By Lauren Eglen

Una Maud Victoria Marson was born on 6 May 1905 in Sharon Village, St Elizabeth, Jamaica to Reverend Solomon Isaac and Ada Marson. She was the youngest of six children, along with three other children her parents adopted, but lived a relatively prosperous life in comparison to other Jamaicans.[1] From a young age Marson was introduced to poetry by her sisters Edith and Ethel – something that she later referred to as ‘the chief delight of our childhood days’.[2]

|

In 1915 Marson entered Hampton High boarding school, a prestigious school in which Jamaican girls could receive an English public school education. Students were mainly from wealthy white and creole families, thus Marson (Black and middle class) was well versed in the operations of racism by the time she left.[3]

Marson left Hampton in 1922, moving to Kingston in search of opportunity and prosperity. The first step in this direction came in January 1926 when Marson, almost twenty one, began working as assistant editor on the socio-political journal the Jamaica Critic. However, Marson found her work at the Critic restricted to ‘feminine subjects’ by its anti-feminist owner T. Dunbar Wint, thus preventing her from the social commentary that was to become her hallmark.[4] Marson felt the responsibility to draw attention to both the problems and possibilities facing Black women, and it was this that led her to leave the Critic and in 1928 become Jamaica’s first female editor-publisher with her own monthly The Cosmopolitan. The Cosmopolitan was created to ‘do all we can to encourage talented young people to express themselves freely’ and to develop ‘literary and other artistic talents in our Island’.[5] Marson was especially concerned with developing the literary talent and highlighting the concerns of women, proclaiming in the pages of her first edition ‘This is the age of woman: What man has done women may do’.[6] The Cosmopolitan ran from May 1928 to 1931, featuring poetry, short stories and articles. While the publication struggled to find an audience, The Cosmopolitan offered an important opportunity for West Indian writers, even if they could often look only to national newspapers for occasional publication. |

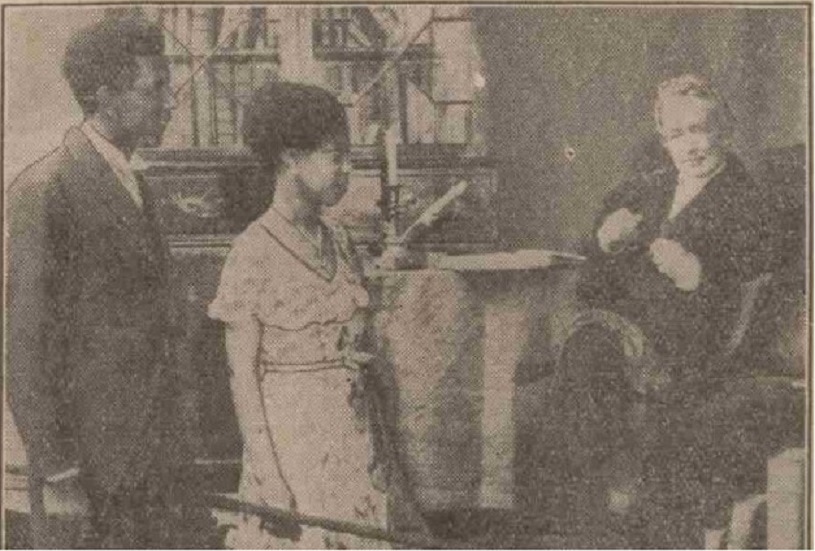

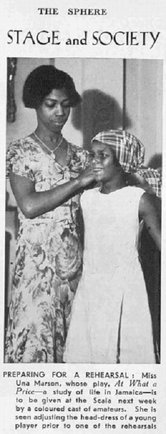

As well as her journalistic career, Marson was adept in a number of literary genres. She published a number of poetry collections in which she explored the relationships between men and women in a male-dominated society and further highlighted her feminist consciousness. Her first collection, Tropic Reveries, was released in 1930 (read it here), however, it was her second collection Heights and Depths (1931) (read it here), that reveals how conscious she had become of her social environment and in her writing further asserts her interest in women’s experiences. Marson also wrote her first play At What a Price during this time. Telling the story of a Jamaican girl who moves to Kingston to work as a stenographer and falls in love with her white male boss, it was staged at Kingston’s Ward Theatre on 11 June 1932 and praised for its focus on Jamaican themes, characters and settings.[7]

