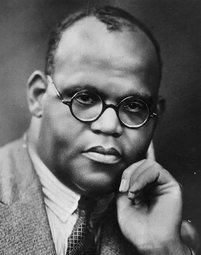

Doctor Harold Arundel Moody is one of the most famous people of African descent to have visited Hull and East Yorkshire in the first half of the twentieth century. His campaign for racial equality as the founder and chairman of the League of Coloured Peoples brought him to Hull in July 1933 for the William Wilberforce centenary celebrations. He later visited various churches in the region as the head of the London Missionary Society.

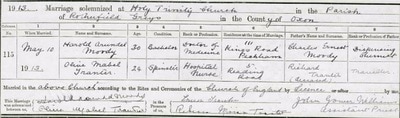

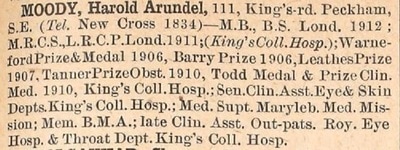

Moody was born on 8 October 1882 in Kingston, Jamaica. As the eldest child of a modestly wealthy family, he received a good education in the Caribbean and excelled academically. At the age of 22, Moody relocated to Britain to train as a doctor at King's College London. His interest in medical studies was probably inspired by his father Charles, who worked as a chemist in Jamaica. On his arrival in London, Moody quickly discovered that in Edwardian Britain racial discrimination was omnipresent. Like most West Indian men and women, he found it exceptionally difficult to find a place to stay because he was Black. It is probable that this was the first time Moody had witnessed the effects of racism and the colour bar. However, it would not be the last. In 1910 after he had won several prestigious prizes, he was refused a job in a hospital because the matron did not think it was appropriate to hire a Black doctor. Three years later, after several rejections for jobs due to prejudice, the Jamaican doctor set up his own practice in Peckham. In the same year, he married white British nurse Olive Mabel Tranter in Oxfordshire on 10 May 1913 and settled into family life. The couple had six children in their long happy marriage.

|

Despite the adversity he faced in Britain, Moody was keen to keep a strong connection with the Caribbean and crossed the Atlantic several times during his life to visit his family. The Jamaican social, moral and religious values which were instilled in Moody during his childhood later influenced his work for the church and fight for racial equality. In Jamaica, Moody had been brought up as a strict Congregationalist and when he moved to Britain his dedication to the church enabled him to secure two high profile appointments. In 1921, Moody became the chair of the Colonial Missionary Society’s board of directors and a decade later was appointed president of the London Christian Endeavour Federation. The connections he made through both organisations were pivotal in his endeavours to redress the race issue in Britain.[1] In both roles Moody became aware of other men and women who were deeply disturbed by the racism present in British society. Thus, on 13 March 1931, Moody formed the League of Coloured Peoples at the YMCA situated on Tottenham Court Road in London. Founding members included Belfield Clark, George Roberts, Samson Morris, Robert Adams, Desmond Buckle, C. L. R. James, Jomo Kenyatta and Una Marson. Their aims were to protect the social, educational, economic and political interests of their members, and secondly to interest members in the welfare of coloured peoples in all parts of the world. Thirdly it was the group's mission to improve relations between the races and finally to cooperate and affiliate with organisations sympathetic to coloured people. A further aim was added in 1937 which was to render such financial assistance to coloured people in distress. The League of Coloured Peoples grappled with human rights, racial equality and community integration but ultimately, they wanted to stop the effects of the colour bar in Britain.

