By Allison Edwards

Pablo Fanque, (born - William Darby), was the first Black English circus owner, becoming famous in Victorian Britain for his extraordinary shows. They remained the most popular for around 30 years, often having extended seasons – as in Hull, in September/October, 1846. He primarily performed in Yorkshire and Lancashire, though he also travelled to Scotland, Ireland and other parts of England. At one point, his circus was based in its own purpose-built auditorium in Manchester, capable of holding an audience of 3,000.[1]

Families flocked to his shows in their thousands, lured by exciting poster and newspaper advertisements, street parades and the stories told by those who had been held spellbound by what they had experienced. Pablo was extremely adept at conjuring together new ‘exotic’ names, acts and historical extravaganzas, which could transport poor people out of what many experienced as drab, hardworking lives into a world of imagination, colour, dangerous feats of courage, expertise and sheer fun! His shows appealed equally to those of the higher classes.

|

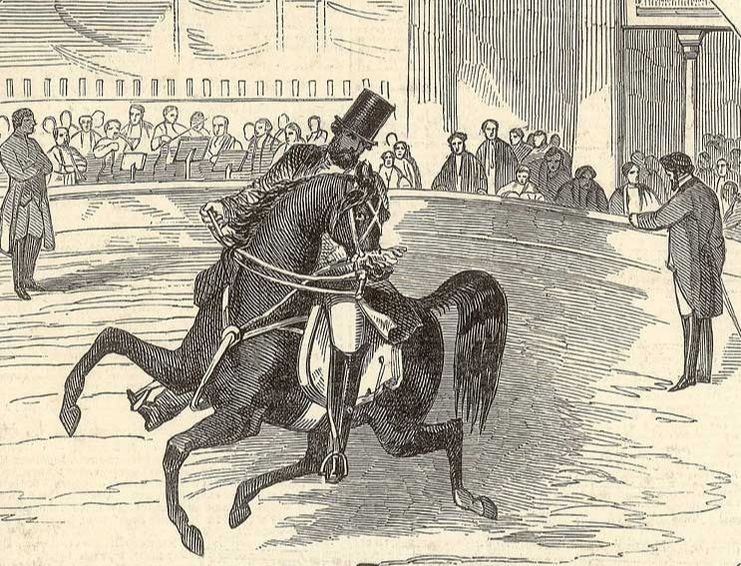

Fanque started out as an extremely gifted tight rope walker and acrobat and a highly respected and admired equestrian. Over the years he built up a fine stud of horses and ponies, at least one of which was purchased from Queen Victoria’s stables.[2] He was an outstanding trainer of horses and is said to have ridden out with the Duke of Wellington in Hyde Park.

His feats of horsemanship were renowned – particularly with his favourite black mare, Beda, with whom he performed in front of the Queen and Royal Family at Astley’s famous Amphitheatre, on Westminster Bridge Road, London, in 1847. His most remarkable feat, according to the circus historian George Speaight, was leaping on horseback over a coach placed lengthways with a pair of horses in the shafts, and through a military drum at the same time.[3] Nobody appears to know where his ‘assumed’ name of Pablo Fanque originated. He was born William Darby in St. Andrew’s Workhouse, Norwich. His date of birth is now known to have been March 30, 1810, (rather than in 1796, as was originally believed).[4] The |

confusion arose because an earlier baby named William, had been born to his parents – John Darby and Mary Stamp – on February 28, 1896, but had died some 14 months later. The baptisms of both these babies and other siblings are recorded at St Stephen’s, Norwich, together with their parents’ marriage, (in 1791) and the burials of the first baby William and his sister, Mary Elizabeth, in 1797 and 1801, respectively. Information about Fanque’s father is speculative – he may have arrived in Norwich as a servant or have been formerly enslaved, and his mother’s origins are equally obscure.

