Desmond Tutu is a South African Anglican clergyman, famous particularly for his social rights activism. He visited Hull on four occasions between 1989 and 2007. During his time in the region he delivered a civic service at the Holy Trinity Parish Church, received the Freedom of the City, delivered the fifth Wilberforce Lecture and has been presented with the Wilberforce Medal from the Queen. Tutu has also visited Hull University and the Wilberforce Institute for the Study of Slavery and Emancipation, where he remains the patron.

Desmond Tutu was born on 7 October 1931 in Klerksdorp, South Africa. His father was the headmaster of a local Methodist Primary School and his mother, Aletha Matlhare, was a domestic servant. Tutu had a difficult childhood for many reasons. Not only was he the victim of racism, he also faced life-threatening illnesses such as polio and tuberculosis (TB).[1] His bout with TB, however, had to some extent, a silver lining. It was during his treatment at the Rietfontein Hospital that he met Father Huddleston, who acted as the intellectual and spiritualist catalyst for his thirst for learning.[2] Huddleston brought him school work and American comic books to make sure he didn’t fall behind with his education and to keep his mind occupied during his lengthy stay in hospital.[3]

In the late 1940s, as apartheid was officially implemented, politics in South Africa became extremely volatile. It is within this context that Tutu began his career as a teacher. Originally Tutu wanted to become a doctor and gained a place at Witwatersrand Medical School but was unable to get a bursary, thus making it financially impossible for him to study there.[4] With that avenue no longer available, in 1951, Tutu decided to study for a teaching diploma at the Bantu Normal College, obtaining his teaching qualifications in 1954. He was employed at his old school, Midibane High, where he completed his BA from the University of South Africa.[5] Tutu was a voracious learner but also an excellent teacher. He bonded with his students and encouraged them to reach their potential academically in an era when the government was enforcing further harsh policies to quash Black African ambition and aspirations with the Bantu Education Act (1955). The Act declared that Black Africans should aspire to nothing higher than ‘certain forms of labour’ infuriating educators like Tutu.[6] As a result of these discriminatory practices, Tutu left education and began his religious career in 1955 as a sub-Deacon at Krugersdorp.

In 1962 Tutu earned a scholarship to study theology at King’s College, London. He left South Africa at a time when peaceful protests against the apartheid government were being abandoned as political activists began blowing up government buildings in Johannesburg and Port Elizabeth. South Africa was on the cusp of its darkest decade which would see Nelson Mandela arrested and hope for Black liberation almost extinguished.[7] Tutu was yet to become fully entangled in the vast web that was apartheid politics - he was not yet a leader of the resistance. However, his time in Britain would have a profound impact on him which fostered a desire to change discriminatory practices in his home country.[8] Of course, Britain was not free from racism, Enoch Powell’s infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech was made in 1968, but Tutu’s time in the capital illustrated that there was an alternative to apartheid, despite Powell's rhetoric.

After completing his scholarship, Tutu returned to South Africa. While he was in Britain, key Black African leaders had been imprisoned or exiled and their organisations banned; Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress being perhaps the most well-known.[9] Tutu’s first major involvement with anti-apartheid activism was in 1976 when protests were held in Soweto after a large group of Black school children who had marched into a football stadium, had been fired upon by the police. The attack and chaotic aftermath led to over 600 deaths and thousands of people injured.[10] Tutu used his position as the Secretary-General of the South African Council of Churches, and the Archbishop of Cape Town to protect political dissidents and their families, and helped educate their children.[11] Both of these prominent religious positions, also enabled Tutu to travel across Africa and visit many of the newly created countries such as Zaire (later to become the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe). These experiences further shaped his politics and rhetoric. Tutu was not simply an advocate for Black liberation but also racial harmony. He visited Uganda under Idi Amin and witnessed oppression that transcended race.[12] In 1984, Tutu received the Nobel Peace Prize for his important contribution in unifying the campaign to resolve the problems of apartheid in South Africa. However, it was acknowledged that his work was far from complete.

|

Visits to Hull - February 1989

Tutu strongly believed that the use of external diplomatic pressure was the key to breaking apartheid. He promoted economic sanctions from countries such as America and Britain advising they would force the South African government to abandon its internal policies of segregation and racism. It was in this context that Tutu made his first visit to Hull on 1 February 1989, to give a civic service at the Holy Trinity Parish Church.[13] The Archbishop of Cape Town used the occasion to launch a passionate attack on the British government for failing to impose economic sanctions on South Africa. He pleaded with the congregation to do all in their power to put pressure on the British government to intervene and persuade his own government to end apartheid. He highlighted the good work of local hero William Wilberforce and urged the people of Hull to follow in his footsteps by campaigning for global human rights.[14] During his visit, Tutu laid a wreath at the foot of the Wilberforce monument and described the abolitionist as ‘Hull's greatest son.’[15] He also received the Freedom of the City award in person which he had accepted in absentia in 1987.[16] In 1991, the apartheid regime came to an end when the laws implementing racial segregation were abolished. Although, Tutu was instrumental in the campaign, he was quoted saying that he was neither a politician nor a leader of Black Africans in South Africa, since ‘our real leaders are in prison and in exile.’[17] With Nelson Mandela released from prison alongside many other Black African leaders, Tutu left his political leadership role, but this did not spell the end of his activism.

