British Black Presence from the Roman Period to the

Present Day and the new GCSE 'Migration in Britain' Module

By Martin Spafford

Part Two: Africans in Medieval England

|

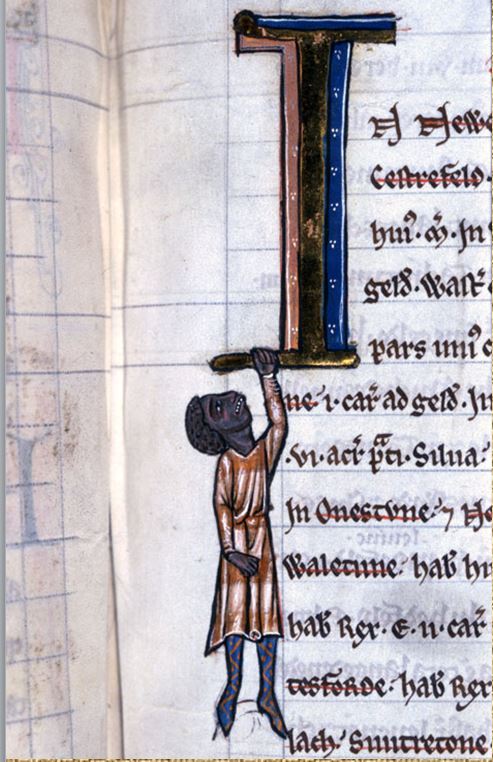

Moving to the Middle Ages, a 1241 Derbyshire version of the Domesday Book has the figure of a Black man hanging from an initial letter on one of its pages. Perhaps the artist had seen Black people, perhaps not. It is not necessarily positive or negative. However, the fact that a Black man is in a book listing people and land means that the artist was at least aware of the existence of African people. He is wearing a short tunic (a sign of low status) and striped clothing (often a sign of a troublemaker), so it may be a negative portrayal of someone disruptive. On the other hand, it may indicate that Black people were present doing useful work. Or perhaps the artist has just chosen an eyecatching image alongside all the others in the book of mythical animals and long-dead people from history. We cannot know.

|

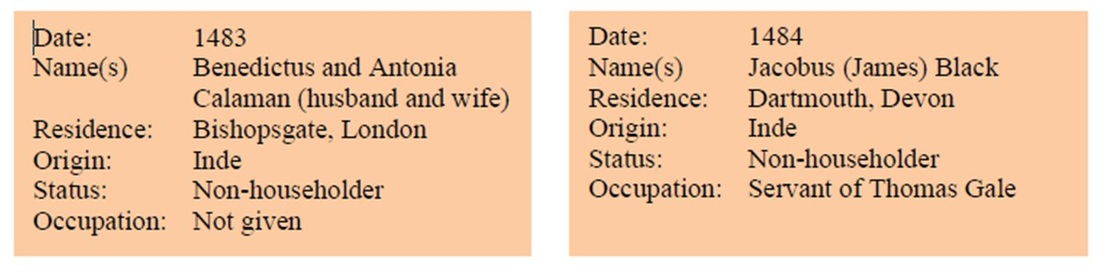

We do know, however, that a skeleton in Ipswich was identified in 2010 as being that of a medieval African man, and the ‘African immigrant from 300 AD’ found in Warwickshire and reported on in the Mail was in fact not from Roman times but, as we now know, from the 7th century. There was also an African woman in Fairford in the 10th or 11th century. In the register of those who paid the alien subsidies (taxes on foreign-born people) in the 1480s there appear servants from |

‘Inde’ called Jacobus Black (in Dartmouth, Devon) and Benedictus and Antonia Calaman (in Bishopsgate, London). Did ‘Inde’ mean India, or Africa, or somewhere else? Nevertheless, even if many people in late medieval England did not come across Africans, Asians, Muslims or Jews they certainly knew about them and their worlds. Books from all over England were full of stories about Saracens, Muslims, Chinese, Africans, Jews, Brahmins and Zoroastrians. Shops were full of spices from Arabia, Persia, India, Sri Lanka, China, Thailand, Moluccas and Indonesia, being sold at prices that ordinary people could afford. Crusader knights brought back many goods and ideas from the Muslim East.

