Written by Eleanor Rylatt and edited by Audrey Dewjee

"Music is going to play a great part in the working of the salvation of the negro race."

Will Marion Cook [1]

In Dahomey was the first full-length musical written and played by an entirely Black cast to be performed on Broadway. The play was based on a libretto by Jesse A. Shipp, with music by Will Marion Cook and lyrics by Paul Laurence Dunbar and Alex Rogers. Cook’s music would become to be considered by many as the ‘turning point for African American representation’. [2]

|

The plot of the play is complex and seems to be one that continued to evolve over time - something that makes it difficult to discern which version of the story was shown at certain theatres. However, at the Theatre Royal in Hull, the play opened with an overview of life in Dahomey before the audience was transported across the Atlantic to America. As the Hull Daily Mail pointed out, "afterwards it is all talk about going to Dahomey, though the audience knows, after the explanation of the prologue, that the company of blacks which gather in Boston and set out via Florida for Dahomey will never get there." Thus, the play was a satire on the American Colonization Society’s “Back to Africa” propaganda.

In trying to get to Africa, the characters encounter problems which make for comical errors and escapades to the delight of the audience. Two of the lead comic characters in the story are Bostonian detectives, 'Shylock Homestead' and 'Rareback Pinkerton', who are employed by “an old southern negro” named ‘Lightfoot’ to find a silver casket. [3] Their escapades, continually trying to outsmart one another, provided much amusement for theatregoers. Although somewhat thin, the plot was the perfect vehicle to highlight the comedy, singing and dancing talents of the cast.

|

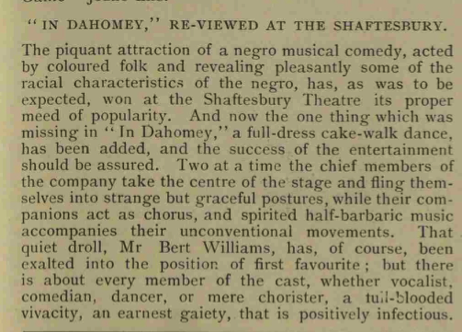

In Dahomey was certainly something new for British audiences. Prior to this, what largely passed for Black entertainment was minstrelsy, in which white performers donned blackface and pretended to be plantation workers from America, presenting songs and sketches which lampooned Black people as lazy, superstitious, dim-witted and happy-go-lucky. In Dahomey, with words and music created by talented African American writers and composers (albeit moderated by what they knew were the tastes of white audiences) was a completely different experience.

Original on Broadway

As the first African American show on Broadway, In Dahomey received excessive media attention. One New York newspaper stated that a "thundercloud had been hanging over the production" and people were terrified a "race war" would erupt on opening night. [4] As to be expected in late 20th Century in New York, seats in the theatre were racially segregated, yet despite these concerns no disruption occurred on opening night.

As the first African American show on Broadway, In Dahomey received excessive media attention. One New York newspaper stated that a "thundercloud had been hanging over the production" and people were terrified a "race war" would erupt on opening night. [4] As to be expected in late 20th Century in New York, seats in the theatre were racially segregated, yet despite these concerns no disruption occurred on opening night.

Will Marion Cook struggled to be accepted as a "serious" classical composer and performer, and he attributed this to "racial prejudices". Cook said that "the terrible difficulty that composers of my race have to deal with, is the refusal of American people to accept serious things from us." [5] Yet, read anything about In Dahomey and you will see that, both at the time and today, people around the world received the musical with open arms.

His perceptions are also reinforced by Jacob Noordermeer’s comment:

His perceptions are also reinforced by Jacob Noordermeer’s comment:

"…it is...striking that Will Marion Cook, a key contributor to this success, was led to writing for popular song because he was kept away from his true aspiration and talents in classical music. [...]while this musical was a step forward for black Broadway theatre, it is also linked to a demonstration of racial prejudice and social discrimination in the field of classical music." [6]

A critic in 1903 stated that it was "fresh" to experience music written and composed by "clever and able representatives of the negro race." [7] This occurred around the same period when Booker T. Washington’s Up From Slavery and W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk were published and so perhaps gives context to a period when African Americans were still experiencing intimidation and oppression.