|

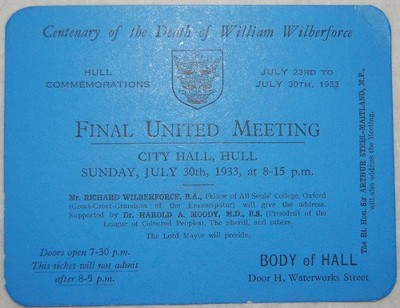

As chairman of the League of Coloured Peoples, Moody was invited to the William Wilberforce Centenary celebrations which took place in Hull in July 1933. On 24 July, together with other notable people, Moody attended a Civic Reception at the Guildhall. Six days later Moody was one of the main attractions at the final united meeting which formally ended the celebrations. After Richard Wilberforce had finished his speech, Moody joked to those gathered ‘that he could not by the wildest stretch of the imagination claim to be a descendent of Wilberforce, and that he could only assume that he had been invited to the function to give colour to the proceedings,’ to which the crowd responded with laughter.[2] In the emotionally charged speech, Moody stated that he found it an honour to have been invited to talk at the event. He then went on to point out that if Black men and women had not proven themselves worthy of Wilberforce’s achievements there would have been no celebration of his life. The Jamaican advised “May I remind you also that the great work of Wilberforce was made necessary, not because of the sins of my own people, but the sins, the selfishness, and the short-sightedness of your own people.”[3] He then moved on to discuss Wilberforce’s role in the abolition of the slave trade and spoke about later slavery in the British colonies. Moody concluded, “The greatest tribute I can pay Wilberforce is to say that the coloured races today are determined to do everything in their power to emancipate themselves from all those things which are preventing them from giving their fullest expression to the life of the world in which they live, and the best tribute you can pay is to do everything in your power to assist against the slavery which does exist.” An expanded version of his speech can be found in the October edition of the Keys which can be found by through the National Archives Moving Here archives.

Over the subsequent decade, Moody and the League of Coloured Peoples continued to campaign for economic and social equality. They worked hard to remove the stigma attached to skin colour and provided much needed relief to Black migrants who relocated from Africa and the West Indies. They also mounted attacks on the colour bar which saw a relaxation of exclusionary practices in the forces during World War Two.

Click to enlarge images

In the war years, Moody travelled to Hull once again, on this occasion however, it was his involvement with the church that brought him to the region.[4] On 27 and 28 November 1943, he visited the Memorial Church in Hull as well as the Hessle and Newland Congregational Churches.[5] On 29 November, Moody was given civic recognition at a lunch held by the Lord Mayor.[6] The gathering was to celebrate Moody’s position as the chairman of the London Missionary Society. The guests included Lord Mayor Alderman F. R. Fryer, the Lady Mayoress, the Sheriff and his wife, among others. A warm welcome was extended to Dr Moody by the Lord Mayor, who spoke of the extensive work undertaken by the London Missionary Society. The Sheriff then spoke about Christian religion and the hope for peace.[7] That evening Moody visited Beverley Lairgate Congregational Church. His final day in the region was spent in Cottingham at a meeting at the Zion Church.’[8] Additional research could possibly reveal that Black American GI’s may well have seen and spoken to Moody during their time in Cottingham. Moody and the League of Coloured Peoples were advocates for racial equality in the armed forces. They were aware of wartime racism at home and overseas and became champions for the better treatment of Black service personnel. The group had condemned practices of segregation and the implementation of harsh punishment in the American Army. Thus, it is probable that if Moody was aware of their presence, he may have chosen to meet with the America GIs to speak about their experiences in Britain.

After his last visit to Hull, Moody continued his endeavours to improve the lives of Black men and women in Britain. In January 1947, he began a fundraiser in Kingston, Jamaica which aimed to raise £50,000 to provide a cultural centre for West Indians and Africans in London.[9] After a strenuous five-month visit to the West Indies and America, he returned to England a very ill man. Sadly Moody died ten days later, on 24th April 1947. [10]

Footnotes

[1] Roderick J. Macdonald, Dr Harold Arundel Moody and the League of Coloured Peoples, 1931-1947: A Retrospective View, Race and Class, 14:3 (1973), pp. 291-310.

[2] Hull Daily Mail, 25 July 1933, p. 7

[3] Ibid

[4] Hull Daily Mail, 26 November 1943, p. 3

[5] Hull Daily Mail, 26 November 1943, p. 2

[6] Hull Daily Mail, 30 November 1943, p. 3

[7] Ibid, p. 3

[8] Ibid

[9] Hull Daily Mail, 24 January 1947, p. 6.

[10] 100 Great Black Britons, http://www.100greatblackbritons.com/bios/harold_moody.html accessed 20/05/17

[1] Roderick J. Macdonald, Dr Harold Arundel Moody and the League of Coloured Peoples, 1931-1947: A Retrospective View, Race and Class, 14:3 (1973), pp. 291-310.

[2] Hull Daily Mail, 25 July 1933, p. 7

[3] Ibid

[4] Hull Daily Mail, 26 November 1943, p. 3

[5] Hull Daily Mail, 26 November 1943, p. 2

[6] Hull Daily Mail, 30 November 1943, p. 3

[7] Ibid, p. 3

[8] Ibid

[9] Hull Daily Mail, 24 January 1947, p. 6.

[10] 100 Great Black Britons, http://www.100greatblackbritons.com/bios/harold_moody.html accessed 20/05/17