|

Tutu preaching at Holy Trinity Church, Hull, 1989

|

|

June 1999

In June 1999, Tutu arrived in Hull for the second time. The purpose of his visit was to give the fifth annual Wilberforce lecture as part of a series of special Nobel Prize winning speakers to celebrate Hulls 700th anniversary. To welcome the Archbishop and to announce its peace commission, Time Based Arts released 700 balloons.[18] On 4 June, he gave the Wilberforce lecture to a crowd of approximately 2,500 people in Queens Gardens. He received a welcome to the stage by the leader of Kingston upon Hull City Council, Patrick Doyle. Tutu began his speech entitled ‘The New Economic Slavery Brought About by International Debt’ by interacting with the crowd and praising the people of Hull for their historical support of freedom and emancipation including their help in South Africa’s fight against apartheid. Tutu declared, “Our victory is your victory, and we know how passionate and strong the support was that came from the people of Hull. In the darkest days of our struggle to show your commitment, you gave me the freedom of your city to proclaim your unswerving support.” He went on to state, “Now that Apartheid is ended, the next moral issue for the world is this international debt.” And I ask you, people of Hull, my city, and I’ll maybe say so tomorrow, when I speak to what will then be my university, the University of Hull. I will say, dear fellow members of this great university, please be enthusiastic supporters of Jubilee 2000 because there they are saying let’s scrap the debt as we enter this new millennium. Give people in poor countries the opportunity of making a new beginning.” |

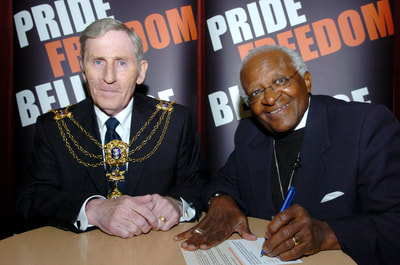

The Queen presents Archibishop Tutu with the Wilberforce Medal at the Guildhall, Hull. June 1999

|

After his speech, Deputy Prime Minister and vice-president of the Anti-Slavery Society, John Prescott, then offered a vote of thanks to Tutu.[19] He stated that Hull was proud to have Archbishop Tutu as a Freeman of the City and he congratulated South Africa and the ANC on their second landslide victory in the elections. Following the Wilberforce lecture, Tutu attended a special ceremony at Hull’s Guildhall and was presented with the Wilberforce medal by Her Majesty the Queen.[20]

The following day, Tutu obtained an Honorary degree from the University of Hull where he showed his thanks to members of University staff and students with a short speech. During this visit, Tutu also took the time to present an award to a community group, which helped Bransholme residents gain over 90 qualifications.[21] Although, he left the region shortly after, his fondness for the city was reconfirmed later that year. As part of the city’s 700th anniversary celebrations, in December 1999, 300 pupils from schools in Hull participated in a performance which detailed the 2,000 years since Christ’s birth. To mark the event, officials at Hull City Council wrote to Tutu to tell him about the concert. The Archbishop responded by sending a fax which said, 'I think everywhere the world is holding its breath hoping for a new dawn, a new age, a new Millennium.[22]

|

June 2005

Tutu’s ties with Hull were cemented in 2005 when he accepted the role of patron at the Wilberforce Institute for the Study of Slavery and Emancipation (WISE) before it officially opened in 2006. He said: "It is exemplary the university should build on the history of the city and one of its most outstanding citizens. He also remarked that "Tragically, slavery and the violation of human rights are still with us in the 21st century. The institute will be a beacon that will continue to throw a light on issues that are too often overlooked." [23] In early June 2005, Tutu also gave a keynote lecture at the Yorkshire International Business Convention at the KC stadium. The event twinned with the main conference at Harrogate, and speakers such as Archbishop Tutu were taken by helicopter between the two venues.[24] During this event Tutu stated that he believed Hull's heritage could be the inspiration for greater racial harmony across the UK and that ‘the birthplace of anti-slavery crusader William Wilberforce has the authority to help different ethnic groups unite.’[25] On 13 June Tutu visited WISE and discussed themes of ‘race relations, the plight of disenfranchised communities and modern forms of slavery.’[26] Tutu also features on the WISE Humanitarian Wall. After he had toured the building, he visited Wilberforce House Museum and urged people to learn from history as he stood under the statue of the abolitionist in the front garden. He also claimed that Wilberforce made him proud to be a human. [27] |

