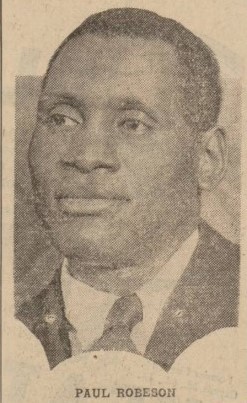

Paul Robeson was an athlete, film and stage actor, writer, singer, orator, lawyer and human rights activist. He was part of a generation of Black Americans who looked to prove their equality by unshackling the chains of their forbearers and reaching prominent positions in their careers. He visited Hull and East Yorkshire on several occasions between 1931 and 1960 performing concerts in front of his adoring fans.

Paul Leroy Robeson was born on 9 April 1898. He was the youngest child of Reverend William Drew and Maria Louisa Robeson.[1] As a liberated slave, his father was exceptionally proud of his African heritage and regularly preached about equality at Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church which was popularly known as the 'church for coloured people'.[2] From a very early age Robeson and his five siblings were exposed to the ideals of freedom, liberty and Civil Rights. However, they were born in an era of oppression, as Jim Crow laws enforced racial segregation and promoted racism.

Sadly, at the age of 6, Robeson’s mother died in a house fire. The family relocated to a neighbouring town before eventually settling in Somerville, New Jersey. Reverend Robeson was appointed pastor of St. Thomas A. M. E. Zion Church where he was an advocate of African American pride.[3] He instilled in his children the principles that no man was better or worse and they could be whatever they wanted to be if they worked hard enough. He also encouraged them to have strong self-esteem and to embrace their African heritage. However, being only one of two Black pupils at his school, Robeson encountered racial prejudice from a young age. This was not only from other children and their parents, but also from the principle of the school. Despite their protestations, Robeson played an active role in drama classes, and the glee club - where he discovered his baritone voice - and sports.

Sadly, at the age of 6, Robeson’s mother died in a house fire. The family relocated to a neighbouring town before eventually settling in Somerville, New Jersey. Reverend Robeson was appointed pastor of St. Thomas A. M. E. Zion Church where he was an advocate of African American pride.[3] He instilled in his children the principles that no man was better or worse and they could be whatever they wanted to be if they worked hard enough. He also encouraged them to have strong self-esteem and to embrace their African heritage. However, being only one of two Black pupils at his school, Robeson encountered racial prejudice from a young age. This was not only from other children and their parents, but also from the principle of the school. Despite their protestations, Robeson played an active role in drama classes, and the glee club - where he discovered his baritone voice - and sports.

|

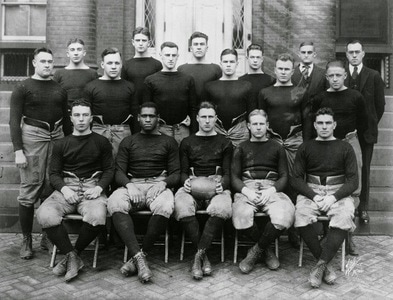

Robeson’s academic potential was realised in 1915 when he won a four-year scholarship to Rutgers College, New Jersey. Unfortunately, as a typically all-white college, Robeson was once again subjected to racism. Shortly after he enrolled at Rutgers, he tried out for the varsity football team. However, his fellow white classmates didn’t want Robeson playing alongside them. In later life Robeson recalled how the players were particularly aggressive towards him and it was not until he had lost his temper that he made the team.[4] He was an exceptional athlete and was shortly labelled as one of the best players in American football at the time. Despite high praise, this did not guarantee acceptance, and racism plagued Robeson’s social life. However, he found solace in friendship with other African Americans from nearby colleges.

|

On 17 May 1918 Robeson’s father died at the age of 73 and unfortunately never got to witness the extent of his son’s success. Although, saddened by his loss, Robeson continued to make a name for himself as an athlete. He received 12 varsity letters and was elected a member of Phi Beta Kappa Society.[5] Over the subsequent two years, Robeson won a series of prestigious awards for his academic and sporting achievements. The following year Robeson moved to New York and entered Columbia Law School. He gravitated to Harlem where he was already well known as the excellent American footballer from Rutgers. It was in Harlem that Robeson made his acting debut in Simon the Cyrenian.

