By Audrey Dewjee

How, why, and exactly when James Edward Philadelphia Moore arrived in Scarborough is a mystery. He appears on the census of 1901, aged 26, a flower seller, living in William Street. His birthplace is stated as South Carolina and it is noted that he is a naturalised British Subject, although I have been unable to find any record to confirm this. James Moore is head of the household and the only other occupant is Ada M. Lewis aged 31, born in Doncaster and listed as his housekeeper. However, Moore had arrived in Scarborough at least five or six years previously.

I first heard of him about 30 years ago when a fellow researcher in Scarborough Reference Library told me of his existence. She was something of a local history expert and, when I explained that I was looking for information about people of African or Asian descent in Scarborough, she mentioned that a flower seller by the name of James Philadelphia Moore had been reported in the local newspaper from time to time for being drunk and disorderly.

Trying to discover more about him, I checked the 1891 census – without success, but I did find Ada Lewis. She was aged 24, married and living in Hope Street with her husband, John T. Lewis, a firewood dealer aged 33, born in Africa. John Thomas Lewis and Ada Mary Wilson had married at St. Mary’s Church, Scarborough on 3 January, 1889.

Trying to discover more about him, I checked the 1891 census – without success, but I did find Ada Lewis. She was aged 24, married and living in Hope Street with her husband, John T. Lewis, a firewood dealer aged 33, born in Africa. John Thomas Lewis and Ada Mary Wilson had married at St. Mary’s Church, Scarborough on 3 January, 1889.

|

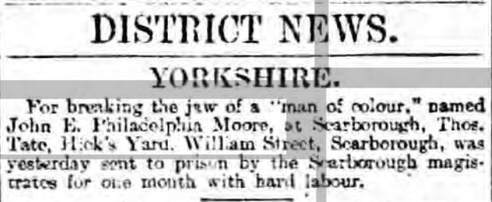

Unable to search Scarborough newspapers because they are not online, I was surprised to find Moore mentioned in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph. On 14 December 1895, under the heading “District News Yorkshire”, the paper reported that Thomas Tate of Hick’s Yard, William Street, had been sent to prison for one month with hard labour by Scarborough magistrates, for breaking the jaw of a “man of colour” named John [sic] E. Philadelphia Moore.

Scarborough Library provided me with a copy of a fuller report which appeared in the Scarborough Evening News. On Friday 13 December, Scarborough Magistrates, under the chairmanship of Mr. W. Rowntree, heard the case in the police court.

|

P.C. Bolton gave evidence that on 1 December at 1 a.m. he was called to Hick’s Yard because of a disturbance between Moore and his wife. When he arrived, Moore was coming up the street with a coal-rake in his hand that his wife had thrown at him. Thomas Tate was in the Yard and P.C. Bolton told him to go away because he “had nothing to do with it” and Tate replied “I will do for the … before morning.” P.C. Bolton then put Tate out of the Yard, but he was still hanging about in William Street when the policeman left.

At five minutes to two, Moore went into the police station bleeding at the left side of his face and told the Sergeant that his jaw had been broken by a man named Tate, whereupon the Sergeant sent him straight to the hospital accompanied by a police officer.

Tate, who maintained he had never struck Moore, called two witnesses in his defence. Ann Cartwright said that she and Tate were “standing talking at the end of the passage, when all at once Moore screamed and ran down William Street shouting ‘Police’.” The Clerk of the Court asked her if she had seen Moore’s jaw broken and she answered “No, I did not.” Moore then asked her, “Did your husband come out with his coat off and say he was going to knock my head off?” “No” she replied.

The Clerk then enquired “Is this the wife of the defendant?” and when Moore said “Yes”, the Clerk explained that a wife was not allowed to give evidence in defence of her husband.[1] He then asked “How is it that your name is Ann Cartwright? Are you married to the defendant?” to which she replied that she was not, adding that Moore was not married to his wife either. Presumably this was because Ada was still married to John Lewis. Getting a divorce in Victorian times would have been virtually impossible because of the cost. Only the very rich would have that option and, even then, only on very limited grounds.

After Ann Cartwright’s admission that she was not legally married to Tate, the Clerk allowed Moore to continue questioning her. She denied that Tate had said he would “do” for Moore.

John Hunter, the second witness called by Tate, said that on Tuesday 3 December, he had been in the Black Lion Inn when Moore came in. He asserted that in reply to his questions, Moore said that he did not know who broke his jaw but he was going to blame Tate for it. Moore denied he had said this.

