By John D. Ellis

On a warm summer day a dip in the waters of the Humber is a tempting way to cool down, however, the river is dangerous; with fast currents and nomadic sandbanks proving fatal to the unwary. In mid-August 1820 the soldiers of the 52nd (Oxfordshire) Foot had been stationed in Hull for two months. The regimental Head-quarters, (RHQ), and the band were quartered in the Citadel, (today the area known as Garrison), whilst the rest of the regiment was serving in detachments in Halifax and Scarborough. That the soldiers should be tempted to bathe in the Humber was not unusual, however, one bandsman got out of his depth and drowned.[1] That man can now be identified as Richard Lisles, an African-American soldier.

|

Lisles was born in Washington, USA, circa 1791. His origins are unknown, however, it is probable that he was one of the 3,000 slaves who joined the British during "the War of 1812" (1812-1815), and were then freed. In 1814 Washington was captured and the White House burned down by British soldiers, and it is likely that this was when Lisles took the opportunity offered to escape.[2]

Whilst the 52nd played no part in the War of 1812, other regiments stationed in Kent did, which might account for Lisles enlisting in Canterbury in October 1815.[3] On enlistment he was 24 years old, 5/6" tall and described as having black hair, black eyes and a black complexion.[4] His previous occupation was listed as labourer, and this lack of any apparent nautical experience might be why he chose the Army rather than the Navy. He was certainly not the only Black man from Washington to make that choice, as William Hart served in the 44th (East Essex) Foot from 1815 to 1839.[5]

One of Wellington's hard-fighting light infantry regiments, the 52nd were trained to use their initiative in battle, fighting in pairs in order to provide harassing fire against their enemies on the battle-field serving as either the advance or rear guard of the Army. In camp the regiment provided a piquet - patrolling in pairs. In a period when most soldiers fought in massed ranks, the pairing system required soldiers to use their initiative. (Whistles and bugle calls being used to communicate orders and warnings). From 1793 to 1815 the 52nd Foot had fought in the Iberian Peninsula, the Netherlands, France, North America and Waterloo. However, they were a fashionable regiment, and as such employed Black military musicians to promote regimental prestige as many other regiments did during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. When he enlisted Lisles was only the most recent in a line of individual Black soldiers to serve, (probably as big-drummer, cymbalist or tambourinest), in the 52nd since 1796.[6]

|

He served in Canterbury until May 1816 when he joined the 1st battalion 52nd Foot in France, where it had served since the Waterloo campaign. In the band he was under the command of Sergeant John Kilbanks, a German veteran of Waterloo.[7] The 52nd Foot remained on occupation duty until November 1818 when they returned to England, with the regimental band being prominent on arrival at Ramsgate.[8] Under their Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Rowan (1782-1852), the 52nd returned to a country in turmoil. The end of the Napoleonic Wars saw famine, chronic unemployment and political agitation for parliamentary representation. They found themselves immediately thrown into aiding civil powers in the Midlands. In February 1819 they were policing colliery disturbances in St Helens, and the following month acting as fire-fighters in Chester, duties for which the Chester Courant reported that they deserved the "highest praise".[9]

Charles Rowan had made a name for himself in the Peninsula and Waterloo campaigns, and his period in command of the 52nd in its "aid to civil powers" role, revealed him to have be as able and astute a diplomat as he was a soldier. Under Rowan the 52nd mounted a charm offensive where-ever they were stationed. In Chester, in March 1819, they gave "a magnificent ball and supper" to which "the beauty of and fashion of Chester city and county" were invited.[10] The band also participated in "keeping the army in the public eye," with the Staffordshire Advertiser describing them as "excellent" at a concert they supported in Lichfield in November 1819.[11] However, it was not all balls, bands and dancing. August 1819 saw the "Peterloo Massacre" and sixteen civilian deaths at the hands of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry. Whilst the latter, unlike the men of the 52nd, were neither regular nor experienced soldiers, the incident inflamed tensions between soldiers, oft stereotyped as "brutal", and civilians.

