David Oluwale (1930 – 1969)

By Dr Max Farrar

Secretary of the David Oluwale Memorial Association

Secretary of the David Oluwale Memorial Association

He arrived in Hull in 1949

He drowned in Leeds in 1969

Arrival in Hull

David Oluwale arrived on the Motor Vessel Temple Bar on 3 September 1949 at the port of Hull. He and two others had stowed away at Apapa Wharf in Lagos, Nigeria.

David, Victor Lapido Oyewole and Johnny Omaghomi had been smoked out of the hold of the MV Temple Bar within a couple of days of it leaving Lagos and they were put to work by the captain. They appeared in court as soon as the ship landed. Magistrate J H Tarbitten was unsympathetic. He wanted to know why they came to Hull — "Is there anyone on yonder side who suggests you come to this country?" he asked. "No," said Omaghomi. Oluwale’s reply, if he made one, is not recorded. They were sentenced to 28 days in jail for breaching maritime regulations (by not buying a ticket).

David was among the 1,600 stowaways estimated to have arrived in Britain between 1945 and 1951, two-thirds of whom came from West Africa and the rest from the West Indies. 83 other stowaways were found between 1948 and 1949 in Hull. [1]

David Oluwale arrived on the Motor Vessel Temple Bar on 3 September 1949 at the port of Hull. He and two others had stowed away at Apapa Wharf in Lagos, Nigeria.

David, Victor Lapido Oyewole and Johnny Omaghomi had been smoked out of the hold of the MV Temple Bar within a couple of days of it leaving Lagos and they were put to work by the captain. They appeared in court as soon as the ship landed. Magistrate J H Tarbitten was unsympathetic. He wanted to know why they came to Hull — "Is there anyone on yonder side who suggests you come to this country?" he asked. "No," said Omaghomi. Oluwale’s reply, if he made one, is not recorded. They were sentenced to 28 days in jail for breaching maritime regulations (by not buying a ticket).

David was among the 1,600 stowaways estimated to have arrived in Britain between 1945 and 1951, two-thirds of whom came from West Africa and the rest from the West Indies. 83 other stowaways were found between 1948 and 1949 in Hull. [1]

The Hull Daily Mail paid quite a bit of attention to these unwelcome visitors, reporting on their court cases and producing at least one feature article [click here to download article] and [click here for article transcription and commentary]. These articles start by warning the stowaways that there is no work in Hull for them (despite national unemployment at this time being 1.6%), but they do acknowledge the poverty and joblessness in West Africa. One magistrate commends those who fought for the British Forces in the war.

David Oluwale was transferred to Armley Jail in Leeds. He spent most of his next twenty years in the city.

Between 1949 and 1953, David’s friends described him as happy; he was “always making jokes and could be the life of the party”, according to Abby Sowe. David delighted in the nickname Yankee (acquired due to his admiration for American popular culture). He dressed sharply and enjoyed dancing at the Mecca Ballroom in Leeds. David’s friend and fellow Nigerian Gabriel Adams (Gayb), told me that when the West African men went out dancing, to overcome resistance from the white men, they had to make an arrangement with the DJ to have an ‘invitation’ moment, when the black men could cut in and ask a woman to dance. This went well for Gayb, who soon got married. One of his daughters, he told me, became a manager at Harvey Nichols in Leeds.

David had lots of jobs, doing the dirty work of reconstructing post-war Britain. He did manual work at Croft Engineering in Bradford. He was a hod carrier on a building site and he worked at the Public Abattoir and Wholesale Meat Market (next to Kirkgate Market) in Leeds. Then he did labouring work at Sheffield Gas Company. By autumn 1951 he was back in Leeds at the abattoir. Life was progressing as it did for most of the other Africans and African-Caribbeans in Leeds (there were only 985 of them in 1951): doing hard unskilled work, enjoying some entertainment and facing up to racism.

Between 1949 and 1953, David’s friends described him as happy; he was “always making jokes and could be the life of the party”, according to Abby Sowe. David delighted in the nickname Yankee (acquired due to his admiration for American popular culture). He dressed sharply and enjoyed dancing at the Mecca Ballroom in Leeds. David’s friend and fellow Nigerian Gabriel Adams (Gayb), told me that when the West African men went out dancing, to overcome resistance from the white men, they had to make an arrangement with the DJ to have an ‘invitation’ moment, when the black men could cut in and ask a woman to dance. This went well for Gayb, who soon got married. One of his daughters, he told me, became a manager at Harvey Nichols in Leeds.

David had lots of jobs, doing the dirty work of reconstructing post-war Britain. He did manual work at Croft Engineering in Bradford. He was a hod carrier on a building site and he worked at the Public Abattoir and Wholesale Meat Market (next to Kirkgate Market) in Leeds. Then he did labouring work at Sheffield Gas Company. By autumn 1951 he was back in Leeds at the abattoir. Life was progressing as it did for most of the other Africans and African-Caribbeans in Leeds (there were only 985 of them in 1951): doing hard unskilled work, enjoying some entertainment and facing up to racism.