Africans in Tudor England

|

The first settled African for whom we have a name and a face is John Blanke, court trumpeter to King Henry VIII, who appears alongside other trumpeters in the Westminster Rolls, painted to commemorate the celebrations at the birth of a son to Queen Katherine of Aragon. The son died in infancy. The document showing Blanke’s application, approved by the King’s signature, for a pay rise has survived, as has another showing the King’s gift at Blanke’s wedding. Other African residents of Tudor England included: Catalina, Moorish servant to Queen Katherine Anne Vause, married to a trumpeter called Anthonie Reasonabel Blackman, a silk weaver John Jaquoah, ‘a king’s son from Guinea in West Africa, sent by his father in an English ship to be baptised’ Mary Fillis, a basket maker whose father came from Morocco Symon, servant to a needle maker living near Mary |

|

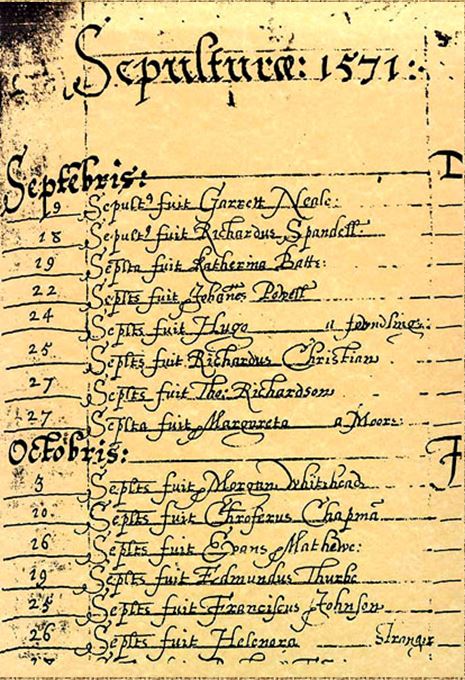

From a parish register we know of the burial of Margaret, a Moor, at St Martin-in-the-Fields in 1571. Very recent research into the Tudor period has revealed evidence of free Black people integrated in English society. In his book Blackamoores - Africans in Tudor England (2013), the historian Onyeka suggests that: “The evidence suggests that Africans in Tudor society were the most visible and numerous non-white people in sixteenth-century England... [They] may have been considered as less dangerous than white European Catholics ... the records that we have found so far suggest that most Africans were integrated into their local communities in a way that many white European immigrants were not.”

|

|

There is evidence to support this. In 1547 a West African called Jacques Francis was one of the divers salvaging from the wreck of the naval flagship Mary Rose, which had sunk in Portsmouth harbour. He gave evidence supporting his Italian employer who had been accused of theft. When other witnesses said Francis’s testimony should be banned because he had ‘slave’ status, the court supported Francis. Court records show that Black people in Tudor England had the right to a voice and equal respect under the law. A carving of St Maurice in Uffculme parish church, Devon, shows him as a Black man. William Shakespeare in Sonnet 132 (1609) wrote to his ‘dark lady’:

“Then will I swear beauty herself is black, And all they foul that thy complexion lack” On the other hand, the politician Sir Thomas More watched the arrival of Katherine of Aragon’s attendants and commented: “Good heavens - what a sight! If you had seen it I am afraid you would have burst with laughter, they were ludicrous... hunchbacked, undersized, barefoot pygmy Ethiopians. If you had seen them you would have thought they were refugees from hell.” We cannot be sure whether he was commenting on Black servants or darker skinned Spaniards, but his language shows that negative attitudes to Black skin existed. Meanwhile Sir John Hawkins and Sir Francis Drake were beginning their involvement in the trade in enslaved Africans. |

|

The historian Miranda Kaufmann has found over 400 documents recording the presence of Africans in Tudor and Stuart England: church baptism, burial and marriage records, tax returns, court records, letters, diaries and wills. She points out that the fact Black people were baptised - at a time when religion was so central to people’s lives - means they were accepted into the parish community. In Africans in Britain 1500-1640 (2011) she writes: |

|

“Once in Britain, they were to be found in every kind of household ... They performed a wide range of skilled roles and were paid in the same mix of wage, reward and gifts in kind as others. They were accepted into society, into which they were baptized, married and buried. They inter-married with the local population and had children... Africans in Britain were not viewed as slaves in the eyes of the law. Neither were they treated as such. They were paid wages, married, and allowed to testify in court.” |