In December 1819, elements of the regiment were stationed in Nottingham guarding a large quantity of ammunition against potential radical attack.[12] In January 1820, in Lichfield, the night guard was doubled and every third man slept with his weapon in anticipation of an attack by "a Corps of Radicals coming from Birmingham."[13]

Under Rowan's command the 52nd Foot were judged to have had a successful policing "tour", and this was to stand him in good stead when he eventually left the regiment. In June 1820 the 52nd were ordered north, arriving in York later that month, with elements en-route for Hull (where the Head Quarters, including the band, were to be stationed), Halifax and Scarborough.[14] The Citadel at Hull had long been depot to a number of infantry regiments, whilst deployments to Halifax and Scarborough were more traditional – the former being similar work to that recently undertaken in the Midlands, and the latter being anti-smuggling duties.

At half past seven on the morning of Friday 11th August 1820 Lisles was one of a group of soldiers who left the Citadel on the north bank to bathe in the Humber. Newly arrived, it is unlikely that the soldiers were aware that in the years preceding their arrival the Hull Packet had reported on several cases of drownings: From fishermen whose boats had capsized, to experienced sailors who had lost their footing on the docks, fallen in and been swept away by the currents.[15]

The Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser recounted what happened next:

As the Black belonging to the band of the 52nd regiment was bathing in the Humber, he got out of his depth, and was drowned, in the presence of about dozen of his comrades; some of whom, it is said, were good swimmers, and yet did not attempt to render him assistance.[16]

- Head to the Vision of Britain website for a contemporary print showing the Citadel and its environs. Lisles drowned on the north bank of the Humber, and was buried in nearby Drypool the following day.

It is not known what exactly what happened, but clearly the journalist concerned saw the inaction of the soldiers who "did not to render assistance" as being out of the ordinary. It might be that they were frozen with shock, fearful of trying to risk their lives in a rescue attempt – an unlikely scenario considering the initiative required to be a light-infantryman and the previous combat and policing experience of the men concerned, especially Sergeant Kilbanks. It could have been because either Lisles was personally unpopular (and therefore deemed undeserving of help), or because he was Black.[17]

Perhaps, it was simply that the men of the 52nd, hardened to death by years of campaigning and brutalised by policing duties had quickly and accurately calculated the risks involved in any rescue and deemed them too great.

Paradoxically whilst Lisles met his fate watched by his erstwhile comrades, in 1826 the Taunton Courier, and Western Advertiser reported the heroic efforts made by a Black man of the 32nd (Cornwall) Foot who dived into French Weir, Taunton, in order to rescue a man swept away whilst bathing.[18] Even though it became clear that the man must have drowned, the Black soldier "courageously and skilfully dived into various parts of the stream, and at length brought up the corpse."[19] The newspaper reported that he was rewarded with £3 by benevolent onlookers, but failed to mention his name.[20]

The body of Richard Lisles was buried on Saturday 12th August 1820 in the cemetery of St Peter's Church, Drypool, with the service being conducted by Reverend Richard Moxon, the Curate of Drypool and Sutton.[21]

Postscript: People

John Kilbanks, Band-Sergeant of the 52nd Foot, was discharged on a pension in Dublin in 1821, and died in Brighton in 1849.[22]

John Kilbanks, Band-Sergeant of the 52nd Foot, was discharged on a pension in Dublin in 1821, and died in Brighton in 1849.[22]

Charles Rowan took the 52nd to Ireland in 1821, and resigned his commission the following year. In 1829 he was approached by Sir Robert Peel and invited to become one of the two founding Commissioners of the new Metropolitan Police. Rowan provided the military discipline and organisation, (the "beat system", military "drill" and high standards of personal conduct were apparently modelled on the 52nd Foot), and barrister Richard Mayne the legal expertise. Rowan was made a Knight Commander of the Bath, (KCB), in 1850 and died in London 1852.

Reverend Richard Moxon became Curate of Ilkeston in Derbyshire. He died there in 1836 aged 44 years, with his obituary noting that he was brother to Mr B. Moxon, druggist of Hull.[23] Years later Moxon was still remembered fondly by one Ilkeston parishioner:

"Is there a single individual in Ilkeston who can say aught disrespectful of that excellent man? I, and very many others, have much to be thankful for to him. The pains he took to assemble us on the Sunday afternoon, to explain to us the scriptures; the benevolent smile he gave as we vied with each other in answering the questions he put, were more than enough to repay us: and he, I have no doubt, has his reward."[24]

Postscript: Places

The Citadel, Hull. Military use of the Citadel stopped in 1848. In the 1860s it was sold and the land cleared. All that remains today is a single watch-tower at the area of Victoria Dock.

