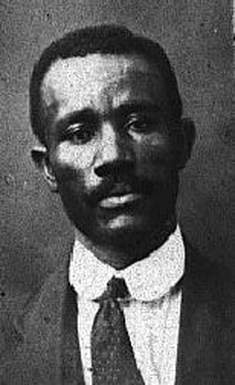

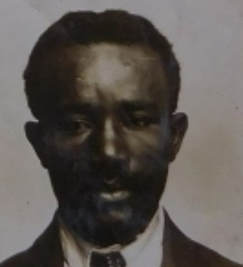

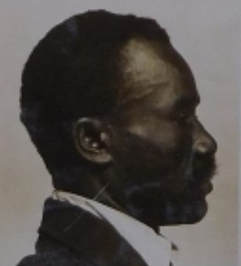

From its opening in 1870, Hull prison has housed some notorious killers. Most of these criminals have received sentences of life imprisonment for their crimes. However, before the abolition of capital punishment for murder in 1965, one woman and nine men were hanged behind the prison walls. One of these men was West Indian George Emanuel Michael who was executed on 27 April 1932.

|

George Emanuel Michael was born on the small West Indian island of Saint Croix on 12 April 1882. Although, very little is known about his family or early life, he must have grown up on the Caribbean island as he was still living there at the age of 19.[1] A census conducted in October 1901, recorded that he was an unmarried, Roman Catholic field labourer who lived at 38 Queen Quarter, Montpellier, St Croix.[2]

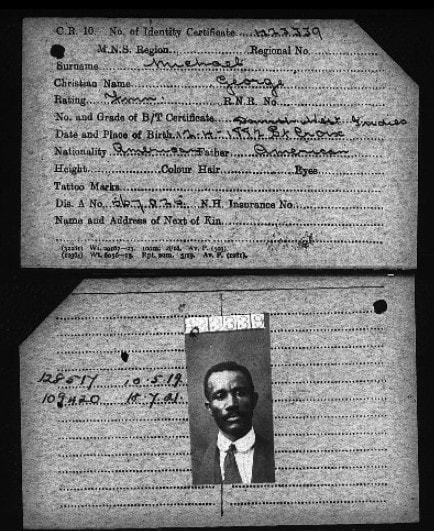

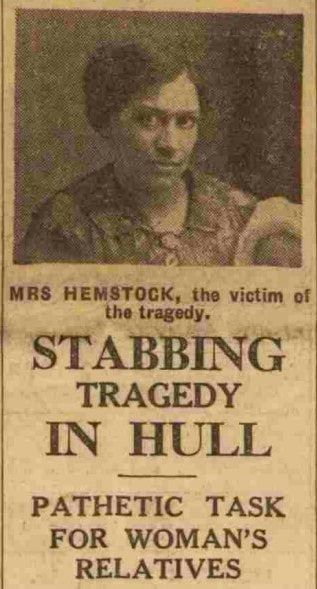

Although it is difficult to determine when Michael travelled to Britain, like many men from the West Indies, he was part of the Merchant Marine during the First World War. It is probable that he crossed the Atlantic as an unskilled sailor in the engine room of a vessel in the early twentieth century and continued his career as a ship’s fireman throughout the conflict. Michael sailed from various major British ports after the war. His Merchant Marine Ribbon was issued in Cardiff on 8 September 1919. However, his medal was sent to the shipping office in Liverpool on 15 April 1921.[3] It is probable that Michael settled in Hull in the 1920s. In the winter of 1929, he married local born Theresa Mary Clara Hempstock, who was reportedly a woman of mixed heritage.[4] Although, there is no evidence as to how or where the couple met, given Michael was a sailor and Hempstock had relatives in the shipping community, it is likely that they came into |

contact in Hull’s bustling maritime quarter. The couple were both in their forties when they were married and appear to have had a volatile relationship. Within a year of their nuptials, Michael had been sent to prison for 11 months for wounding Hempstock and her daughter from a previous relationship, Agnes Colboun.[5] Although, their marriage may have been strained, when Michael was released from prison it is likely that he returned to the family home.