William Darby became apprenticed to the circus proprietor, William Batty, around 1820, when he was about ten years old and the “Young Darby” appears to have made his first known appearance in Norwich, in 1821. He is recorded performing more than a decade later, in Nottingham in 1836, where he was described as Pablo Fanque, a ‘negro rope-dancer’.[5]

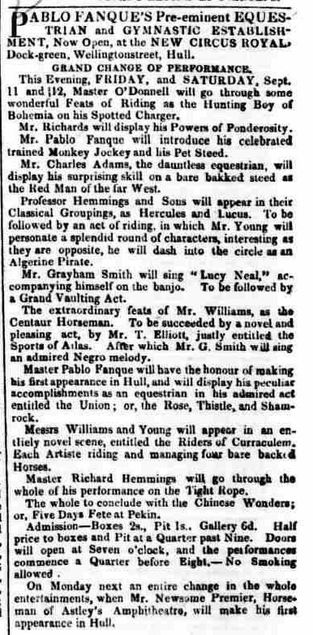

Ten years later, he made his first appearance in Hull. Pablo Fanque’s Pre-eminent Equestrian and Gymnastic Establishment was advertised, as ‘now being open’, at the New Circus Royal, Dock-green, Wellington-street, Hull.[6] Fanque’s ‘Establishment’ must have been extremely popular in the city, as it remained performing there for a month, through September and into October. The people of Hull were clearly in for a treat, as can be seen from the acts listed on Pablo’s advertisement below:

Ten years later, he made his first appearance in Hull. Pablo Fanque’s Pre-eminent Equestrian and Gymnastic Establishment was advertised, as ‘now being open’, at the New Circus Royal, Dock-green, Wellington-street, Hull.[6] Fanque’s ‘Establishment’ must have been extremely popular in the city, as it remained performing there for a month, through September and into October. The people of Hull were clearly in for a treat, as can be seen from the acts listed on Pablo’s advertisement below:

|

The show must have been hard to resist – it all sounded so exciting. The people of Hull could be transported in their imagination around the world and into the past, to Bohemia, the American West, Ancient Greece and China and all for the prices of Boxes 2 shillings, Pit 1 shilling, Gallery 6d. Customers could also be admitted for ‘half price to boxes and Pit at a Quarter past nine’.

On September 25, he had a benefit for Mr. Williams, ‘The Centaur Horseman’.[7] In those days, there was no NHS, no Welfare State with unemployment benefits, pensions and disability support if you had a terrible accident – not an uncommon occurrence in circuses in those days – so such benefits were frequently held and Pablo held one for himself, at which ‘the whole of the stud appeared in the ring at the same time’.[8] Over the years Fanque had ‘made his way’ and built up his own establishment. After leaving Mr. Batty, he joined the establishment of the late Mr. Ducrow, and remained with him for some time. He again joined Mr. Batty; in 1841, he began business on his own account, with two horses, and has assembled a fine stud of horses and ponies at his establishment at Wigan, in Lancashire, in which county Mr. Pablo is well known, and a great favourite.[9] |

Although he was a great self-publicist, Mike Dash writes of Fanque that:

One reason for Fanque’s success that goes unremarked in the circus histories is his keen appreciation of the importance of advertising. Among the advantages that his circus enjoyed over its numerous rivals was that it enjoyed the services of Edward Sheldon, a pioneer in the art of billposting whose family would go on to build the biggest advertising business in Britain by 1900. Fanque seems to have been among the first to recognise Sheldon’s genius, hiring him when he was just 17. Sheldon spent the next three years as Pablo’s advance man, advertising the imminent arrival of the circus as it moved from town to town.[10]

One reason for Fanque’s success that goes unremarked in the circus histories is his keen appreciation of the importance of advertising. Among the advantages that his circus enjoyed over its numerous rivals was that it enjoyed the services of Edward Sheldon, a pioneer in the art of billposting whose family would go on to build the biggest advertising business in Britain by 1900. Fanque seems to have been among the first to recognise Sheldon’s genius, hiring him when he was just 17. Sheldon spent the next three years as Pablo’s advance man, advertising the imminent arrival of the circus as it moved from town to town.[10]

In addition to such advertising, Fanque would organise a spectacular parade to announce his arrival in town. In Hull he drove ‘Twelve of his most beautiful Hanoverian and Arabian Steeds’ through the principal streets, accompanied by his ‘celebrated Brass Band’. He was known to drive fourteen horses in hand through the streets in some places, as he did in Manchester the following year.

