In 1983, a few weeks before she died of cancer, my mother told me that she had been brought up in a children’s home. As we were very close, this came as a complete surprise because she had always led me to believe that she had been brought up by her grandmother. When I asked her to elaborate she wouldn’t, but said she’d never told me before as she thought it would upset me.

Eight years later, I was appearing at the Theatre Royal in York. An article appeared in the local newspaper and members of my mother’s family contacted me. Through them I discovered that there was more to her life than I had ever imagined. Not least, I began to discover what it must have been like to grow up as a mixed-race, illegitimate child in a Yorkshire village during the early part of the last century. I also began to reconsider the history of Black people in Britain. Historically, it is generally believed that Black people arrived in Britain in the 1950s yet, as a child growing up in London during the 50s, all the ‘coloured’ people I knew had been born here.

This is my mother's story.

Eight years later, I was appearing at the Theatre Royal in York. An article appeared in the local newspaper and members of my mother’s family contacted me. Through them I discovered that there was more to her life than I had ever imagined. Not least, I began to discover what it must have been like to grow up as a mixed-race, illegitimate child in a Yorkshire village during the early part of the last century. I also began to reconsider the history of Black people in Britain. Historically, it is generally believed that Black people arrived in Britain in the 1950s yet, as a child growing up in London during the 50s, all the ‘coloured’ people I knew had been born here.

This is my mother's story.

|

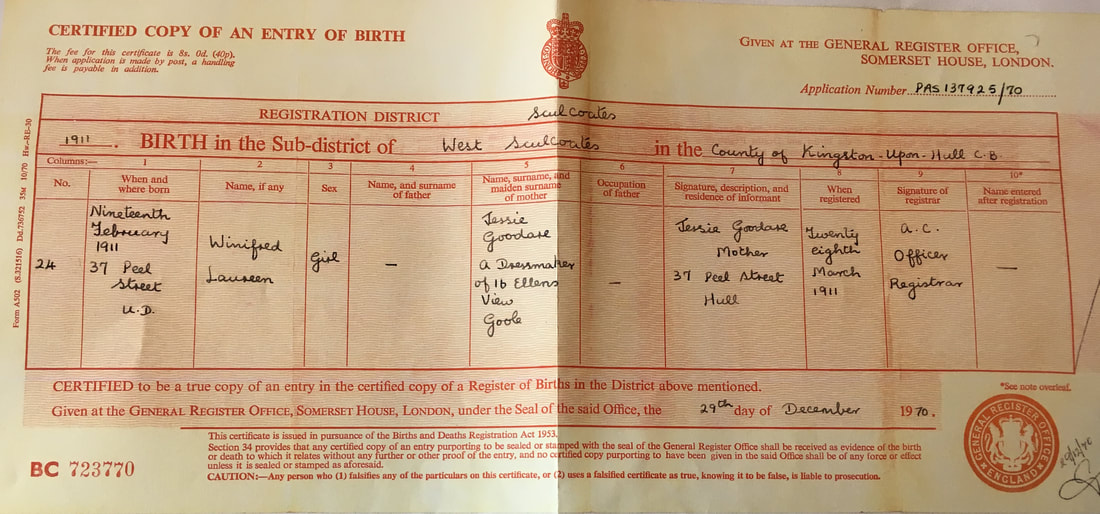

Winifred Laureen Goodare was born 19 February 1911 at 37 Peel Street, Hull and was baptised at St Paul’s Church on 23 March 1911. Her mother, Jessie Goodare, was 22 years old and lived at 16 Ellen’s View, Goole. According to the census Jessie was a variety artist, earning 4/- (shillings) a week. Laureen’s father was unknown. There is little mention of him in her file from the Children’s Society, although at one point he is referred to as “probably an African.”