In 1921, at the age of 23, Robeson met and married Eslanda Cardoza Goode. In the same year as his marriage, he played ‘African’ in the stage production of Taboo. This role enabled Robeson to take his first trip across the Atlantic to England where he met his lifelong friend Lawrence Brown. He returned to America in the Autumn to continue with his studies at Columbia. Two years later, he completed his law degree. While he searched for employment at a law firm, Robeson worked singing at Harlem’s famous Cotton Club.

Robeson eventually gained employment at an all-white law firm. However, racial prejudice severely hampered his career. Shortly after he accepted the position, he asked a secretary to take notes for him and her response was that she did not take orders from ‘niggers’.[6] In addition, it became increasingly apparent that none of the firm’s white clients would allow Robeson to represent them despite his intelligence, wit and ability. Robeson became disinterested in continuing with a career in which he could not rise to the top. Meanwhile, news of his excellent voice spread and Robeson was offered the lead roles in ‘All Gods Chillun got wings’ and ‘Emperor Jones' which he gladly accepted leaving his career as a lawyer behind. The former was a deeply controversial play. It explored racism within an interracial marriage as a representation of the problems within American society. The play deeply offended many white Americans particularly in the Southern States and on 5 May 1924, Robeson was threatened by the Ku Klux Klan for his leading role.[7]

In 1921, at the age of 23, Robeson met and married Eslanda Cardoza Goode. In the same year as his marriage, he played ‘African’ in the stage production of Taboo. This role enabled Robeson to take his first trip across the Atlantic to England where he met his lifelong friend Lawrence Brown. He returned to America in the Autumn to continue with his studies at Columbia. Two years later, he completed his law degree. While he searched for employment at a law firm, Robeson worked singing at Harlem’s famous Cotton Club.

Robeson eventually gained employment at an all-white law firm. However, racial prejudice severely hampered his career. Shortly after he accepted the position, he asked a secretary to take notes for him and her response was that she did not take orders from ‘niggers’.[6] In addition, it became increasingly apparent that none of the firm’s white clients would allow Robeson to represent them despite his intelligence, wit and ability. Robeson became disinterested in continuing with a career in which he could not rise to the top. Meanwhile, news of his excellent voice spread and Robeson was offered the lead roles in ‘All Gods Chillun got wings’ and ‘Emperor Jones' which he gladly accepted leaving his career as a lawyer behind. The former was a deeply controversial play. It explored racism within an interracial marriage as a representation of the problems within American society. The play deeply offended many white Americans particularly in the Southern States and on 5 May 1924, Robeson was threatened by the Ku Klux Klan for his leading role.[7]

The following year Robeson starred in several plays on both sides of the Atlantic. While in London he spent time with Lawrence Brown. It was in 1925, that the people of East Yorkshire would have first heard Robeson’s mesmerising voice as radio stations in the region began to play some of his songs. At 10.30 pm on 30 October 1925, listeners in Hull tuned in to hear Robeson sing ‘Negro Spirituals.’[8]

Throughout 1926 Robeson travelled across America singing for the hundreds of people who had gathered to hear his voice. In the Autumn, he accepted the lead role in the Black Boy. This was another highly controversial play about a Black prize-fighter, loosely based on the career of Jack Johnson. There was some distaste towards a particular scene where Robeson dressed ‘only’ in boxing shorts became involved with a white woman.[9] Despite some negative opinions Robeson received excellent reviews. Throughout his career, he continued to play roles that defied Black stereotypes as he looked to project a positive and dignified view of African Americans.

In 1927 his career accelerated as he began to tour Europe in concert with Brown and practically became an overnight sensation with his rendition of ‘Ol’ Man River.’ He visited London in 1928 giving a concert at the famed Albert Hall. However, despite his success Robeson was still greeted with prejudice. In October 1929, he arrived in London but was refused entry into a London hotel.[10] In the late 1920s it was reported that this practice was becoming so prevalent that it had initiated a meeting by the Society of Friends to consider the matter. During the meeting, many other examples of Black men being refused entry into hotels were revealed, one of which was ‘Robert Abbott, a wealthy newspaper owner of Chicago, who found the doors of thirty London hotels closed to him.’[11] The meeting largely blamed the migration of South Africans and Americans who had expected Britons to ‘abandon our normal attitude of broadminded tolerance on their account.’[12] It was stated that hotels could not exercise colour prejudice on the grounds it may offend guests from other countries. However, Black men and women continued to be refused entry into hotels in London throughout the 1930s. Although, these events took place in the capital, the Hull Daily Mail reported on the matter in a column entitled ‘London Letter’ which enabled people in the East Riding to read about sensational or outrageous events.[13]

In May 1930, Robeson played the role of Moor in Shakespeare’s Othello at the Savoy Theatre. He was the first Black American to do so since Ira Aldridge. After the play ended, he travelled around Europe performing. Robeson returned to London in May 1931 to play the lead role in The Hairy Ape. Two months later he made his first visit to the East Riding of Yorkshire.