Clearly the magistrates disbelieved Tate and his witnesses. They considered the assault proved and sentenced him to a month’s imprisonment with hard labour in York Castle.

There may be a further glimpse of Moore in Osbert Sitwell’s memoirs, in which he mentions a “negro, known locally as ‘Snowball’, who limped with a pitiful exoticism through the winter streets, trying to sell flowers” at the turn of the century.[2] Did he manage to make a living as a flower seller? Possibly it wasn’t too hard in the summer when the town was full of visitors, but it can’t have been easy in the cold Yorkshire winter.

At five minutes to two, Moore went into the police station bleeding at the left side of his face and told the Sergeant that his jaw had been broken by a man named Tate, whereupon the Sergeant sent him straight to the hospital accompanied by a police officer.

Tate, who maintained he had never struck Moore, called two witnesses in his defence. Ann Cartwright said that she and Tate were “standing talking at the end of the passage, when all at once Moore screamed and ran down William Street shouting ‘Police’.” The Clerk of the Court asked her if she had seen Moore’s jaw broken and she answered “No, I did not.” Moore then asked her, “Did your husband come out with his coat off and say he was going to knock my head off?” “No” she replied.

The Clerk then enquired “Is this the wife of the defendant?” and when Moore said “Yes”, the Clerk explained that a wife was not allowed to give evidence in defence of her husband.[1] He then asked “How is it that your name is Ann Cartwright? Are you married to the defendant?” to which she replied that she was not, adding that Moore was not married to his wife either. Presumably this was because Ada was still married to John Lewis. Getting a divorce in Victorian times would have been virtually impossible because of the cost. Only the very rich would have that option and, even then, only on very limited grounds.

After Ann Cartwright’s admission that she was not legally married to Tate, the Clerk allowed Moore to continue questioning her. She denied that Tate had said he would “do” for Moore.

John Hunter, the second witness called by Tate, said that on Tuesday 3 December, he had been in the Black Lion Inn when Moore came in. He asserted that in reply to his questions, Moore said that he did not know who broke his jaw but he was going to blame Tate for it. Moore denied he had said this.

Clearly the magistrates disbelieved Tate and his witnesses. They considered the assault proved and sentenced him to a month’s imprisonment with hard labour in York Castle.

There may be a further glimpse of Moore in Osbert Sitwell’s memoirs, in which he mentions a “negro, known locally as ‘Snowball’, who limped with a pitiful exoticism through the winter streets, trying to sell flowers” at the turn of the century.[2] Did he manage to make a living as a flower seller? Possibly it wasn’t too hard in the summer when the town was full of visitors, but it can’t have been easy in the cold Yorkshire winter.

|

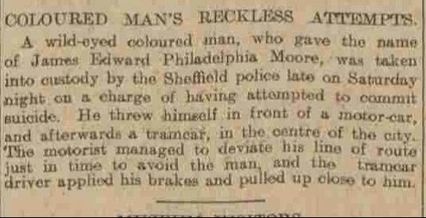

In 1908, James Moore appeared in the newspapers again when he caused a scandal in Sheffield by trying to commit suicide. Before the Suicide Act of 1961, committing suicide was a crime and anyone who attempted to do so and failed could be tried and sent to prison. There was a brief report in the Sheffield Evening Telegraph of 17 August.

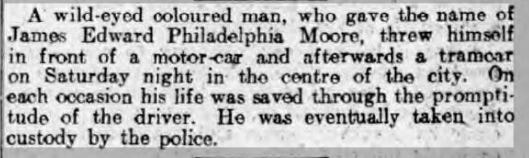

"A wild-eyed coloured man, who gave the name James Edward Philadelphia Moore, threw himself in front of a motor-car and afterwards a tramcar on Saturday night in the centre of the city. On each occasion his life was saved through the promptitude of the driver." |

In its report, the Sheffield Independent added the further information that Moore was “a stranger to Sheffield, having tramped into town on Thursday night.”

James Moore was eventually taken into custody by the police and over the next three days his story was revealed in the newspapers. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph of 18 August reported:

James Moore was eventually taken into custody by the police and over the next three days his story was revealed in the newspapers. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph of 18 August reported:

|

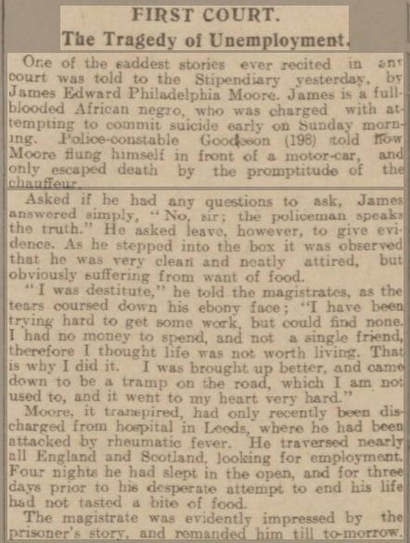

FIRST COURT.