On 30 March 1911 she was admitted to All Saints Nursery College, Harrogate. Laureen was described as healthy, good tempered and attractive with nice habits and as having a foreign appearance and being very dark. She was accepted by the Society on 14 August 1912 and was boarded out with a foster mother, Mrs Mary Dinsdale of Burnt Yates, Harrogate. |

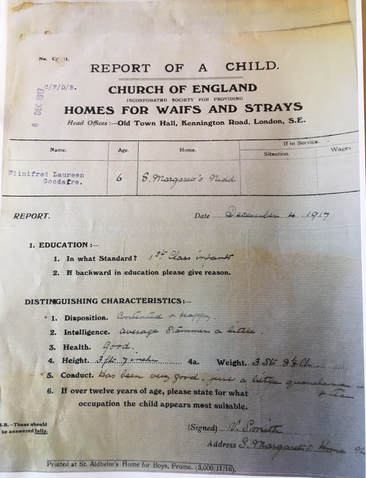

In January 1917 Laureen was removed from Mary Dinsdale’s care as the foster mother felt that the responsibility of looking after a young child was becoming too much for her in her old age. Laureen went to live with another foster mother who lived nearby but missed Mary Dinsdale and repeatedly ran back to her. As a result it was decided to remove her to St Margaret’s home, Nidd and she was admitted on 14 February 1917. A letter of 26 February 1917 describes her as happy and settled (see left).

It was common practice for the supporters of the Society to sponsor named children. They would often select a child from a group of candidates presented to them by the Society and would receive chatty reports of their protégee’s progress as well as a photograph. In May 1922 Laureen was the beneficiary of money donated by Mrs Carrie Bennett of King’s Bromley, Lichfield. She had lost her little girl in December 1919 and sent money on the anniversary of the child’s birthday in April. Mrs Bennett could not guarantee regular donations but was anxious to help Laureen as much as she could. She included extra donations to help buy the child nourishing food as she was recovering from scarlet fever in May 1922. Laureen had spent over a month in an Isolation Hospital returning to St Margaret’s on 1 June 1922. When the supervisor of St Margaret’s was writing to the Society authorities about the sponsor money in May 1922 she described Laureen as a “fascinating clever pickle and a clean, pure, lovable girl.” On 3 August 1926 she left St Margaret’s to go into service with Mrs Gethin, Cayton Hall, South Stainley near Harrogate. Her wages were £18 per year. |

In January 1930 Laureen was back at St Margaret’s helping in the kitchen. A letter date 24 January from Mr J H Hayers, the Secretary of the Ripon-Wakefield and Bradford Branch to Revd. A J Westcott, the Secretary of the Waifs and Strays Society stated that she was determined to join a coloured troupe of dancers. Laureen had had difficulty in Yorkshire with the public making remarks about her colour and this influenced her decision to seek employment elsewhere in the country.

On 14 April 1930 Mr Hayers reported that Laureen had communicated with a Mons Paul, an illusionist, and had made arrangements to work as his assistant in Bognor and then for a season at Morecambe. After that she travelled with him to Cork, Ireland.

Having fulfilled her engagements with the troupe, Laureen moved to London where, in 1931, she worked in a coffee shop in Aldgate. Later that year she took up service again for a Jewish family (The Kauffmans) in North West London, remaining in contact with them until the 60s. As a child I remember that she would cook the most delicious Jewish food, which she had probably learnt from them.

On 14 April 1930 Mr Hayers reported that Laureen had communicated with a Mons Paul, an illusionist, and had made arrangements to work as his assistant in Bognor and then for a season at Morecambe. After that she travelled with him to Cork, Ireland.

Having fulfilled her engagements with the troupe, Laureen moved to London where, in 1931, she worked in a coffee shop in Aldgate. Later that year she took up service again for a Jewish family (The Kauffmans) in North West London, remaining in contact with them until the 60s. As a child I remember that she would cook the most delicious Jewish food, which she had probably learnt from them.

|

Determined to enter show business, Laureen studied tap in London under Buddy Bradley a well known American dancer and choreographer and started working on ‘coloured’ shows as a chorus girl touring around the UK. Once, when she was in a show in Cork, she was approached by a very old woman who said “Jesus, I haven’t seen one of my own kind for years.”