The local paper publicised his return visits to Hull on a number of occasions over the years. In June 1847, he was appearing at Tourniaire’s Royal Amphitheatre, in Paragon Street, this time, not with his own establishment:

Mr Tourniaire anxious to meet with continuance of patronage, respectfully announces that he has, at very great expense, engaged, (to give brilliancy to the termination of the Season), the celebrated MONS. PABLO FANQUE, who will appear each EVENING in his admired performance on THE TIGHT ROPE.....NEW SCENES IN THE CIRCLE INCLUDING THE EQUESTRIAN FEATS OF MONS. PABLO FANQUE and a COMIC VAUDEVILLE.[11]

The local paper publicised his return visits to Hull on a number of occasions over the years. In June 1847, he was appearing at Tourniaire’s Royal Amphitheatre, in Paragon Street, this time, not with his own establishment:

Mr Tourniaire anxious to meet with continuance of patronage, respectfully announces that he has, at very great expense, engaged, (to give brilliancy to the termination of the Season), the celebrated MONS. PABLO FANQUE, who will appear each EVENING in his admired performance on THE TIGHT ROPE.....NEW SCENES IN THE CIRCLE INCLUDING THE EQUESTRIAN FEATS OF MONS. PABLO FANQUE and a COMIC VAUDEVILLE.[11]

Five months later, Pablo returned to the Royal Amphitheatre (now renamed the Queen’s Theatre) – a building which was said to be one of the finest of its class in the country. His shows included his famous black Mare, ‘Beda’, and Mr. W.F. Wallett, ‘the celebrated Comedian and Clown’. They appeared in ‘a splendid Drama in three acts, called, “THE ARAB AND HIS STEED; or, THE PEARL OF THE EUPHRATES,”... as performed at Astley's amphitheatre 108 nights to crowded and brilliant audiences’.

What a wonderful home-coming for Fanque’s friend and clown, the celebrated William Frederick Wallett who was born in Hull in 1806, and what a treat for the Hull public, who had an opportunity to savour what London crowds had enjoyed.[12] Numerous performers – riders, clowns, and acrobats, including Pablo Fanque Junior, ‘the extraordinary tightrope walker’ – thrilled and entertained their audiences. The programmes, which Pablo changed frequently, included Shakespearean sketches and spectacles such as ‘the Fete of the Bronze Horse; or, the Jingling Jumpers of Pekin’.[13] On December 29 and New Year’s Day, 1848, Fanque offered daytime performances ‘for the accommodation of Children and Parties from the country who cannot make it convenient to attend the Evening’s entertainments’.

In March 1848, tragedy struck. Pablo’s first wife, Susannah Marlow, was killed in an accident during one of his circus performances.

What a wonderful home-coming for Fanque’s friend and clown, the celebrated William Frederick Wallett who was born in Hull in 1806, and what a treat for the Hull public, who had an opportunity to savour what London crowds had enjoyed.[12] Numerous performers – riders, clowns, and acrobats, including Pablo Fanque Junior, ‘the extraordinary tightrope walker’ – thrilled and entertained their audiences. The programmes, which Pablo changed frequently, included Shakespearean sketches and spectacles such as ‘the Fete of the Bronze Horse; or, the Jingling Jumpers of Pekin’.[13] On December 29 and New Year’s Day, 1848, Fanque offered daytime performances ‘for the accommodation of Children and Parties from the country who cannot make it convenient to attend the Evening’s entertainments’.

In March 1848, tragedy struck. Pablo’s first wife, Susannah Marlow, was killed in an accident during one of his circus performances.

The circus was held in an amphitheatre in King Charles Croft, Leeds, which Fanque had bought ‘as it stood’, it having been built previously for a rival circus proprietor, Charles Hengler. Some pit supports gave way under a packed crowd and collapsed into the lower gallery just as Pablo Fanque Junior was performing on the tightrope.

Mrs. Darby and Mrs. Wallett were both in the lobby at the time of the occurrence. They were both knocked down by the falling timber; two heavy planks fell upon the back part of the head and neck of Mrs. Darby, and killed her on the spot. Mrs Wallett, besides many others, received bruises and contusions, but the above was the only fatal accident.[14]

Mrs. Darby and Mrs. Wallett were both in the lobby at the time of the occurrence. They were both knocked down by the falling timber; two heavy planks fell upon the back part of the head and neck of Mrs. Darby, and killed her on the spot. Mrs Wallett, besides many others, received bruises and contusions, but the above was the only fatal accident.[14]

In all the panic and confusion, some immoral and heartless ‘chancer’ stole all the evening’s takings of more than £50.[15] Despite the tragedy, the show had to go on.

In June, 1848, Fanque married his second wife – Elizabeth Corker of Sheffield – a circus rider some twenty years his junior. Both wives and some children from both marriages performed in his circuses, notably Edward Charles, (1855-1937), who performed as ‘Ted Pablo’.