|

On the morning of 12 December 1931, Hempstock visited a police station to confess, that in marrying Michael two years earlier she had committed the crime of bigamy. On 13 September 1899, at the age of 18, Theresa Walton had married 19-year-old Solomon Hempstock in St James’ church, Hull. The couple were still together in 1901 and lived at 10 Queen’s Place. However, by 1911 Solomon was living with Ada M. Farrell, who was according to the census of that year, his housekeeper, although he married her very quickly after his first wife’s death. Despite their lengthy separation, the couple did not legally end their marriage by getting divorced and thus Hempstock’s wedding to Michael was unlawful. What perhaps makes Hempstock’s crime more spectacular is that Solomon appears to have lived in Hull until his death in 1952 and therefore must have known that she had committed bigamy but kept her secret. Shortly after her declaration, Hempstock appeared in front of a magistrate who adjourned her case until 6 January 1932 and granted her bail.[6]

|

On the afternoon of 12 December, Michael was notified of his wife’s admission. He responded with, “I’ll kill her. She’s done this to get rid of me.”[7] In the same week Michael had moved out of the family home to 9 Providence Terrace, where he rented a room. On 21 December, in a conversation with the landlady, he asked questions about whether she believed it was wicked to murder another person.[8]

The woman replied that she did and detailed the punishment for people who committed such an atrocious crime. In response Michael commented that in Denmark they did not have the death penalty, at which point the landlady begged him not to think about murdering anyone and suggested that he would get over his heartbreak once he had some time away at sea. He then confessed that he would never get over Hempstock’s betrayal.[9] He also told the landlady that his wife had been fraternising with other men, had committed adultery, taken all of his money and married him even though her first husband was still alive.[10]

|

Ten days later, on 31 December, Michael withdrew his money from the Post Office and purchased a sheath knife from the Iron Mongers. Around midday he visited 7 Upper Union Street, where Hempstock was residing, and tried to smash through the door between the yard and the scullery to gain entry.[11] However, he was unsuccessful at gaining entry, and at 3 pm he returned to the house and demanded that Hempstock come outside to speak with him. He was told by a lady in the house that he needed to get the police before he could see his wife, to which he responded, “Tell her to come out, I won’t do anything to her. By Jesus Christ I'll go to the gallows for her before I leave this bloody street.”[12] After hearing the commotion, a neighbour called the police and within a short period of time, P.C. Peam arrived to solve the domestic dispute.[13] Michael told the officer that he wanted his naturalisation papers, which he stated that his wife had in a drawer upstairs.[14] Hempstock then came to the door and declared that she did not have anything belonging to her husband. After the pair had argued a little more, Hempstock invited Peam into the house to show the policeman what her husband had done to the back door. Michael followed and admitted he had caused the damages but only because he wanted his papers. Hempstock then retrieved the drawer from upstairs and Michael angrily rifled through the items within it.[15] When he did not find his papers, he accused his

|

wife of hiding them which she denied. Losing his temper, Michael flew at her, striking Hempstock with his right hand. Although the policeman tried to intervene, he was no match for the West Indian who had drawn his knife and continued to beat and stab his wife.

Several men, including Mr T. Thornton, publican of the Drum and Cymbal, came rushing into the house when they heard Hempstock’s harrowing screams.[16] One of the men struck Michael several times with a stave causing him to fall on the knife and wound himself. The Black sailor was taken to Hull Royal Infirmary with several injuries including a deep wound to his chest. [17] Theresa Hempstock was pronounced dead at 4pm. Her cause of death was determined as a haemorrhage from a large wound to her left lung.[18] She was also taken to the hospital where her daughter, sister and aunt reportedly identified her body.[19] Despite Michael’s extensive wounds he made a full recovery and attended a trial for murder where he was given the death sentence. He was then placed in a condemned cell in Hull prison to await his fate.

|

On the night of 26 April 1932, it is likely that the executioner, Thomas Pierrepoint, who hanged approximately 294 criminals in his career which spanned over 70 years, and his assistant travelled to Hull prison.[20] During that night or the following morning Michael would have been weighed and measured so that Pierrepoint could set up the execution equipment in accordance with the long drop method. This practice ensured that the neck of a prisoner would be broken resulting in a quick death rather than being painfully strangled by the noose.