Life, work and mental health

In April 1953 David was arrested after an altercation at the King Edward Hotel in the centre of Leeds. He was jailed for two months. In prison, it was said, he behaved strangely, and in June he was admitted to the psychiatric wing of St James Hospital. They referred him to Menston Asylum on the outskirts of Leeds. He was held there for the next eight years.

Violence was an ever-present threat for the West Africans in this period. Joe Okogba was warned by a Nigerian called Frank Morgan: “The white man — he want to fight you all the time”. Gayb told me that while most of the West Africans tried to avoid fighting David would always stand up for himself. Another Nigerian friend of David’s who worked with him in Hadfield Steel Works in Sheffield (in 1951) told Caryl Phillips that “He wouldn’t let anything go . . . If a foreman said something wrong to him it would be ‘fuck off’ . . . he was a stubborn, fighting man who simply found it impossible to back down and work the system”.[2]

Whether or not he was mentally ill in 1953, a diet of largactyl and electro shock therapy at Menston meant that, in 1961, when David was pitched back on the streets he was in very bad shape. His friends described him as “gone”, nervous, twitchy, slow, shuffling, and laughing for no reason. In 1962 he got another six months in jail for biting the finger of the park ranger on Leeds’ Woodhouse Moor. From 1963 he slept rough, or squatted, or briefly found a place at the Faith Lodge hostel for the homeless.

In 1965 he was back in custody for maliciously wounding two policemen. In Armley jail Dr Carty, called in from High Royds Hospital (the new name for Mention Asylum), described him as overactive, garrulous, aggressive, “very paranoid about the police” and hearing threatening voices, sometimes in Yoruba, sometimes in English. Carty concluded he was a “dullard”. David said he was a heavy drinker of sherry and rum. Of course, his encounters with the police might well have made him paranoid, but his symptoms are similar to those observed by his friends at this point, so he was, or had been made, mentally ill.

In April 1953 David was arrested after an altercation at the King Edward Hotel in the centre of Leeds. He was jailed for two months. In prison, it was said, he behaved strangely, and in June he was admitted to the psychiatric wing of St James Hospital. They referred him to Menston Asylum on the outskirts of Leeds. He was held there for the next eight years.

Violence was an ever-present threat for the West Africans in this period. Joe Okogba was warned by a Nigerian called Frank Morgan: “The white man — he want to fight you all the time”. Gayb told me that while most of the West Africans tried to avoid fighting David would always stand up for himself. Another Nigerian friend of David’s who worked with him in Hadfield Steel Works in Sheffield (in 1951) told Caryl Phillips that “He wouldn’t let anything go . . . If a foreman said something wrong to him it would be ‘fuck off’ . . . he was a stubborn, fighting man who simply found it impossible to back down and work the system”.[2]

Whether or not he was mentally ill in 1953, a diet of largactyl and electro shock therapy at Menston meant that, in 1961, when David was pitched back on the streets he was in very bad shape. His friends described him as “gone”, nervous, twitchy, slow, shuffling, and laughing for no reason. In 1962 he got another six months in jail for biting the finger of the park ranger on Leeds’ Woodhouse Moor. From 1963 he slept rough, or squatted, or briefly found a place at the Faith Lodge hostel for the homeless.

In 1965 he was back in custody for maliciously wounding two policemen. In Armley jail Dr Carty, called in from High Royds Hospital (the new name for Mention Asylum), described him as overactive, garrulous, aggressive, “very paranoid about the police” and hearing threatening voices, sometimes in Yoruba, sometimes in English. Carty concluded he was a “dullard”. David said he was a heavy drinker of sherry and rum. Of course, his encounters with the police might well have made him paranoid, but his symptoms are similar to those observed by his friends at this point, so he was, or had been made, mentally ill.

The Trial

The trial, in November 1971, of two police officers accused of the manslaughter and actual and grievous bodily harm of David Oluwale lasted for two weeks in Leeds Crown Court. Inspector Ellerker and Detective Sergeant Kitching denied all charges.