May 2007

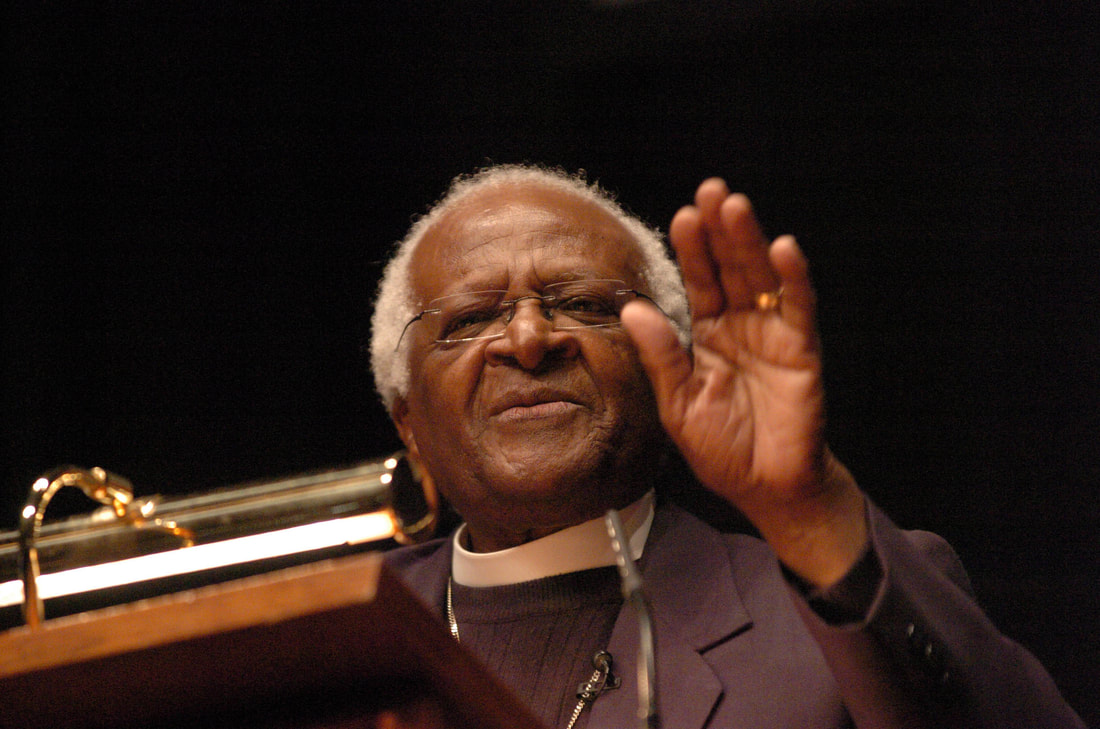

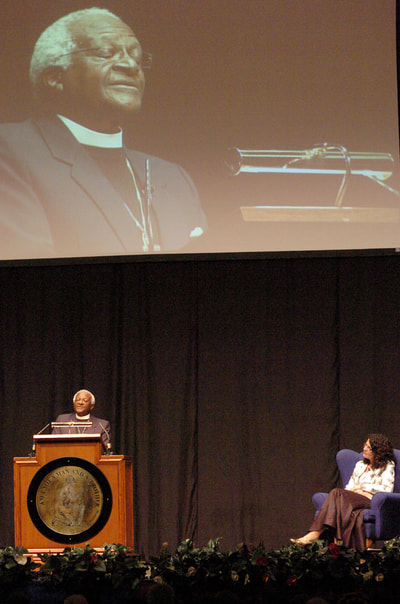

In May 2007, Tutu returned to Hull to participate in a three-day event hosted by WISE where he delivered a lecture entitled ‘Emancipation, Reconciliation and Reparations,’ at Hull City Hall.[28] The day before this event, he also gave a talk at the University of Hull to staff and students.

Desmond Tutu is a remarkable man. He continues to be a vocal critic of abuses on human rights, and has been involved in conflicts in Northern Ireland, Tibet, Rwanda, and Darfur. His influence on Hull has also been profound. To date he is the sole patron of the Wilberforce Institute for the study of Slavery and Emancipation. He has always been an advocate for not just black liberation, although his contribution to that cause has been unwavering, but almost all forms of liberation from oppression. [29]

In May 2007, Tutu returned to Hull to participate in a three-day event hosted by WISE where he delivered a lecture entitled ‘Emancipation, Reconciliation and Reparations,’ at Hull City Hall.[28] The day before this event, he also gave a talk at the University of Hull to staff and students.