Pablo’s circus visited other parts of East Yorkshire, performing in Scarborough and Bridlington in August, 1855. At Bridlington the newspaper review noted that ‘two performances were given and the very capacious pavilion was crowded on both occasions…The horses and ponies were in capital condition, and greatly admired for the cleverness with which they performed their respective parts. The entertainment was highly creditable, and of course very satisfactory. The band is an excellent one…The company on Wednesday evening was one of the largest, if not the largest, ever seen here.’[16]

Fanque was to experience a particular low point in his career, in 1859, when he was mired in a bankruptcy hearing at the Leeds Court of Bankruptcy. Along with a number of other newspapers, the Hull Packet recorded on June 3, 1859, that the ‘certificate of William Darby popularly known as Pablo Fanque, an equestrian manager, was refused on the ground that he had given a fraudulent reference to a person named Battey, and that he had constructed a debt with a Mr. Myers by false and fraudulent representations.’ However his affairs were soon straightened out and he was back on the road again shortly afterwards.

Fanque’s circus was back in Scarborough, at the Rock Gardens, in March 1861, where Madame Salvi, ‘a daring wire walker’, had a ‘narrow escape for her life, at least her limbs’, due to strong gusts of winds which caused her to lose her balance. Clearly she had enormous courage, because the previous December, the Hull Packet had carried a story from the Preston Chronicle, entitled, ‘Fearful Scene at Pablo Fanque’s Circus’. Madame Salvi had been walking along a ‘thin twisted wire cable, stretching from the top of the circus (outside) to a block fixed a little above the front entrance to the establishment…when one of the ropes which held the wire at the top of the circus gave way’, throwing her off the wire. ‘In descending, however, she managed to catch the wire with one of her arms’, eventually securing it with her hands, ‘her body swinging in the air at full length.’ She was eventually rescued by some men with a ladder.[17]

The 1860s saw the beginning of the decline of Fanque’s circus, despite his clearly resilient and resourceful character. However, he returned to Hull in 1869 at the Queen’s Theatre as part of their Equestrian Season advertising his ‘World Renowned Monstre Circus Company at which Shouts of Admiration nightly greet the Great French Troupe….the Greatest Combination of Beauty, Grace and Daring Ever witnessed in any Equestrian Arena’.[18]

The Hull Packet reported, on March 19, 1869, that at the weekly meeting of the Sculcoates Union, ‘a letter was read from Pablo Fanque inviting the children of the Union to witness his circus at the Queen’s Theatre free of charge. The invitation was accepted and the customary vote of thanks passed.’ Fanque was renowned for his acts of generosity and frequently offered free seats to such children and gave donations for a variety of good causes. In Bradford, for instance, in July 1844, he donated £25 to the Independent Order of Oddfellows, for their Widows and Orphans Fund, and twice gave benefit performances for Bradford Infirmary, in March 1845 and in June, 1857.

However, Fanque’s fortune did not last and, within a couple of years, he was said to be living in great poverty in a room in the Britannia Inn, Stockport, with his wife and two sons – George and Ted – where he died on May 4, 1871. It was a sad end for such an extraordinary man, who rose from humble beginnings to reach the top of his profession in a career that lasted fifty years.

Pablo’s funeral was a spectacular occasion. His body was brought from Stockport by train and a great procession accompanied him to his resting place, watched by several thousand people. The hearse was preceded by a band playing the ‘Dead March’ from Saul. It was followed by Pablo’s favourite horse, Wallett, ‘partially draped in mourning trappings and led by a groom’, four mourning coaches, and several cabs and private vehicles. Pablo was buried with his first wife in Woodhouse Cemetery, Leeds. [19]