David Oluwale’s body had been found in the River Aire, a mile or so out of Leeds city centre, on 4 May 1969 by some boys playing near Knostrop Water Works. He was 5 feet 5 inches tall. Described in the trial as a ‘hurricane’, he weighed just ten stone. Since his final release from High Royds psychiatric hospital in 1967 he’d spent some time in prison in Leeds and Preston, and at the Church Army Hostel in The Calls in Leeds, but mostly he was sleeping rough. His West African friends who tried to help him when they ran into him said he was in a very bad way, not talking sense, laughing and looking over his shoulder all the time. The owner of a restaurant in the city centre said he looked “miserable and scruffy” but he was a “harmless type of person, [maybe] a bit mental”.[3]

When his body was found, Police Cadet Gary Galvin immediately shared his thoughts that Ellerker and Kitching were involved in David’s death. Galvin was based in Millgarth police station, where Ellerker and Kitching were his seniors. Galvin had heard the stories of their brutality towards David. Leeds police was notorious for its corruption and racism. Ellerker had already been sentenced to jail and dismissed from the force in 1969 after he tried to cover up the death of an elderly pedestrian caused by a police car driven by two of his drunken seniors. Black people feared the police. Leeds’ United Caribbean Association told a parliamentary enquiry in 1971 that:

Harassment, intimidation and wrongful arrest go on all the time ... police boot and fist [black] youths into compelling them to give

wrong statements ... We believe that policemen have every black person under suspicion... and for that reason every black

immigrant here in Leeds mistrusts the police.[4]

The trial, in November 1971, of two police officers accused of the manslaughter and actual and grievous bodily harm of David Oluwale lasted for two weeks in Leeds Crown Court. Inspector Ellerker and Detective Sergeant Kitching denied all charges.

David Oluwale’s body had been found in the River Aire, a mile or so out of Leeds city centre, on 4 May 1969 by some boys playing near Knostrop Water Works. He was 5 feet 5 inches tall. Described in the trial as a ‘hurricane’, he weighed just ten stone. Since his final release from High Royds psychiatric hospital in 1967 he’d spent some time in prison in Leeds and Preston, and at the Church Army Hostel in The Calls in Leeds, but mostly he was sleeping rough. His West African friends who tried to help him when they ran into him said he was in a very bad way, not talking sense, laughing and looking over his shoulder all the time. The owner of a restaurant in the city centre said he looked “miserable and scruffy” but he was a “harmless type of person, [maybe] a bit mental”.[3]

When his body was found, Police Cadet Gary Galvin immediately shared his thoughts that Ellerker and Kitching were involved in David’s death. Galvin was based in Millgarth police station, where Ellerker and Kitching were his seniors. Galvin had heard the stories of their brutality towards David. Leeds police was notorious for its corruption and racism. Ellerker had already been sentenced to jail and dismissed from the force in 1969 after he tried to cover up the death of an elderly pedestrian caused by a police car driven by two of his drunken seniors. Black people feared the police. Leeds’ United Caribbean Association told a parliamentary enquiry in 1971 that:

Harassment, intimidation and wrongful arrest go on all the time ... police boot and fist [black] youths into compelling them to give

wrong statements ... We believe that policemen have every black person under suspicion... and for that reason every black

immigrant here in Leeds mistrusts the police.[4]

The court heard from other officers that Ellerker and Kitching had taken David out of Leeds and dumped him, telling him never to return. But he always did. So they put him in a dustbin and rolled him down the street. They set fire to the newspapers he slept on. They urinated on him as he lay on the ground, grabbed his hair and banged his head on the ground.

Phil Ratcliffe, then working in the central charge office at Millgarth, told the court: “I have never seen a man crying so much and never utter a sound” as Kitching pushed his knee into David’s back at the charge counter. David, he said, was placid, far from violent, withdrawn and subdued. PC Hazel Ratcliffe testified that she had seen David kicked so hard in the groin while lying on the floor at Millgarth that he had been lifted off the ground. Even in those days, there were some police officers who had the courage, and the ethics, to speak out.

Ellerker got three years in jail and Kitching 27 months, convicted only of actual bodily harm. Judge Hinchcliffe had told the jury they could not consider the manslaughter charge. He thus ruled out the evidence of George Condon, a bus conductor. Condon told the jury he had seen a scruffily-dressed man being pursued down an alley off The Calls, close to the River Aire, by two men in police uniform at about 5am on 18th April 1969, the night that Oluwale disappeared.

The judge said this did not identify Oluwale, Ellerker or Kitching. Over a thousand police officers were able to prove to the enquiry, after inspecting their pocket books, that they were not in that part of Leeds at that time. Ellerker and Kitching were on duty that night, but, remarkably, they had lost their note-books for that night. Ellerker and Kitching came out of jail quite soon and got civilian jobs. They never answered any further questions.

Phil Ratcliffe, then working in the central charge office at Millgarth, told the court: “I have never seen a man crying so much and never utter a sound” as Kitching pushed his knee into David’s back at the charge counter. David, he said, was placid, far from violent, withdrawn and subdued. PC Hazel Ratcliffe testified that she had seen David kicked so hard in the groin while lying on the floor at Millgarth that he had been lifted off the ground. Even in those days, there were some police officers who had the courage, and the ethics, to speak out.

