By Ed Hardiman

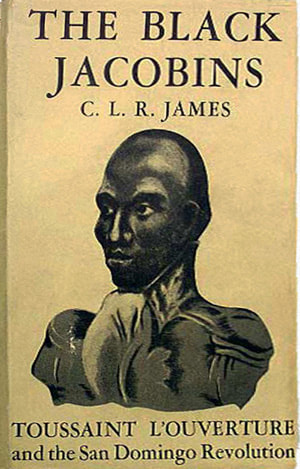

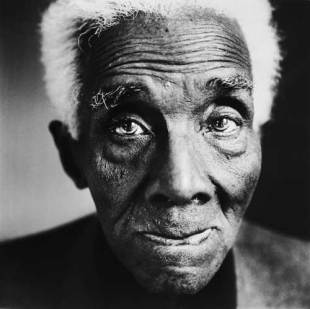

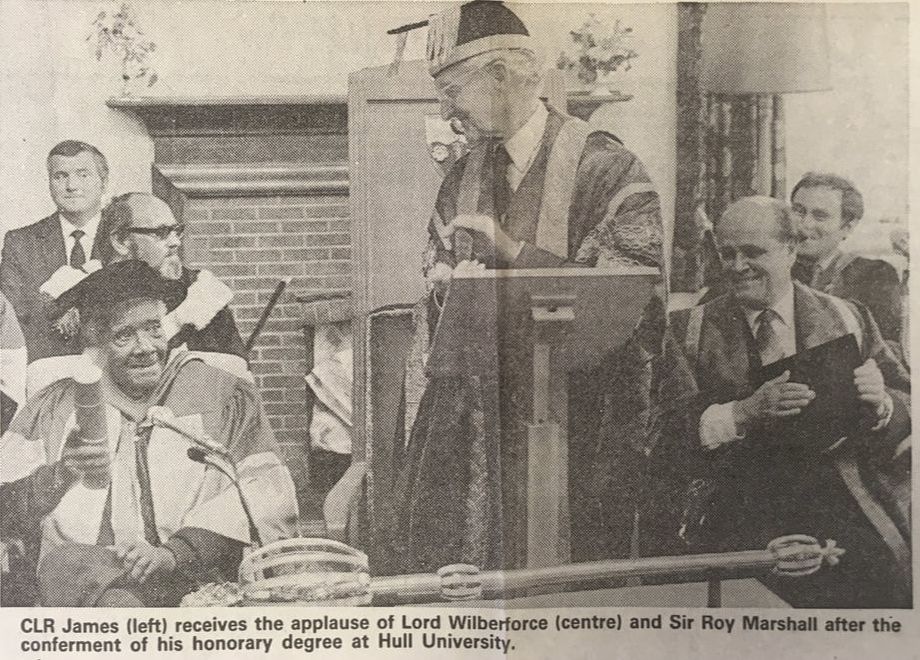

Cyril Lionel Robert James, or Nello as he was known to his friends, or even simply C.L.R. as he was often referred to in print, was many things in his life. Many people knew him as simply the author of The Black Jacobins (1938) an excellent history of the Haitian revolution.[1] Others are aware of his work as a socialist activist and advocate for Trotsky. However, his work as a cricket correspondent and co-authorship of Learie Constantine’s Cricket and I (1933) is also widely considered to be noteworthy and insightful concerning the sport of cricket. James was, chiefly, a man of many talents. These talents were in fact officially recognised and commended by the University of Hull in 1983. James received an honorary degree not only in the 150th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in the British Empire but also by a descendent of William Wilberforce who was the University Chancellor at the time.[2] His mark can still be found within Hull, with the original manuscript of his play Toussaint L’Overture residing in the Hull History Centre bearing James’s original annotations.[3]

James was born in 1901 in Trinidad. His grandparents had originally migrated from Barbados and his parents were both from a middle-class background. His mother played a hugely important part in James’s life, fostering his love of classic English literature such as Shakespeare and Dickens. With this early love of literature also came a natural academic ability, so much so that James was able to achieve a scholarship to Queen’s Royal College in 1910. Despite this early ability James lacked the desire for academic success, he refused to become a civil servant or enter the world of academia through Oxford or Cambridge. Instead, in true rebellious style, he entered the literary circles of the pioneering Trinidadian authors Albert Gomes and Alfred Mendes, writing short stories, essays and a novel called Minty Alley, written in 1928 but not published until 1936. Even within his early work, James focused on the working class of Trinidad, Minty Alley specifically looks at the idea of Caribbean identity and culture. This identity and culture, according to James, was found in the working class over any other part of society.[4] Trinidad was however too restrictive for James, yet it was not politics or literature that motivated his move to England, it was cricket.

|

His eventual move to England in 1932 was prompted by his acquaintance with the famous cricketer Learie Constantine who had moved to England in order to play professionally in the Lancashire league. James lived with Constantine in the working-class town of Nelson.[5] The experience of living in Nelson only seemed to enhance his support for the working-class and their hardships.[6] In 1933 James collaborated with Constantine, helping him write his autobiography Cricket and I. For a time, James’s main source of income was from his job as a cricket correspondent for the Manchester Guardian. During his time as a correspondent he moved to London in 1934 where he was able to mix with the Independent Labour party and the Troskyist faction within it. England therefore acted as both a political and sporting catalyst for James and his work. This first move to England in the 1930s proved to be a milestone in James’s literary career. He wrote and published several polemical historical works, most notably A History of Negro Revolt (1938) and The Black Jacobins (1938). As he had done in the past, James did not simply limit himself to history books, he also produced a play called Toussaint L’Ouverture which later became The Black Jacobins, which had a short run in London in 1936 with Paul Robeson as the eponymous Toussaint.[7] The Black Jacobins was not merely a chronicle of the events of the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) but a manifesto for the many anti-colonial revolts throughout the British Empire.[8] James seemed to refute the idea that history was simply for its own sake, instead his work illustrated a need to use the past in order to understand the present.