Throughout 1926 Robeson travelled across America singing for the hundreds of people who had gathered to hear his voice. In the Autumn, he accepted the lead role in the Black Boy. This was another highly controversial play about a Black prize-fighter, loosely based on the career of Jack Johnson. There was some distaste towards a particular scene where Robeson dressed ‘only’ in boxing shorts became involved with a white woman.[9] Despite some negative opinions Robeson received excellent reviews. Throughout his career, he continued to play roles that defied Black stereotypes as he looked to project a positive and dignified view of African Americans.

In 1927 his career accelerated as he began to tour Europe in concert with Brown and practically became an overnight sensation with his rendition of ‘Ol’ Man River.’ He visited London in 1928 giving a concert at the famed Albert Hall. However, despite his success Robeson was still greeted with prejudice. In October 1929, he arrived in London but was refused entry into a London hotel.[10] In the late 1920s it was reported that this practice was becoming so prevalent that it had initiated a meeting by the Society of Friends to consider the matter. During the meeting, many other examples of Black men being refused entry into hotels were revealed, one of which was ‘Robert Abbott, a wealthy newspaper owner of Chicago, who found the doors of thirty London hotels closed to him.’[11] The meeting largely blamed the migration of South Africans and Americans who had expected Britons to ‘abandon our normal attitude of broadminded tolerance on their account.’[12] It was stated that hotels could not exercise colour prejudice on the grounds it may offend guests from other countries. However, Black men and women continued to be refused entry into hotels in London throughout the 1930s. Although, these events took place in the capital, the Hull Daily Mail reported on the matter in a column entitled ‘London Letter’ which enabled people in the East Riding to read about sensational or outrageous events.[13]

In May 1930, Robeson played the role of Moor in Shakespeare’s Othello at the Savoy Theatre. He was the first Black American to do so since Ira Aldridge. After the play ended, he travelled around Europe performing. Robeson returned to London in May 1931 to play the lead role in The Hairy Ape. Two months later he made his first visit to the East Riding of Yorkshire.

"Nothing but the best for Bridlington"

|

After almost losing his voice while playing the part of ‘Yank’ in ‘The Hairy Ape’ in London, Robeson visited East Yorkshire to perform for locals. On 5 July 1931, Robeson sang negro spirituals and some European songs at the Royal Hall in Bridlington. In an interview for the Hull Daily Mail on 10 July 1931, the performer advised, “It is my first appearance before a Yorkshire audience, and I have always heard that they were very ‘difficult’. Yet they seem to be liking me.”[14] The crowd at the Spa Royal Hall loved Robeson and cheered for several encores to which the singer obliged.[15] Robeson was accompanied by his friend and gifted Black American composer, Brown who was the singer's right hand man for over thirty years.