The British newspaper, Weekly Despatch, referred to the musical as "the talk of the town." [8] However, not all shared this progressive attitude and some recoiled at the introduction of Black culture into the mainstream. One reporter stated that "chiefest and most deadly, the cakewalk tells us why the negro and white can never lie down together. It is a grotesque, savage, and lustful heathen dance" thus showing that post-Victorian society was shadowed with racial prejudice that clouded the success of In Dahomey. [9]

Coming to Britain

|

These concerns followed the cast to London at the Shaftesbury Theatre. Research by J. P. Green has described how members of London’s Black community, happy with the success of the show, had shown support and congregated in the vicinity of the theatre. Publicans complained of bad behaviour from certain elements and some refused to serve Black people as a result. Consequently, on 9th September 1903, the Westminster Gazette was one of the many newspapers forced to ask if there was "A Colour Line in London." Attempts, including legal action, were made to reverse the ban, and the matter was made public by a "black gentleman of culture and refinement…at present in this country studying our sociological conditions, a subject on which he is an authority." The sociologist may have been W. E. B. Du Bois. In the event, the episode demonstrated Black community interest and solidarity, as well as the determination of Black people to exercise their civil rights. [10]

Over one hundred cast members came to Britain, with Bert Williams and George Walker playing the characters ‘Homestead’ and ‘Pinkerton’ (just as they had on Broadway). The show was so successful that they were invited to play at Buckingham Palace at a party held for the ninth birthday of the King’s eldest grandson, David, who later became King Edward VIII and then the Duke of Windsor.

|

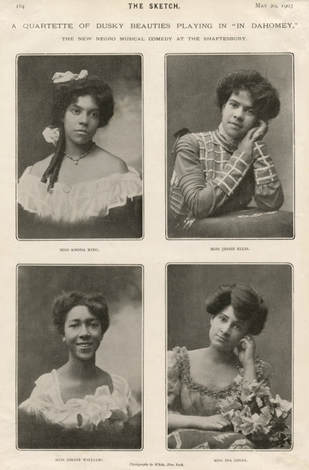

Aida Overton Walker, a leading member of the cast, considered presenting refined African American characters on the stage to be important political work. [11] As part of this concern, she made sure that the female performers were dressed in the most elegant manner. Audiences, expecting the women to be dressed in bandanas and "plantation fashions", were amazed to see them arrayed in the latest creations from Paris.

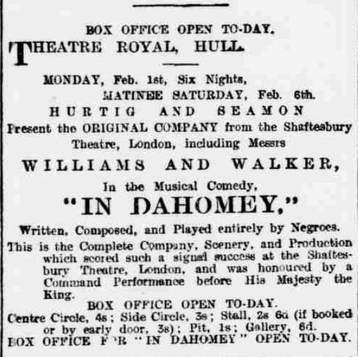

Coming to Hull

Hull was the first provincial town that In Dahomey played, and the Hull Daily Mail stated that the town was "privileged" to have it here for six nights from 1st February 1904, at the Theatre Royal. [12] The Mail referred to the musical as a "sensation" and claimed that the musical style and dances had "not [been] seen before in Hull." [13]

Hull was the first provincial town that In Dahomey played, and the Hull Daily Mail stated that the town was "privileged" to have it here for six nights from 1st February 1904, at the Theatre Royal. [12] The Mail referred to the musical as a "sensation" and claimed that the musical style and dances had "not [been] seen before in Hull." [13]

|

The crowd were particularly thrilled by the women in the show who were acclaimed as "remarkable" and "phenomenal" for their "bewildering gyrations" and "lightning-like" feet. [14] However, some of the language used by the Hull Daily Mail does remind us of the context of the time. The original advertisement sells the musical based on the fact it is "played entirely by REAL NEGROES", with the unique selling point of the show seeming to be the novelty of seeing the African Americans rather than visiting for the story itself. This is reinforced by the negative connotations in the choice of words such as "barbarically scored" to describe the music of Marion Cook. [15] It seems, even the comedic genius of Shipp could not break free from the constraints of the time, with people watching the musical with curiosity and commenting on the "unconventional" music. [16]