Laureen was based in London and started working at the Shim Sham Club. The Shim Sham was a popular night club in Wardour Street, Soho. It was frequented by the likes of Edwina Mountbatten, the Italian boxer Primo Carnera and musicians playing there included Fats Waller, Nat Gonella and Garland Wilson. Laureen worked there as cigarette girl and also danced in cabaret as one of the four ‘Chocolate Drops.’ She told me that once when people got up to dance, they would stub out their cigarettes, even if they had only taken a couple of puffs. Laureen would collect them and on her way home would take them to the homeless people who congregated under Hungerford Bridge. It was whilst working at the Shim Sham that she met the conductor Constant Lambert. They began a long affair and friendship which lasted until his untimely death in 1951. During the war she volunteered as a Firewatcher and was based in Manchester Square, London. |

In 1944 she married Owen Oscar Sylvestre from Trinidad, a Flight Sergeant in the Air Force, who came to England to fight in the war. Owen had been awarded the DFM which was awarded to non-commissioned officers and men for exceptional valour, courage or devotion to duty while flying in active operations against the enemy.

|

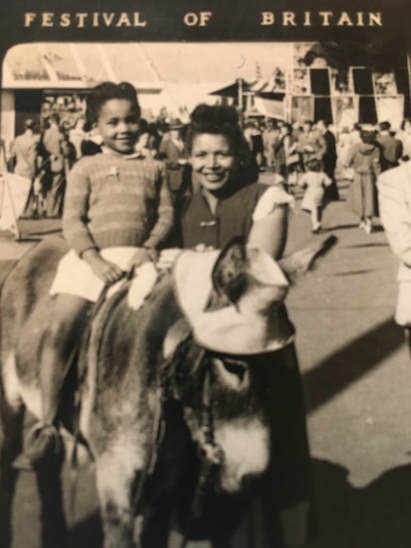

On 19 April 1945, she gave birth to a daughter. I was named Cleopatra Mary. Constant Lambert wrote to Laureen asking if he could be my godfather, which indeed he became.

Laureen's marriage to Owen was somewhat rocky. Like many other service personnel from what was then known as, 'the Colonies', Owen was unable to find employment with a commercial airline company, so he enrolled at the LSE (London School of Economics). However, he developed a passion for gambling which eventually destroyed the marriage and he and Laureen divorced in 1955. Throughout the marriage Laureen worked in various jobs from catering at Bridge parties to cleaning, and when I started school in order to be with her during the holidays, she became an artist’s model working in various Art’s Schools such as The Slade, Sir John Cass, Chelsea and Guildford. Although having left formal schooling at an early age, she was exceptionally well read and attended adult education classes throughout her life. She studied French, recorder, upholstery, pottery and in her 60s took on a new challenge of silver jewellery making. By then I had begun my career as an actress and Laureen’s jewellery proved to be very popular- getting commissions from my colleagues both at The National Theatre and Young Vic.

|

|

In 1960 Laureen developed breast cancer, and, worried that Cleo would be left orphaned, wrote to the Registrar in Hull trying to find any members of the Goodare family. As a result she managed to contact a brother of Jessie (her mother). He was living in Goole with his wife and family and invited us to stay. We received a warm Yorkshire reception and Laureen met many cousins for the first time. Through them she learnt that her mother (my grandmother) had married, then emigrated to America where she set up a dancing school. She never had another child and although she would send money back to England for her nieces and nephews, she never remembered her own daughter Laureen. It was said that one of her dance pupils was Ginger Rogers, but we haven’t yet been able to prove it.

Laureen’s culinary skills stayed with her. She would easily prepare a Chinese meal for 12 or more in the tiny kitchen of the council flat where we lived near Euston. As a teenager when I discovered a passion for the Blues and started going to music clubs, she would rustle up food for various ‘poor’ musician friends I brought home, including Brian Jones (of the Rolling Stones) and his girlfriend Linda, Mick Jagger and Long John Baldry amongst others. |

|

In 2014, Laureen’s granddaughter (my daughter) Zoe Palmer, won a seed commission to begin a piece based on Laureen’s life called Fosterling. This work-in-progress was performed at Ovalhouse Theatre in London to great acclaim and at some stage we hope it will have another life.

|

Laureen died on 3 January 1983 from cancer, aged 71. She never bore any malice or hatred towards her mother who rejected her, or the fact that she was bought up in a home. She had led a rich and creative life.