|

Although he would eventually reside in England his first visit was not for long. In 1938 James travelled to Paris and then America as a delegate of Trotsky’s Fourth International. The trip to America was only intended to be for around a year, however James was unable to return to England due to the outbreak of the Second World War on mainland Europe. America would unfortunately prove to be extremely difficult both politically and personally for James. As a hard-line socialist and Troskyist he was scrutinized by the American government which strongly opposed communism in all its manifestations. This scrutiny reached its zenith in 1952 during the second ‘Red Scare’[9] when he was arrested for ‘passport violations’.[10] To add to that James was a Black man in a white racist society. It is not hard to imagine the massive difficulties he faced living in a society where he was in almost every sense considered an ‘outsider’. On a personal level, James became infatuated with a much younger woman whom he eventually married and had a child with in 1949; however, this marriage was tumultuous and ended in their divorce in 1951 much to James’s dismay.[11] James’s time spent in America clearly marked a very difficult period in his life.

|

The difficulties that James faced in America however did not deter his desire to travel. He returned to England in 1953, living mostly in London, but also guest lecturing at several universities across America and Europe.[12] The Prime Minister of Trinidad, Eric Williams, who had been a pupil of James’s at school, even urged him to return to Trinidad. For a short period of time James took up this offer and stayed in Trinidad, however James’s political leanings towards radical socialism opposed Williams’s more conservative government and decided to leave the country of his birth. James was uncompromising in his beliefs. Upon returning to England in 1962 he again refused to completely settle, continuing to lecture abroad in countries such as Cuba, Uganda, Tanzania, and Canada.

He came to Hull in 1983 to receive an honorary degree from the University, whilst there he met and spoke with Sir Hilary Beckles – historian and current vice-chancellor of the University of the West Indies – urging him to focus his historical efforts on a history of the West Indies and their contribution to cricket.[13] Even at that late point in his life C. L. R. James never stopped being a fervent advocate for the things he loved.

|

Footnotes

[1] S. Howe, ‘James, Cyril Lionel Robert (1901–1989)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/59637, accessed 17 July 2017]

[2] Hull Daily Mail

[3] Hull History Centre U DJH/21/1

[4] This subject is furthered analysed and discussed within Nicole King’s chapter ‘Framing Community Minty Alley, La Rue Cases Negres, and Class Consciousness’, in her book, C. L. R. James and Creolization: Circles of Influence (University Press of Mississippi, 2001) Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2tvmzn?refreqid=excelsior%3A4fea389b43a229f9bd33e0948d2f8adb

[5] ‘Life in the District 25 Years Ago’ Nelson Leader, 24 May 1957, 4.

[6] Howe, ‘James, Cyril Lionel Robert (1901–1989)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/59637, accessed 17 July 2017]

[7] Paul Robeson Speaks: Writings Speeches Interviews 1918-1974, edited, introduced by P. S. Foner (London: Quartet Books Limited 1978), 31.

[8] Howe, ‘James, Cyril Lionel Robert (1901–1989)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/59637, accessed 17 July 2017]

[9] Sometimes referred to as ‘McCarthyism’, the second ‘Red Scare’ was a period occurring directly after the Second World War until the late 1950s of paranoia within American culture and politics concerning communist espionage and infiltration into the country.

[10] Howe, ‘James, Cyril Lionel Robert (1901–1989)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/59637, accessed 17 July 2017]

[11] ibid

[12] ibid

[13] H. Beckles, ‘James’s Beyond a Boundary: From Liberation and Nationalism to Globalization and Commodification in the West Indies’, in J Nauright et al’s Beyond C. L. R. James: Shifting Boundaries of Race and Ethnicity in Sports, (University of Arkansas Press, 2014) 7-16.

[1] S. Howe, ‘James, Cyril Lionel Robert (1901–1989)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/59637, accessed 17 July 2017]

[2] Hull Daily Mail

[3] Hull History Centre U DJH/21/1

[4] This subject is furthered analysed and discussed within Nicole King’s chapter ‘Framing Community Minty Alley, La Rue Cases Negres, and Class Consciousness’, in her book, C. L. R. James and Creolization: Circles of Influence (University Press of Mississippi, 2001) Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2tvmzn?refreqid=excelsior%3A4fea389b43a229f9bd33e0948d2f8adb

[5] ‘Life in the District 25 Years Ago’ Nelson Leader, 24 May 1957, 4.

[6] Howe, ‘James, Cyril Lionel Robert (1901–1989)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/59637, accessed 17 July 2017]

[7] Paul Robeson Speaks: Writings Speeches Interviews 1918-1974, edited, introduced by P. S. Foner (London: Quartet Books Limited 1978), 31.

[8] Howe, ‘James, Cyril Lionel Robert (1901–1989)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/59637, accessed 17 July 2017]

[9] Sometimes referred to as ‘McCarthyism’, the second ‘Red Scare’ was a period occurring directly after the Second World War until the late 1950s of paranoia within American culture and politics concerning communist espionage and infiltration into the country.

[10] Howe, ‘James, Cyril Lionel Robert (1901–1989)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/59637, accessed 17 July 2017]

[11] ibid

[12] ibid

[13] H. Beckles, ‘James’s Beyond a Boundary: From Liberation and Nationalism to Globalization and Commodification in the West Indies’, in J Nauright et al’s Beyond C. L. R. James: Shifting Boundaries of Race and Ethnicity in Sports, (University of Arkansas Press, 2014) 7-16.