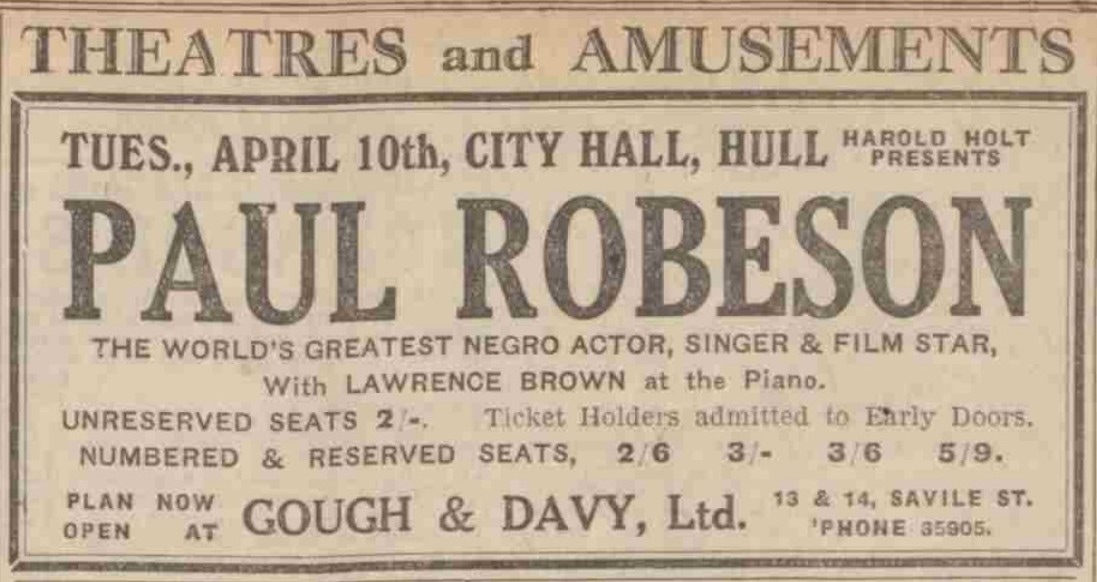

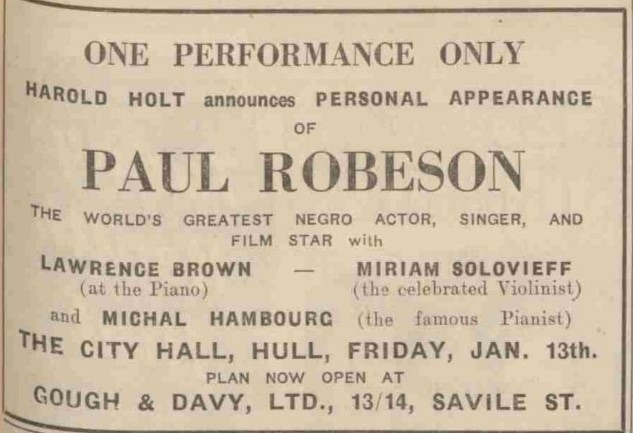

When Robeson had finished his tour, he travelled back to America. However, it was not long before the international star returned to Bridlington. On 29 August 1933, almost as soon as he arrived in England, Robeson appeared in Bridlington’s newly refurbished Royal Hall.[16] He performed “Poor ol’ Joe,” and “Ol’ Man River” among other songs for an audience of several thousand, some of whom had travelled great distances to see him.[17] Robeson in Hull In the spring of 1934, Robeson visited Hull to perform at the City Hall. He had removed the classical music from his repertoire and substituted it with folk songs from all over the world. In the early 1930s Robeson was critical of African Americans who did not acknowledge their roots and decided he would no longer include classical music in his concerts because it had no links to |

|

his heritage. Instead he decided to expand into global native music and began to study different languages in London. . It was reported that he was learning Swahili to aid his research into the folk music of Africa.[18] Over 2,000 people attended the City Hall concert and were in raptures over the entertainer’s presence.

After leaving Hull, Robeson continued his tour of Britain, when it was finished he left for Europe and met with members of the Soviet Union in Russia. He was reportedly particularly drawn to the Soviet Union because children were taught that racism was wrong. Robeson advised that the Russians accepted him as a human being and in no way thought of him as inferior.[19]

In 1935, Robeson became an international film star and was cast in several prominent roles. He appeared in both British and American movies throughout the 1930s and 1940s. However, his career was halted when he decided that the roles offered to him were demeaning to Black people. Robeson’s films were regularly shown at various cinemas in East Yorkshire during this era.