Nevertheless, the musical sparked "considerable interest" and sold out all six nights, with the Beverley and East Riding Recorder claiming the musical "exceeded all expectations" as a "quite unique" piece of theatre. [17]

|

After a year in Britain, the original cast of In Dahomey returned to America, re-opening the show in New York on 27th August 1904, before embarking on a major tour of the USA. Meanwhile, the No. 2 American company, which starred Dan Hart, Charles Avery and Stella Hart, came to Britain. This second production soon made its way to Hull, appearing at the Grand Theatre for a week from 15th August, where it was received with as much acclaim as the version performed by the original cast. [18]

|

Music

The musical talent of Will Marion Cook cannot be underestimated. A violinist who "studied music all his life", Cook created a score that will never be forgotten by history. [19] But, Cook was not the only contributor to the impressive score of In Dahomey. Benjamin L. Shook, Cecil Mack, Alex Rogers and eight other named composers and lyricists worked together to create the thirteen musical numbers in the play. [20] The music shares a vaudevillian ragtime style which serves to strike an audience with African American culture from the offset. There is an encapsulation of both vaudevillian syncopation and classic early-20th century Broadway musical style which uniquely represents the assimilation of African Americans into White American culture, thus creating an altogether new identity for the American people. The significance of the musical score can be represented through the fact that many of In Dahomey’s songs have been performed in other vaudevillian Broadway shows such as Brown-skin Baby Mine, My Castle on the Nile, and When It’s All Goin’ Out and Nothin’ Comin’ In. [21]

The company were heralded for their voices, with the Hull Daily Mail stating that their tone was "extraordinary" and "astonishing". [22]

|

Cakewalk

One reason so many people loved In Dahomey was due to the cakewalk. However, there was no cakewalk in the original Broadway production, nor was it in the earliest shows in England. It was introduced by the management in the middle of the 1903 season in London, because British audiences expected it. [23] Historically, a cakewalk is a dance contest in which African Americans would compete to win a cake for a prize. Alexander refers to the cakewalk as the "most memorable legacy" of In Dahomey and states that the dance had all audiences "leaping to their feet." [24]

One reason so many people loved In Dahomey was due to the cakewalk. However, there was no cakewalk in the original Broadway production, nor was it in the earliest shows in England. It was introduced by the management in the middle of the 1903 season in London, because British audiences expected it. [23] Historically, a cakewalk is a dance contest in which African Americans would compete to win a cake for a prize. Alexander refers to the cakewalk as the "most memorable legacy" of In Dahomey and states that the dance had all audiences "leaping to their feet." [24]

This was certainly the case in Hull, the Hull Daily Mail recalls the audience "admiring" the dance, which was held on "a very elaborate scale." They state that "cheer after cheer" was had for each couple and their respective efforts to secure the cake. [25]

The people of Hull saw the experience of seeing a cakewalk as a "treat" and claimed that the dancer that did win the cake "danced in a way almost beyond belief." [26] The taste of African American culture that the cakewalk brought to Britain really proved to be a hit.

Comedy Stylings of Williams and Walker

Williams and Walker were received with great acclaim in Hull, with the Hull Daily Mail claiming that "the extravagances of this engaging pair kept the theatre ringing with laughter." [27] The two men were iconic at the time and performed in every performance over the four years of touring that the original cast of In Dahomey completed around the US and the UK. The amount of publicity they received for their part in the musical was remarkable, with the pair proceeding to produce two more musicals as the same act. These musicals, Williams and Walker in Abyssinia and Walker and Williams in Bandana Land, were both successful, though neither could compare to the response In Dahomey received. [28]

Williams and Walker were received with great acclaim in Hull, with the Hull Daily Mail claiming that "the extravagances of this engaging pair kept the theatre ringing with laughter." [27] The two men were iconic at the time and performed in every performance over the four years of touring that the original cast of In Dahomey completed around the US and the UK. The amount of publicity they received for their part in the musical was remarkable, with the pair proceeding to produce two more musicals as the same act. These musicals, Williams and Walker in Abyssinia and Walker and Williams in Bandana Land, were both successful, though neither could compare to the response In Dahomey received. [28]

Final Thoughts

Those fortunate enough to have watched In Dahomey really did experience something extraordinary, and something that had certainly never been seen before. When Will Marion Cook stated that music would be part of the "salvation of the negro race" he may well have been right. [29]

1903 saw the continuation of the struggles for African American civil rights and justices in Britain and America. Following the musical tour, the British media claimed that something had to be done about the "colour line" in London with various legal action made to reverse bans of Blacks from patronising certain places of the city.