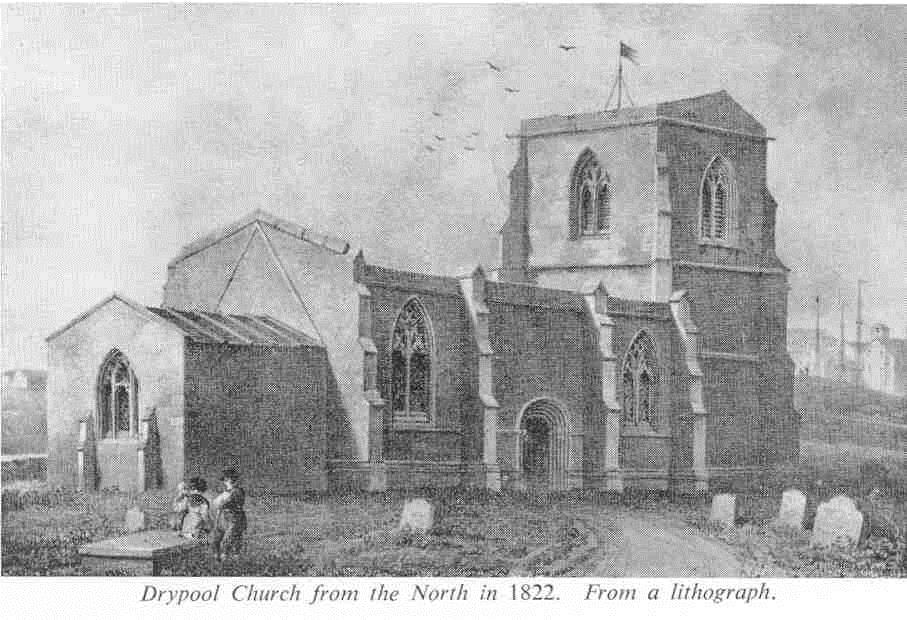

A lithograph showing Drypool Church c.1822. By 1822 St Peter's Church was in such a state of disrepair that it was demolished. Reverend Moxon preached the last sermon on the text: "But the end of all things is at hand." (Peter: VII). The churchyard was closed to further burials in 1855.[25]

Postscript: The 52nd

The 52nd (Oxfordshire) Regiment of Foot went on to serve in the Indian Mutiny (1857-1858). With them was Lieutenant Reginald Wilberforce, the son of William Wilberforce of Hull. In his memoirs Reginald Wilberforce referred to his service in the regiment as "…a distinction that I cherish to this day…"[26] They are one of the antecedent regiments of "The Rifles", a regiment that recruits heavily in Yorkshire.

The 52nd (Oxfordshire) Regiment of Foot went on to serve in the Indian Mutiny (1857-1858). With them was Lieutenant Reginald Wilberforce, the son of William Wilberforce of Hull. In his memoirs Reginald Wilberforce referred to his service in the regiment as "…a distinction that I cherish to this day…"[26] They are one of the antecedent regiments of "The Rifles", a regiment that recruits heavily in Yorkshire.

John Lewis Friday

Read about John Lewis Friday, another infantry soldier from the early 19th Century.

Footnotes

The initial research that provided the basis for this study was undertaken for my MA thesis, and a synopsis can be provided on request. JD. Ellis, "The visual representation, role and origin of Black soldiers in British Army regiments during the early nineteenth century." (Unpublished MA thesis, University of Nottingham, 2000).

The initial research that provided the basis for this study was undertaken for my MA thesis, and a synopsis can be provided on request. JD. Ellis, "The visual representation, role and origin of Black soldiers in British Army regiments during the early nineteenth century." (Unpublished MA thesis, University of Nottingham, 2000).

- Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 15 August 1820.

- Edward Baptist, born in Martinique c.1779, served as a musician in the band of the 44th (East Essex) Foot from 1798 to 1821, including service in the "War of 1812" when the 1st Battalion burned down the White House. He was discharged on a pension in Dublin. See TNA WO 12/5649, WO 119/43 and 64.

- TNA WO 12/6253 and WO 25/407 and 410. There is nothing in the records that suggests Richard Lisles was purchased as a slave, and his enlistment and subsequent service matches that of the White soldiers who enlisted at the same time.

- TNA WO 12/6253 and WO 25/407 and 410.