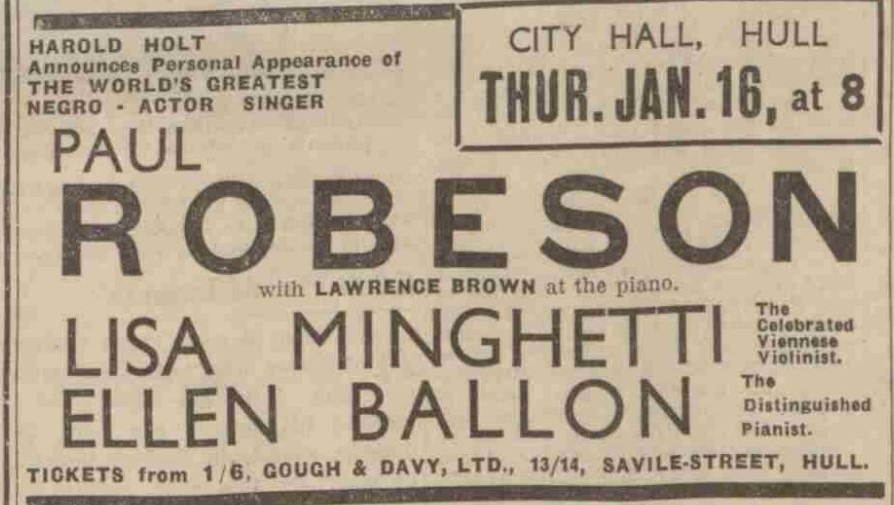

In January 1936, Robeson returned to Hull. Although his concert was scheduled for 16 January it was postponed for nine days after he was delayed in America.[20] Despite the short delay, people packed out the City Hall and a grateful Robeson advised the audience that, “I have just returned from my own America, but somehow I feel more at home here.”[21] During the concert, he sang classic negro spirituals and ballads from different parts of the world. He was also accompanied by Brown for his performance of “Joshua Fit de Battle of Jericho.” While he was in Hull Robeson stayed at the Station Hotel, where he was happy to be interviewed by a reporter of the Hull Daily Mail. They described Robeson as a charming and disarming individual.[22]

In 1935, Robeson became an international film star and was cast in several prominent roles. He appeared in both British and American movies throughout the 1930s and 1940s. However, his career was halted when he decided that the roles offered to him were demeaning to Black people. Robeson’s films were regularly shown at various cinemas in East Yorkshire during this era.

In January 1936, Robeson returned to Hull. Although his concert was scheduled for 16 January it was postponed for nine days after he was delayed in America.[20] Despite the short delay, people packed out the City Hall and a grateful Robeson advised the audience that, “I have just returned from my own America, but somehow I feel more at home here.”[21] During the concert, he sang classic negro spirituals and ballads from different parts of the world. He was also accompanied by Brown for his performance of “Joshua Fit de Battle of Jericho.” While he was in Hull Robeson stayed at the Station Hotel, where he was happy to be interviewed by a reporter of the Hull Daily Mail. They described Robeson as a charming and disarming individual.[22]

Two years later, on 16 December 1938, the Hull Daily Mail announced that Robeson was to make a brief visit to the region to perform ‘Songs of the Folk’ at the City Hall.[23] During this visit, Robeson told a newspaper reporter that some people believed that he had given up his role in politics. However, he advised “The people have got to be made to know how great they are… I want to speak to them and for them as a man still at the top of his own profession, a man who can claim a hearing. I want to show that people can take a stand as I have done and still keep up their professional careers.”[24] However, Robeson was soon to find out that people could not speak out and remain in high profile positions.

When he returned to the United States in the late 1940s, racist and political division were omnipresent. Despite obvious tensions Robeson continued with his quest to gain equality for Black people and to stop colonial powers exploiting Africa. However, his close links with the Soviet Union and propaganda regarding Robeson’s view that America was closely akin to a fascist state, which he denied, turned people against him. In 1949, a riot broke out at Robeson’s New York concert which prevented him from performing. The singer insisted that he wanted an inquiry into the riot which was reportedly caused by American ex-servicemen in response to his political views.[25] A week later, at a concert in Peekskill, New York another riot broke out.[26] These events led to yet another threat by the Ku Klux Klan in early September 1949, when an effigy was burnt with Robeson’s name on it in Birmingham, Alabama. The members stated that this was the welcome that Robeson would get should he ever visit the region.[27]

Robeson’s support for racial equality and what were deemed as dangerous political views eventually resulted in the American government revoking his passport for almost a decade under the McClarran Internal Security Act.[28] Although, the travel ban was lifted in 1958, he remained under surveillance by the FBI, CIA and MI5 for the rest of his life.

