British Black Presence from the Roman Period to the

Present Day and the new GCSE 'Migration in Britain' Module

By Martin Spafford

Part Three: Africans in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Britain

|

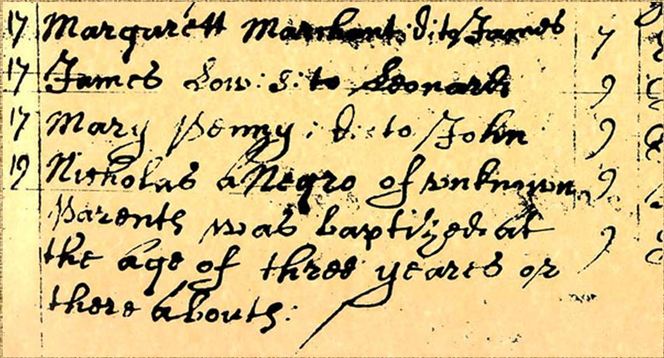

In the Early Modern era, the first Black child we know of living in London was Nicholas, baptised aged three at St Margaret’s, Westminster in 1619/20. How did he come to London? Why are his parents recorded as ‘unknown’? Where are they? In the eighteenth century such baptisms became more frequent, although not usually of such young children. |

|

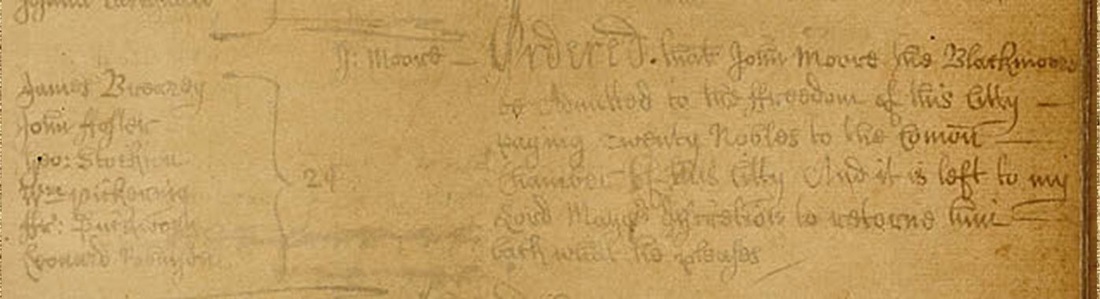

And the Freemen’s Roll of the city of York records in October 1687:

“Ordered. that John Moore the Blackmoore be Admitted to the Freedom of this Citty - paying twenty Nobles to the Common Chamber of this Citty And it is left to my Lord Mayors discretion to retorne him back what he pleases.”

“Ordered. that John Moore the Blackmoore be Admitted to the Freedom of this Citty - paying twenty Nobles to the Common Chamber of this Citty And it is left to my Lord Mayors discretion to retorne him back what he pleases.”

|

|

|

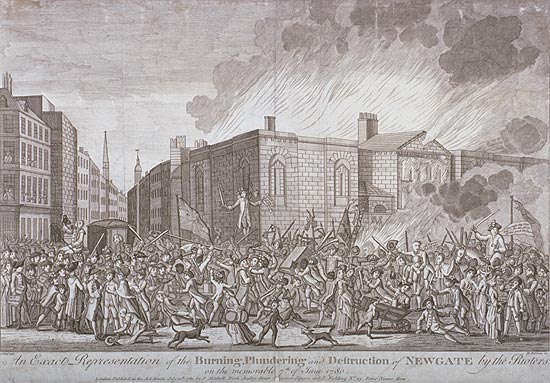

During the time of enslavement Black people appear as part of the general poor in William Hogarth’s satirical representations of London life, such as Noon (1738) to the right, and occasionally with much status, as in the 1733 painting in the National Gallery of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo ‘with the Qur’an round his neck’, by William Hoare. Diallo (below right), a former Senegambian prince who had been captured, enslaved on a Virginia plantation and then released, helped catalogue the Arabic books in the British Museum at its opening. Ignatius Sancho (1729-80), born on a slave ship, became a shop owner in Westminster and friend of the actor David Garrick. A classical music composer, he may have been the first African who - as a property owner - had the right to vote. He commented disparagingly on the Gordon Street rioters in 1780. One contemporary engraving (below) of the riots claims to be an ‘exact representation’ of the attack by the rioters on Newgate gaol. The building was set on fire and prisoners released - they can be seen in the crowd wearing leg irons. We know from the records that two Black men - Benjamin Bowsey and John Glover - were among the rioters outside the prison. Perhaps they are the two Black figures shown in the middle foreground of this picture. Glover and Bowsey were among those charged with ‘riotous and tumultuous assembly’. Convicted and sentenced to death in less than a month, they were held in Newgate prison (which had been attacked during the riots) awaiting execution. A surviving court document page shows that both were granted a stay of execution in July 1780. For some reason, Glover’s reprieve was indefinite - whereas Bowsey had to endure a series of temporary reprieves, until both men were conditionally pardoned in April the following year. Local records reveal that people referred to as 'Black' were employed in a variety of different jobs. While this was not common, opportunities did exist. There was a Black publican in Doncaster and a Black coal merchant in Kingston. Thomas Jenkins was an African farmhand who later spent a brief period studying at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. There, he met with objections to his presence, so he travelled to London where he trained and worked as a teacher at the British and Foreign School Society. A servant named Mingo was made keeper of the Harwich lighthouse in the will left by his master, Royal Navy surveyor Sir William Batten. At the centre of one of the largest narrative paintings in Tate Britain, The Death of Major Peirson, is a heroic Black figure. This is Pompey, Major Peirson’s servant, who is shown in the act of shooting the French sniper who had just killed his master. Click here for more information and to see the full painting. Though in reality Pompey would not have been wearing anything quite so grand, Copley depicted him dressed in the uniform of Lord Dunmore’s ‘Royal Ethiopian’ regiment, which was raised by Lord Dunmore from escaped slaves to fight against the Americans during the American Revolution. Many of the ‘Black Loyalists’ who fought for Britain in America eventually ended up among the poor on the streets of London and when ships took several in 1787 to settle in Sierra Leone, records show that the passengers included several Black women married to White men and White women married to Black men. |

By the mid-eighteenth century African and Asian people had become part of the fabric of British society. The history of White employers cannot be separated from the history of the men and women who worked for them. African, Caribbean and Asian people lived and laboured beside English washerwomen, domestic maids, cooks, sailors and soldiers. Among the many places where archivists have found 17th and 18th century mention of Black people in parish records are: Bexley, Bethnal Green, Beverley, Bedfordshire, Berkshire, Birmingham, Boston, Bristol, Canterbury, Carlisle, Carmarthenshire, Carshalton, Chelsea, Clwyd, Chelmsford, Cheltenham, Cornwall, Coventry, Chatham, Chester, Cumbria, Devon, Dorset, Enfield, Erith, Evesham, Faversham, Gloucestershire, Gravesend, Hastings, Hertfordshire, Isle of Sheppey, Lambeth, Lancashire, Leominster, Lewisham, Lincolnshire, Lymington, Manchester, Medway, Newport, Northampton, Pangbourne, Pembrokeshire, Plymouth, Oxfordshire, Rochester, Seaford, Stepney, Suffolk, Surrey, Tameside, Thetford, Westminster, Worcester and York. One example is St Mary’s Church, Leyton (now East London, then Essex) below. A decaying monument in the churchyard is dedicated to Sir Fisher Tench, local resident and owner of slave plantations in Barbados. The 1735 parish register records the death of “George Pompey a Black Servant to Sir Fisher Tench Sep 3” |