Desmond Tutu is a remarkable man. He continues to be a vocal critic of abuses on human rights, and has been involved in conflicts in Northern Ireland, Tibet, Rwanda, and Darfur. His influence on Hull has also been profound. To date he is the sole patron of the Wilberforce Institute for the study of Slavery and Emancipation. He has always been an advocate for not just black liberation, although his contribution to that cause has been unwavering, but almost all forms of liberation from oppression. [29]

Archibishop Tutu visits Hull in 2007: photos courtesy of WISE

click images to enlarge

click images to enlarge

Thanks go to Ed Hardiman for providing the historical context for this piece.

Footnotes

[1] J Allen, Rabble-Rouser for peace: The Authorised biography of Desmond Tutu, (London: Random House Group: 2006), p. 19 and S Du Boulay, Tutu: Voice of the Voiceless, (London: Holder & Stoughton), p. 30.

[2] S Du Boulay, Tutu: Voice of the Voiceless, p. 30.

[3] Ibid, p. 31

[4] Ibid, p. 36

[5] Ibid, p. 36-37.

[6] Ibid, p. 44

[7] A Sparks & M Tutu, Tutu Authorised, (New York: Harper Collins, 2011), p. 52.

[8] Ibid, p. 59

[9] For more information on this topic see, M. Morris, Apartheid: An Illustrated History, (Sunbird Publishers Ltd, 2011)

[10] A Sparks & M Tutu, Tutu Authorised, p. 2

[11] Ibid, p. 74

[12] Ibid, p. 74

[13] Hull Daily Mail, 1 June 1999 p. 10

[14] Ibid, p. 10

[15] Ibid, p. 10

[16] Hull Daily Mail, 5 June 1999, p. 22.

[17] Ibid, p. 2

[18] Hull Daily Mail, 3 June 1999, p. 14

[19] Hull Daily Mail, 8 June 1999, p. 2

[20] Hull Daily Mail, 5 June 1999, p. 1

[21] Hull Daily Mail, 3 June 1999, p. 7.

[22] Hull Daily Mail, 8 December 1999, p. 7

[23] Hull Daily Mail, 5 February 2005, p.1

[24] Hull Daily Mail, 18 February 2005, p. 12

[25] Hull Daily Mail, 11 June 2005, p. 4

[26] Hull Daily Mail, 13 June 2005, p. 3

[27] Hull Daily Mail, 15 June 2005, p. 3

[28] Hull Daily Mail, 16 May 2007, p. 16

[29] C Johnston, ‘Slavery research centre opens at Hull’, The Guardian, July 2006

[1] J Allen, Rabble-Rouser for peace: The Authorised biography of Desmond Tutu, (London: Random House Group: 2006), p. 19 and S Du Boulay, Tutu: Voice of the Voiceless, (London: Holder & Stoughton), p. 30.

[2] S Du Boulay, Tutu: Voice of the Voiceless, p. 30.

[3] Ibid, p. 31

[4] Ibid, p. 36

[5] Ibid, p. 36-37.

[6] Ibid, p. 44

[7] A Sparks & M Tutu, Tutu Authorised, (New York: Harper Collins, 2011), p. 52.

[8] Ibid, p. 59

[9] For more information on this topic see, M. Morris, Apartheid: An Illustrated History, (Sunbird Publishers Ltd, 2011)

[10] A Sparks & M Tutu, Tutu Authorised, p. 2

[11] Ibid, p. 74

[12] Ibid, p. 74

[13] Hull Daily Mail, 1 June 1999 p. 10

[14] Ibid, p. 10

[15] Ibid, p. 10

[16] Hull Daily Mail, 5 June 1999, p. 22.

[17] Ibid, p. 2

[18] Hull Daily Mail, 3 June 1999, p. 14

[19] Hull Daily Mail, 8 June 1999, p. 2

[20] Hull Daily Mail, 5 June 1999, p. 1

[21] Hull Daily Mail, 3 June 1999, p. 7.

[22] Hull Daily Mail, 8 December 1999, p. 7

[23] Hull Daily Mail, 5 February 2005, p.1

[24] Hull Daily Mail, 18 February 2005, p. 12

[25] Hull Daily Mail, 11 June 2005, p. 4

[26] Hull Daily Mail, 13 June 2005, p. 3

[27] Hull Daily Mail, 15 June 2005, p. 3

[28] Hull Daily Mail, 16 May 2007, p. 16

[29] C Johnston, ‘Slavery research centre opens at Hull’, The Guardian, July 2006