When he returned to the United States in the late 1940s, racist and political division were omnipresent. Despite obvious tensions Robeson continued with his quest to gain equality for Black people and to stop colonial powers exploiting Africa. However, his close links with the Soviet Union and propaganda regarding Robeson’s view that America was closely akin to a fascist state, which he denied, turned people against him. In 1949, a riot broke out at Robeson’s New York concert which prevented him from performing. The singer insisted that he wanted an inquiry into the riot which was reportedly caused by American ex-servicemen in response to his political views.[25] A week later, at a concert in Peekskill, New York another riot broke out.[26] These events led to yet another threat by the Ku Klux Klan in early September 1949, when an effigy was burnt with Robeson’s name on it in Birmingham, Alabama. The members stated that this was the welcome that Robeson would get should he ever visit the region.[27]

Robeson’s support for racial equality and what were deemed as dangerous political views eventually resulted in the American government revoking his passport for almost a decade under the McClarran Internal Security Act.[28] Although, the travel ban was lifted in 1958, he remained under surveillance by the FBI, CIA and MI5 for the rest of his life.

Almost as soon as he could travel, Robeson crossed the Atlantic and began a nationwide tour of Britain.[29] It was reported, that during this tour, he would perform a programme of popular ballads and folk songs at the Regal Cinema in Hull on 17 October 1958 [30].

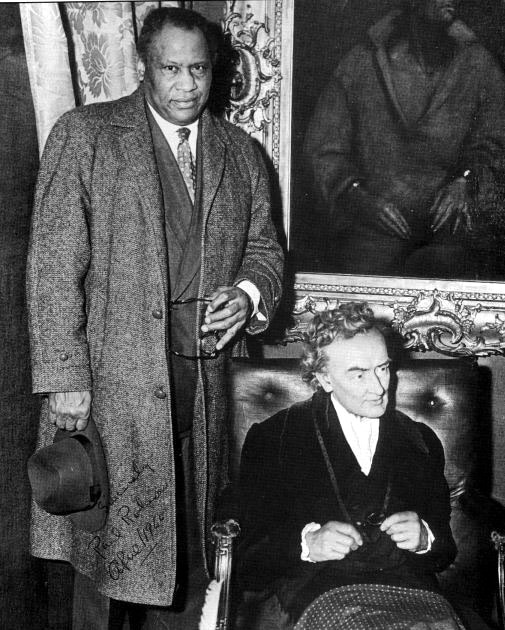

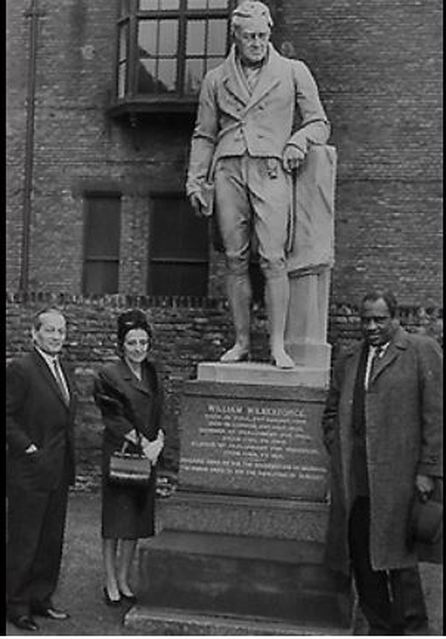

In 1959, Robeson played Othello for the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-Upon-Avon. After the play had finished he received an invitation to visit Hull to attend the celebrations for the bicentenary of Wilberforce’s birth which took place on 24 August. [31]. Although, his schedule meant that he could not attend, Robeson did travel to East Yorkshire in the latter months of 1959. The Haskins family recollects that after Hull businessman and Quaker, Alec Horsley, witnessed Robeson’s fantastic performance in Othello, he persuaded the actor to stay with his family during a private visit to the region.

In 1959, Robeson played Othello for the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-Upon-Avon. After the play had finished he received an invitation to visit Hull to attend the celebrations for the bicentenary of Wilberforce’s birth which took place on 24 August. [31]. Although, his schedule meant that he could not attend, Robeson did travel to East Yorkshire in the latter months of 1959. The Haskins family recollects that after Hull businessman and Quaker, Alec Horsley, witnessed Robeson’s fantastic performance in Othello, he persuaded the actor to stay with his family during a private visit to the region.

|

As promised on 24 April 1960, Robeson appeared at Hull City Hall. He sang to an ‘enthusiastic’ audience in French and German, told stories about his grandchildren and recited American poetry.[32]

During his stay, Robeson also visited Wilberforce House. The performer told the Hull Daily Mail, ‘My father often spoke to me about Wilberforce and I am very happy to be in the city of his birth.’ [34] After this, Robeson attended a reception at the Guildhall hosted by the Deputy Mayor and Sheriff of Hull. This was his last visit to the region before his death on 23 January 1976. |

Footnotes

[1] Philip S. Foner (eds.), Paul Robeson Speaks: Writings, Speeches, Interviews, 1918-1974, p. 27.

