alabama with her American husband, who she met during the war. She had at least two children, and currently lives in Maryland. In her face, you can still see the face of the little girl in the film.”

|

A hugely significant part of the experience of Black people in this period was the experience of racism, illustrated starkly by the story of David Oluwale. A Nigerian stowaway on a ship that docked in Hull in 1949, he was a British citizen and therefore not an illegal immigrant. He was, however, charged as a stowaway and sentenced by Hull magistrates to 28 days imprisonment in Leeds. Twenty years later, destitute and homeless, he drowned in the River Aire after repeated severe beatings and harassment by two police officers.

|

The OCR Migration Course

|

The history of Black presence in Britain forms part of two courses (Migrants to Britain 1250 to present and Migration to Britain 1000 to 2010) that can be chosen as options in the new GCSE History courses run by examination board OCR. Starting in September 2016, these courses are supported by a range of resources including: official textbooks published by Hodder; online support materials from OCR; BBC Bitesize revision resources; BBC bitesize films presented by David Olusoga; and a resources hub provided by the Runnymede Trust with the support of the Universities of Manchester and Cambridge.

Schools doing the Migration to Britain 100 to 2010 course must also study the historic environment of a port community, looking at patterns of migration. The first of these, for students being examined in 2018, is Butetown in Cardiff. This will be followed by South Shields (Tyne and Wear), Spitalfields (London), Toxteth (Liverpool) and St Paul’s (Bristol). To obtain a copy of the OCR GCSE Migrants to Britain c.1250 to Present (see image right) go to: http://www.hoddereducation.co.uk/Product?Product=9781471860140 |