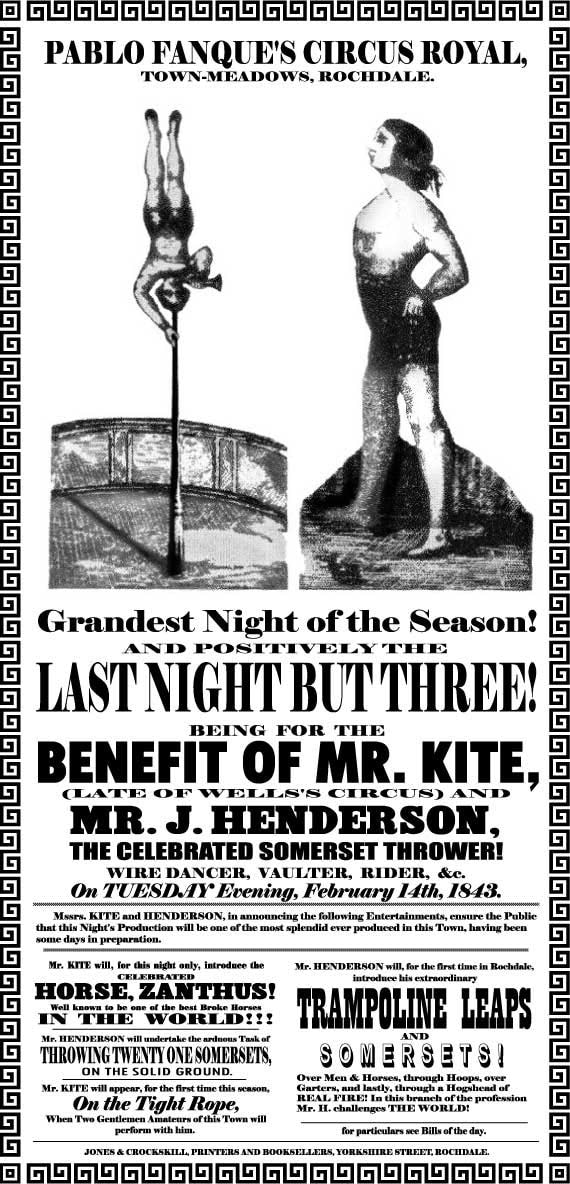

Pablo Fanque’s name had been almost forgotten until it became immortalised fifty years ago, on the Beatles’ album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band – in the song, ‘Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite’. The song’s words had been lifted by John Lennon from an advertising poster for Fanque’s Royal Circus in Rochdale, in 1843, which Lennon had spotted in an antique shop in Sevenoaks, Kent, (below).

In June, 1848, Fanque married his second wife – Elizabeth Corker of Sheffield – a circus rider some twenty years his junior. Both wives and some children from both marriages performed in his circuses, notably Edward Charles, (1855-1937), who performed as ‘Ted Pablo’.

Pablo’s circus visited other parts of East Yorkshire, performing in Scarborough and Bridlington in August, 1855. At Bridlington the newspaper review noted that ‘two performances were given and the very capacious pavilion was crowded on both occasions…The horses and ponies were in capital condition, and greatly admired for the cleverness with which they performed their respective parts. The entertainment was highly creditable, and of course very satisfactory. The band is an excellent one…The company on Wednesday evening was one of the largest, if not the largest, ever seen here.’[16]

Fanque was to experience a particular low point in his career, in 1859, when he was mired in a bankruptcy hearing at the Leeds Court of Bankruptcy. Along with a number of other newspapers, the Hull Packet recorded on June 3, 1859, that the ‘certificate of William Darby popularly known as Pablo Fanque, an equestrian manager, was refused on the ground that he had given a fraudulent reference to a person named Battey, and that he had constructed a debt with a Mr. Myers by false and fraudulent representations.’ However his affairs were soon straightened out and he was back on the road again shortly afterwards.

Fanque’s circus was back in Scarborough, at the Rock Gardens, in March 1861, where Madame Salvi, ‘a daring wire walker’, had a ‘narrow escape for her life, at least her limbs’, due to strong gusts of winds which caused her to lose her balance. Clearly she had enormous courage, because the previous December, the Hull Packet had carried a story from the Preston Chronicle, entitled, ‘Fearful Scene at Pablo Fanque’s Circus’. Madame Salvi had been walking along a ‘thin twisted wire cable, stretching from the top of the circus (outside) to a block fixed a little above the front entrance to the establishment…when one of the ropes which held the wire at the top of the circus gave way’, throwing her off the wire. ‘In descending, however, she managed to catch the wire with one of her arms’, eventually securing it with her hands, ‘her body swinging in the air at full length.’ She was eventually rescued by some men with a ladder.[17]

The 1860s saw the beginning of the decline of Fanque’s circus, despite his clearly resilient and resourceful character. However, he returned to Hull in 1869 at the Queen’s Theatre as part of their Equestrian Season advertising his ‘World Renowned Monstre Circus Company at which Shouts of Admiration nightly greet the Great French Troupe….the Greatest Combination of Beauty, Grace and Daring Ever witnessed in any Equestrian Arena’.[18]

The Hull Packet reported, on March 19, 1869, that at the weekly meeting of the Sculcoates Union, ‘a letter was read from Pablo Fanque inviting the children of the Union to witness his circus at the Queen’s Theatre free of charge. The invitation was accepted and the customary vote of thanks passed.’ Fanque was renowned for his acts of generosity and frequently offered free seats to such children and gave donations for a variety of good causes. In Bradford, for instance, in July 1844, he donated £25 to the Independent Order of Oddfellows, for their Widows and Orphans Fund, and twice gave benefit performances for Bradford Infirmary, in March 1845 and in June, 1857.