Ellerker got three years in jail and Kitching 27 months, convicted only of actual bodily harm. Judge Hinchcliffe had told the jury they could not consider the manslaughter charge. He thus ruled out the evidence of George Condon, a bus conductor. Condon told the jury he had seen a scruffily-dressed man being pursued down an alley off The Calls, close to the River Aire, by two men in police uniform at about 5am on 18th April 1969, the night that Oluwale disappeared.

The judge said this did not identify Oluwale, Ellerker or Kitching. Over a thousand police officers were able to prove to the enquiry, after inspecting their pocket books, that they were not in that part of Leeds at that time. Ellerker and Kitching were on duty that night, but, remarkably, they had lost their note-books for that night. Ellerker and Kitching came out of jail quite soon and got civilian jobs. They never answered any further questions.

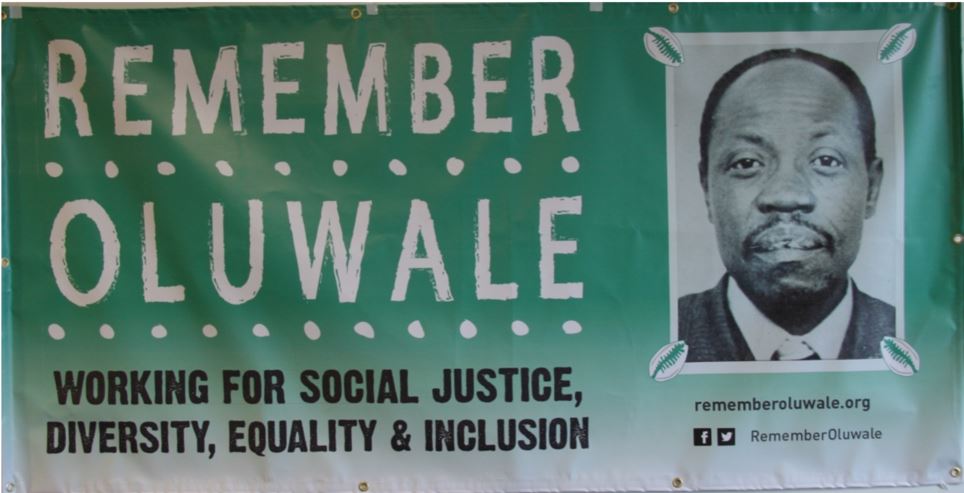

The David Oluwale Memorial Association

The Remember Oluwale charity [http://www.rememberoluwale.org/ ] aims to improve diversity, equality and social justice in the city of Leeds by both reminding the city of the grim history it has to come to terms with, and by educating and campaigning for change today in all the afflictions David endured. Their flagship project is the creation of a memorial garden close to the River Aire at the point where David was last seen, near the Leeds Bridge.

The Remember Oluwale charity [http://www.rememberoluwale.org/ ] aims to improve diversity, equality and social justice in the city of Leeds by both reminding the city of the grim history it has to come to terms with, and by educating and campaigning for change today in all the afflictions David endured. Their flagship project is the creation of a memorial garden close to the River Aire at the point where David was last seen, near the Leeds Bridge.

Footnotes

[1] See Tony Kushner, The Battle of Britishness - Migrant Journeys 1685 to the Present, (2012, Manchester: Manchester University Press).

[2] See the chapter on Oluwale titled ‘Northern Lights’ in Caryl Phillips (2007) Foreigners - Three English Lives, London: Harwill Secker.

[3] Unless otherwise attributed, all the direct quotes, and many of the facts in this article come from Kester Aspden (2008) The Hounding of David Oluwale, London: Vintage.

[4] House of Commons Select Committee on Race and Immigration 1971-2 Report on Police-Immigrant Relations, HC-1, HMSO, cited in Max Farrar (2002) The Struggle for Community Lampeter and New York: Edwin Mellen Press, p. 221. The latter is a very detailed sociological study of black-led social movements in Chapeltown, Leeds, UK, from the 1960s to the 1990s.

[1] See Tony Kushner, The Battle of Britishness - Migrant Journeys 1685 to the Present, (2012, Manchester: Manchester University Press).

[2] See the chapter on Oluwale titled ‘Northern Lights’ in Caryl Phillips (2007) Foreigners - Three English Lives, London: Harwill Secker.

[3] Unless otherwise attributed, all the direct quotes, and many of the facts in this article come from Kester Aspden (2008) The Hounding of David Oluwale, London: Vintage.

[4] House of Commons Select Committee on Race and Immigration 1971-2 Report on Police-Immigrant Relations, HC-1, HMSO, cited in Max Farrar (2002) The Struggle for Community Lampeter and New York: Edwin Mellen Press, p. 221. The latter is a very detailed sociological study of black-led social movements in Chapeltown, Leeds, UK, from the 1960s to the 1990s.