Those fortunate enough to have watched In Dahomey really did experience something extraordinary, and something that had certainly never been seen before. When Will Marion Cook stated that music would be part of the "salvation of the negro race" he may well have been right. [29]

1903 saw the continuation of the struggles for African American civil rights and justices in Britain and America. Following the musical tour, the British media claimed that something had to be done about the "colour line" in London with various legal action made to reverse bans of Blacks from patronising certain places of the city.

A revival of the musical graced Broadway from 23rd June 1999, with a new script created that was "inspired by characters and songs from the three-act musical comedy." This revival has ensured that the legacy of In Dahomey lives on in modern musical culture. [30]

In Dahomey was daring and new for the time. Shipp and Cook took a huge risk when they decided to create the first African American musical on Broadway, but it certainly paid off with the cast, producers and directors (Hurtig and Seaman) becoming very "rich and prominent" due to their "considerable success." [31]

Footnotes

- [1] Hull Daily Mail, 12th August 1904, p.5.

- [2] Unknown author. (2017) In Dahomey. Available here. Last accessed 2nd December 2017.

- [3] Shaftesbury Theatre (Mid-June 1903). “In Dahomey” Programme. London: G. Harmsworth & Co. Printers. Available on Jeffery Green’s website.

- [4] S. Walker (2013). ‘In Dahomey’, First All-African-American musical, opens on Broadway. 18th February 1903. Available here. Last accessed 2nd December 2017.

- [5] J. Noordermeer. (10th October 2017). Swing Along: Broadway opens new doors. Available here. Last accessed 5th December 2017.

- [6] Ibid.

- [7] Z. Alexander (1987). ‘Black Entertainers’, in The Edwardian Era, edited by J. Beckett and D. Cherry, Phaidon Press and Barbican Art Gallery, p.45.

- [8] Ibid, p.46.

- [9] Quoted without reference in Z. Alexander (1987) ‘Black Entertainers’, in The Edwardian Era, edited by J. Beckett and D. Cherry, Phaidon Press and Barbican Art Gallery, p.46.

- [10] Z. Alexander (1987). ‘Black Entertainers’, in The Edwardian Era, edited by J. Beckett and D. Cherry, Phaidon Press and Barbican Art Gallery, p.46.

- [11] Aida Overton Walker. Available here. Last accessed 5th December 2017. [This is a very interesting article about Aida Overton Walker’s career.]

- [12] Hull Daily Mail, 22th January 1904, p.5.

- [13] Hull Daily Mail, 2nd February 1904, p.4.

- [14] Ibid.

- [15] Hull Daily Mail, 17th August 1904, p.2; Hull Daily Mail, 2nd February 1904, p.4.

- [16] Hull Daily Mail, 2nd February 1904, p.4.

- [17] Beverley and East Riding Recorder, 6th February 1904, p.5.

- [18] Hull Daily Mail, 16th August 1904, p.4.

- [19] Hull Daily Mail, 12th August 1904, p.5.

- [20] Unknown author (2017). In Dahomey. Available here. Last accessed 2nd December 2017.

- [21] T. L. Riis (ed.) (1996). The Music and Scripts of “In Dahomey”, A-R Editions, p.xxix.

- [22] Hull Daily Mail, 16th August 1904, p.4.

- [23] Jeffrey Green, “In Dahomey”, London – 1903. Available on Jeffrey Green's website. Last accessed 6th December 2017.

- [24] Z. Alexander (1987). ‘Black Entertainers’, in The Edwardian Era, edited by J. Beckett and D. Cherry, Phaidon Press and Barbican Art Gallery, p.46.

- [25] Hull Daily Mail, 16th August 1904, p.4.

- [26] Hull Daily Mail, 2nd February 1904, p.4.

- [27] Ibid.

- [28] E. Southern (1997). The Music of Black Americans: A History, W.W. Norton & Company, p.222.

- [29] Hull Daily Mail, 12th August 1904, p.5.

- [30] K. Jones (1999). First Legit African-American Musical, In Dahomey, Inspires New Version in NYC June 23-July 25. Available on the Playbill website. Last accessed 2nd December 2017.

- [31] R.E. Lotz (1997). Black People: Entertainers of African Descent in Europe and Germany, p.94.