However, Fanque’s fortune did not last and, within a couple of years, he was said to be living in great poverty in a room in the Britannia Inn, Stockport, with his wife and two sons – George and Ted – where he died on May 4, 1871. It was a sad end for such an extraordinary man, who rose from humble beginnings to reach the top of his profession in a career that lasted fifty years.

Pablo’s funeral was a spectacular occasion. His body was brought from Stockport by train and a great procession accompanied him to his resting place, watched by several thousand people. The hearse was preceded by a band playing the ‘Dead March’ from Saul. It was followed by Pablo’s favourite horse, Wallett, ‘partially draped in mourning trappings and led by a groom’, four mourning coaches, and several cabs and private vehicles. Pablo was buried with his first wife in Woodhouse Cemetery, Leeds. [19]

Pablo Fanque’s name had been almost forgotten until it became immortalised fifty years ago, on the Beatles’ album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band – in the song, ‘Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite’. The song’s words had been lifted by John Lennon from an advertising poster for Fanque’s Royal Circus in Rochdale, in 1843, which Lennon had spotted in an antique shop in Sevenoaks, Kent, (below).

Footnotes

[1] Mike Dash, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/pablo-fanques-fair-71575787/ [accessed 09/07/2017]

[2] ibid

[3] A History of the Circus, George Speaight, The Tantivy Press, London, 1980.

[4] He was baptised in the Workhouse on April 1, 1810.

[5] Circus Life and Circus Celebrities, Thomas Frost, Chatto & Windus, London, 1881, p.97.

[6] Hull Packet, September 11, 1846, p.4.

[7] Hull Packet, September 25, 1846, p.1.

[8] Hull Packet, October 2, 1846, p.4.

[9] Illustrated London News, March 20, 1847, p.13.

[10] http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/pablo-fanques-fair-71575787/ [accessed 09/07/2017]

[11] Hull Packet, June 25, 1847, p.5.

[12] Hull Packet, November 26, 1847, p.4.

[13] Hull Packet, December 17, 1847, p.4.

[14] The Annals and History of Leeds, John Mayhall (comp.), Joseph Johnson, Leeds, 1861, p.555.

[15] Mike Dash, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/pablo-fanques-fair-71575787/

[16] Hull Packet, August 10, 1855, p.5.

[17] Hull Packet, December 14, 1860, p.3.

[18] Hull Packet, March 5, 1869, p.4.

[19] Now St. George’s Field, located within the campus of Leeds University.

[1] Mike Dash, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/pablo-fanques-fair-71575787/ [accessed 09/07/2017]

[2] ibid

[3] A History of the Circus, George Speaight, The Tantivy Press, London, 1980.

[4] He was baptised in the Workhouse on April 1, 1810.

[5] Circus Life and Circus Celebrities, Thomas Frost, Chatto & Windus, London, 1881, p.97.

[6] Hull Packet, September 11, 1846, p.4.

[7] Hull Packet, September 25, 1846, p.1.

[8] Hull Packet, October 2, 1846, p.4.

[9] Illustrated London News, March 20, 1847, p.13.

[10] http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/pablo-fanques-fair-71575787/ [accessed 09/07/2017]

[11] Hull Packet, June 25, 1847, p.5.

[12] Hull Packet, November 26, 1847, p.4.

[13] Hull Packet, December 17, 1847, p.4.

[14] The Annals and History of Leeds, John Mayhall (comp.), Joseph Johnson, Leeds, 1861, p.555.

[15] Mike Dash, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/pablo-fanques-fair-71575787/

[16] Hull Packet, August 10, 1855, p.5.

[17] Hull Packet, December 14, 1860, p.3.

[18] Hull Packet, March 5, 1869, p.4.

[19] Now St. George’s Field, located within the campus of Leeds University.