[2] Paul Robeson: Here I stand, documentary, 1999.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Philip S. Foner (eds.), Paul Robeson Speaks, p. 28.

[6] Paul Robeson: Here I stand, documentary, 1999

[7] Ibid.

[8] Hull Daily Mail, 30 October 1925, p. 2.

[9] Martin Duberman, Paul Robeson: A Biography, p. 53

[10] Hull Daily Mail, 23 October 1929, p. 4

[11] Ibid, p. 4.

[12] Ibid, p. 4

[13] Ibid, p. 4

[14] Hull Daily Mail, 10 July 1931, p. 10

[15] Ibid, p. 10

[16] Hull Daily Mail, 29 January 1932, p. 1

[17] Hull Daily Mail, 30 August 1933.

[18] Hull Daily Mail, 29 March 1934, p. 10

[19] Paul Robeson: Here I stand, documentary, 1999

[20] Hull Daily Mail, 3 January 1936, p. 5

[21] Hull Daily Mail, 27 January 1936, p. 10

[22] Hull Daily Mail, 27 January 1936, p. 4

[23] Hull Daily Mail, 16 December 1938, p. 15

[24] Hull Daily Mail, 14 January 1939, p. 4

[25] Hull Daily Mail, 31 August 1949, p. 5

[26] Hull Daily Mail, 5 September 1949, p. 5

[27] Hull Daily Mail, 8 September 1949, p. 3

[28] Hull Daily Mail, 4 August 1949, p. 5.

[29] The Stage, 11 September 1958.

[30] The Stage, 25 September 1958, p. 12.

[31] The Property and Bridges Committee minutes, 1959.

[32] Hull Daily Mail, 25 April 1960.

[33] The photograph was kindly provided by Lord and Lady (Chris and Gilda) Haskins. Standing is Susan Horsley (Gilda's mother) and sitting is Trudy Steiger,1959.

[34] L. 920 ROB

[1] Philip S. Foner (eds.), Paul Robeson Speaks: Writings, Speeches, Interviews, 1918-1974, p. 27.

[2] Paul Robeson: Here I stand, documentary, 1999.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Philip S. Foner (eds.), Paul Robeson Speaks, p. 28.

[6] Paul Robeson: Here I stand, documentary, 1999

[7] Ibid.

[8] Hull Daily Mail, 30 October 1925, p. 2.

[9] Martin Duberman, Paul Robeson: A Biography, p. 53

[10] Hull Daily Mail, 23 October 1929, p. 4

[11] Ibid, p. 4.

[12] Ibid, p. 4

[13] Ibid, p. 4

[14] Hull Daily Mail, 10 July 1931, p. 10

[15] Ibid, p. 10

[16] Hull Daily Mail, 29 January 1932, p. 1

[17] Hull Daily Mail, 30 August 1933.

[18] Hull Daily Mail, 29 March 1934, p. 10

[19] Paul Robeson: Here I stand, documentary, 1999

[20] Hull Daily Mail, 3 January 1936, p. 5

[21] Hull Daily Mail, 27 January 1936, p. 10

[22] Hull Daily Mail, 27 January 1936, p. 4

[23] Hull Daily Mail, 16 December 1938, p. 15

[24] Hull Daily Mail, 14 January 1939, p. 4

[25] Hull Daily Mail, 31 August 1949, p. 5

[26] Hull Daily Mail, 5 September 1949, p. 5

[27] Hull Daily Mail, 8 September 1949, p. 3

[28] Hull Daily Mail, 4 August 1949, p. 5.

[29] The Stage, 11 September 1958.

[30] The Stage, 25 September 1958, p. 12.

[31] The Property and Bridges Committee minutes, 1959.

[32] Hull Daily Mail, 25 April 1960.

[33] The photograph was kindly provided by Lord and Lady (Chris and Gilda) Haskins. Standing is Susan Horsley (Gilda's mother) and sitting is Trudy Steiger,1959.

[34] L. 920 ROB