- A married man, Hart settled in India and died in 1840. For Hart see TNA WO 12/5649, WO 23/11 and 149. TNA WO 97/593/77. BIO Ecclesiastical Returns: Marriages. N-1-33/159. British India Office Deaths & Burials. Parish register transcripts from the Presidency of Bengal:1713-1948. Fort William, Bengal. N-1-58. Page: 4.

- Thomas Hargar, "an East Indian" served from 1796 to 1798, then transferred to the 77th (East Middlesex) Foot where he served until 1819. See TNA WO 25/333, WO 25/473 and WO 119. John Fitzhenry of Jamaica served from 1798 to 1802. He had then been discharged, later serving in the 14th Dragoons from 1804 to 1825. See TNA WO 97/47. John Williams of Malta served from 1809 until 1813 when he deserted in Shorncliffe, Kent. See TNA WO 25/409.

- Kilbanks was born c.1774. He had served with the 10th Dragoons (1796-1801), 4th Foot (1801-1805) 7th Dragoons (1805-1810) and 52nd Foot (1814-1821). All regiments which employed Black soldiers. See: TNA WO25/407, WO 119 and WO 120/60.

- Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 28 November 1818. Also Moorsom, WS (Ed.), Historical Record of the Fifty-Second Regiment (Oxfordshire Light Infantry) from the year 1755 to 1858. Second edition. (Richard Bentley, New Burlington Street, London, 1860). pp. 273-278.

- Stamford Mercury, 19 February 1819. Chester Courant, 09 March 1819.

- Morning Post, 26 March 1819.

- Staffordshire Advertiser, 20 November 1819.

- Salisbury and Winchester Journal, 27 December 1819.

- Manchester Mercury, 4 January 1820.

- Yorkshire Gazette, 10 June 1820.

- Editions of the Hull Packet for the following dates reference either individual or multiple drownings in the Humber: 03 April 1810, 23 June 1812, 22 July 1817, 14 February 1815, 17 March 1818 and 28 July 1818.

- Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 15 August 1820.

- It is not the intent of this writer to retrospectively label the 52nd as racist, they were after all providing employment and a level of equality to Black soldiers during the period of slavery. The Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, also did not accuse it of racism. However, the regiment failed to retain Black soldiers. Out of the four known to have served, one transferred to another regiment, one left (only to re-enlist in another regiment), one deserted and Richard Lisles died with no attempt being made to save him. See reference #6. Also Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser 15 August 1820.

- Taunton Courier, and Western Advertiser, 19 July 1826.

- Taunton Courier, and Western Advertiser, 19 July 1826.

- The victim was Edward Squibb Cornish, aged 22. Two Black soldiers, John Charles and Francis Augustine, were serving in the band of the 32nd at the time. The former was discharged in 1829 and therefore probably not physically capable of the rescue, whilst the latter was in his early 30s, 6/1 and ¼" tall and the more likely hero. At the time of the incident the 32nd Foot were passing through Taunton en-route for quarters in the North of England, (including Bradford, Halifax and Wakefield). John Charles was still serving in the band of the 32nd when it returned to Yorkshire in 1843, and played at Leeds Zoological and Botanical Gardens.

Francis Augustine, a servant born in St Domingo c.1782, served from 1806 to 1829. See WO 97/504/27. John Charles, a servant born in Trinidad c.1793, served from 1808 to 1845. Charles was the big-drummer of the 32nd and he and his Irish born wife, Ann, settled on the Isle of Man. He died in 1862 and she in 1874. See TNA WO 25/366 and 368, WO 97/505 and WO 120/57-61. Historical Records of the 32nd (Cornwall) Light Infantry: Now the 1st Battalion Duke of Cornwall's L.I., from the Formation of the Regiment in 1702 Down to 1892. Colonel GC. Swiney, (Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., Limited, 1893). Leeds Times 10 June 1843. - See East Riding Archives and Local Studies Service, Yorkshire Burials. PE 109/67. Page 97.

- See: TNA WO25/407, WO 119 and WO 120/60.

- The Gentleman's Magazine, (London, England), Volume 159, 1836.

- www.oldilkeston.co.uk/the-highway-board

- drypoolparish.org.uk/drypoolparish/HistoryBook/index

- Wilberforce, RG. "With them goes Light Bobbee: A first-hand account of the Indian Mutiny of 1857, by a Junior Officer of the 52nd Light Infantry," (Lenuer Ltd, 2011).