The Tragedy of Unemployment. One of the saddest stories ever recited in any court was told to the Stipendiary yesterday, by James Edward Philadelphia Moore. James is a full-blooded African negro, who was charged with attempting to commit suicide early on Sunday morning. Police Constable Goodeson (198) told how Moore flung himself in front of a motor-car, and only escaped death by the promptitude of the chauffeur.

Asked if he had any questions to ask, James answered simply, “No, sir; the policeman speaks the truth.” He asked leave, however, to give evidence. As he stepped into the box it was observed that he was very clean and neatly attired, but obviously suffering from want of food. “I was destitute,” he told the magistrates, as the tears coursed down his ebony face; “I have been trying hard to get some work, but could find none. I had no money to spend, and not a single friend, therefore I thought life was not worth living. That is why I did it. I was brought up better, and came down to be a tramp on the road, which I am not used to and it went to my heart very hard.” |

|

Moore it transpired, had only recently been discharged from hospital in Leeds, where he had been attacked by rheumatic fever. He traversed nearly all England and Scotland, looking for employment. Four nights he had slept in the open, and for three days prior to his desperate attempt to end his life had not tasted a bite of food.

The Magistrate was evidently impressed by the prisoner’s story, and remanded him until to-morrow. |

|

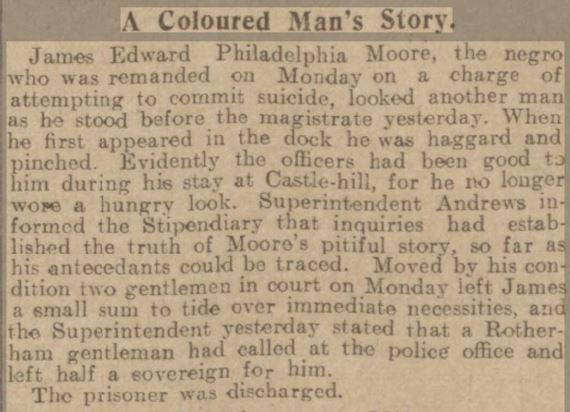

The following day, the same paper (see left) reported that Moore, who had been “haggard and pinched” when he first appeared in court, “looked another man… Evidently the officers had been good to him during his stay at Castle-hill, for he no longer wore a hungry look.” Superintendent Andrews informed the magistrate that enquiries had established the truth of Moore’s pitiful story, as far as it could be traced. “Moved by his condition two gentlemen in court on Monday had left James a small sum to tide over immediate necessities” and the Superintendent further stated that a Rotherham gentleman had called at the police office and left half a sovereign for him.

Moore was discharged. Hopefully, the regular meals he had had while in custody and the kindness of his three well-wishers gave him the strength to carry on. |

It is interesting to note how the attitude of the newspaper reporters changed over the week. Their initial sensational description of the “wild-eyed coloured man” changed to feelings of sympathy when they heard him tell his story.

So far I have been unable to find any further information about James Moore, although the record of the death of a James P. Moore aged 49, in Liverpool in 1927 may refer to him. I sincerely hope that life treated him more kindly in his later years. His story illustrates just how difficult life in this country could be for the unemployed and other poor people in the days before the welfare state, and probably more so, if they were Black.

So far I have been unable to find any further information about James Moore, although the record of the death of a James P. Moore aged 49, in Liverpool in 1927 may refer to him. I sincerely hope that life treated him more kindly in his later years. His story illustrates just how difficult life in this country could be for the unemployed and other poor people in the days before the welfare state, and probably more so, if they were Black.

Footnotes

[1] Three years later, the Criminal Evidence Act of 1898 enabled spouses to give evidence for the defence.

[2] O. Sitwell, The Scarlet Tree (London: Macmillan; Reprint Society, 1951), p.287.

[1] Three years later, the Criminal Evidence Act of 1898 enabled spouses to give evidence for the defence.

[2] O. Sitwell, The Scarlet Tree (London: Macmillan; Reprint Society, 1951), p.287.