|

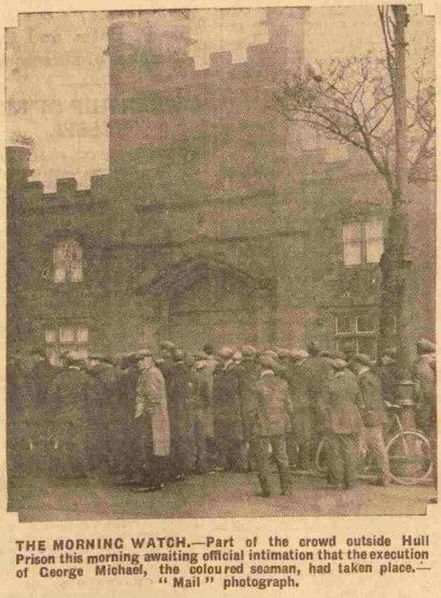

The following morning on 27 April, Michael spent the last hour of his life with the Roman Catholic Chaplain, Rev. Richard Fox, before being taken from the condemned cell through an adjoining door to the gallows. As it was expected that the execution would take place at 8 am, a large crowd had gathered outside the prison.[21] However, a notice had been put on the doors advising that the execution would take place an hour later. This gave time for the crowd to increase in size to between 200 and 300 people.[22] A small number of policemen patrolled the entrance to ensure those gathered did not gain entry to the prison. However, as was common practice, people had merely gathered to acknowledge that justice had been served. The Hull Daily Mail reported that there was ‘no tolling of a bell, and no hoisting of a flag. Not a hat or a cap was raised as the hands pointed to 9 o’clock; in fact, there was nothing but subdued chatter.’[23] At 9.10 am the small door in the prison gates swung open to reveal a warden carrying a noticeboard with two pieces of paper pinned to it. One contained the signatures of Frederick Hawksworth Fawkes, the Sheriff of Yorkshire, Chaplain Richard Fox and Governor of the prison, Captain E. D. Roberts confirming that the Black sailor had been executed: and the other, a letter from Ronald John Barlee, the prison surgeon confirming that he had examined Michael and he was dead.[24] Shortly, after the notices were read the crowd dispersed.

Footnotes

[1] Michael lists his father as American. However, St. Croix along with the remaining islands of the Dutch West Indies was sold to the USA in 1916. Therefore, it is possible that his father was from St. Croix which now forms part of the U.S. Virgin Islands.

[2] Virgin Islands Social History Associates (VISHA), comp. U.S. Virgin Islands Census, 1835-1911 (Danish Period) [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2009.

[3] The National Archives, Medals Awarded to World War One seaman, 1914-1925: BT 351-1-96895

[4] Ancestry.com. England & Wales, Civil Registration Marriage Index, 1916-2005 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc, 2010. It has been difficult to substantiate the claim that Hempstock was of African descent. For reference to her race see Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 1 January 1932, p. 15

[5] Leeds Mercury, 5 January 1932, p. 3.

[6] Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 1 January 1932, p. 15

[7] British Executions: George Emanuel Michael, http://www.britishexecutions.co.uk/execution-content.php?key=530 accessed 8/11/17

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid

[12] Ibid

[13] Hull Daily Mail, 1 January 1932, p. 1

[14] Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 1 January 1932, p. 15

[15] Ibid, p. 15

[16] Hull Daily Mail, 1 January 1932, p. 1

[17] Hull Daily Mail, 31 December 1931, p. 10 and Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 1 January 1932, p. 15

[18] British Executions: George Emanuel Michael

[19] Hull Daily Mail, 1 January 1932, p. 1

[20] It was common practice for the hangman to arrive at Hull prison the evening before an execution.

[21] Hull Daily Mail, 27 April 1932, p. 5

[22] Ibid, p. 5

[23] Ibid, p. 5

[24] Ibid, p. 5

[1] Michael lists his father as American. However, St. Croix along with the remaining islands of the Dutch West Indies was sold to the USA in 1916. Therefore, it is possible that his father was from St. Croix which now forms part of the U.S. Virgin Islands.

[2] Virgin Islands Social History Associates (VISHA), comp. U.S. Virgin Islands Census, 1835-1911 (Danish Period) [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2009.

[3] The National Archives, Medals Awarded to World War One seaman, 1914-1925: BT 351-1-96895

[4] Ancestry.com. England & Wales, Civil Registration Marriage Index, 1916-2005 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc, 2010. It has been difficult to substantiate the claim that Hempstock was of African descent. For reference to her race see Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 1 January 1932, p. 15

[5] Leeds Mercury, 5 January 1932, p. 3.

[6] Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 1 January 1932, p. 15

[7] British Executions: George Emanuel Michael, http://www.britishexecutions.co.uk/execution-content.php?key=530 accessed 8/11/17

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid

[12] Ibid

[13] Hull Daily Mail, 1 January 1932, p. 1

[14] Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 1 January 1932, p. 15

[15] Ibid, p. 15

[16] Hull Daily Mail, 1 January 1932, p. 1

[17] Hull Daily Mail, 31 December 1931, p. 10 and Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 1 January 1932, p. 15

[18] British Executions: George Emanuel Michael

[19] Hull Daily Mail, 1 January 1932, p. 1

[20] It was common practice for the hangman to arrive at Hull prison the evening before an execution.

[21] Hull Daily Mail, 27 April 1932, p. 5

[22] Ibid, p. 5

[23] Ibid, p. 5

[24] Ibid, p. 5