That same year, Marson sought out a broader and more challenging audience, moving to London in July. She stayed in Peckham at the house of Jamaican-born Dr Harold Moody, who had founded the League of Coloured Peoples (LCP) in 1931. Marson initially struggled to adjust to life in London. Her first impressions can be gauged from her poem ‘Nigger’. Published in the LCP’s official organ The Keys. it remained Marson’s most indicting critique of British racism (read it here). In the poem Marson traces her painful reaction to being called ‘Nigger’ and traces it back to its roots in slavery when it was used as a term to dehumanize Blacks, justifying their enslavement, and its continued use to reinforce their inferiority in the eyes of whites.

|

The League’s commitment to addressing issues of racial division and prejudice was a comfort to Marson at this time. In 1933, after a year of trying to find work, she became the unpaid secretary of the LCP, organising receptions, meetings, trips and maintaining contact with Afro visitors to Britain.

In July 1933, Marson accompanied Harold Moody to the Wilberforce Centenary Celebrations in Hull at the invitation of the Lord Mayor, along with other League members Stella Thomas, Evelyn Hartree and Basil Rogers. Throughout the week of 23-29 July, the city of Hull saw a number of events and exhibitions seeking to commemorate the centenary of the death of William Wilberforce and the abolition of slavery within the British Empire |

An exhibition at City Hall Mortimer Galleries was opened by Lady Illingworth on Tuesday 25 July. Intended for a large assembly it housed paintings depicting ‘negro and slave life’ covering the walls. However, the exhibition considered ‘the most spectacular effect’ was the figure of Wilberforce created by Madame Tussauds, London, which Marson can be seen inspecting in the newspaper image above. Further exhibits included paintings, prints, pottery, medals and the model of a slave dhow, along with some of the cruel instruments of slavery, which Wilberforce used in the House of Commons to clinch his arguments.[8]

|

At the opening of this exhibition, after the Lord Mayor rose to thank Madame Tussauds for their gift, a recital of negro spirituals followed with native sketches by Rodgers, Marson, and Thomas was performed.[9] Marson took part in a mock Victorian exhibition of freaks and objects, including slave relics such as whips and iron collars. Placing herself alongside the tableau of Wilberforce, she was filmed acting out a lifelike reproduction of a West Indian market seller in the Mortimer Galleries, in the hope of providing a spectacle that would increase racial understanding.[9]

In November 1933, Marson put on a League performance of her play At What a Price, as proof that the League was going places.[11] On 15 January it began a three-night run at the Scala Theatre as the first Black colonial production in the West End (see right).[12] In 1934 Marson became editor of The Keys. While in London, she became affiliated with a number of women’s organisations including the Women’s Freedom League, Women’s International Alliance and the British Commonwealth League. In 1935, she was the first Jamaican invited to speak at the International Alliance of Women for Suffrage and Equal Citizenship in Istanbul, as a representative of the Women’s Social Service club in Jamaica. That same year, she became the first Black woman invited to attend the League of Nations in Geneva by Abyssinian Emperor Haile Selassie.[13] |

Marson’s political consciousness had been deeply affected by her time in London - particularly by her time spent with African King Sir Nana Ofori Atta Omanhene, whose influence had brought her to the realisation that Africa mattered. Thus, on her return to Jamaica in September 1936, the notion of a transnational Black alliance had become integral to her intellectual convictions.[14] Marson’s time with Atta, discussing African politics, also inspired her 1937 play London Calling about Caribbean students in London and their attitude to the stereotypes with which the British viewed Africans and Afro-Caribbeans.[15]

Back in Jamaica, Marson resumed her work as a journalist, writing a column for the weekly Public Opinion. in August 1937, she also set up the first interracial club in Jamaica, the Readers & Writers Club. In September 1937, Marson’s third collection of poems, The Moth and the Star, was published (read it here). This collection was overtly racial as her poems put forward a positive self-image for Black women and rejected the devaluing force of whiteness. This is evidenced in her poem ‘Kinky Hair Blues’: “I like me Black face/And me kinky hair/But nobody loved dem/I jes don’t think it’s fair”.[16] Marson’s critique of the white ideal continued in her next and most successful play Pocomania, which opened in January 1938. Pocomania looks at the struggle of a Black middle-class woman attempting to reclaim her African heritage and free herself from a repressive colonial society and was one of the first plays to present the creole language on stage.[17]

Marson continued her social work, setting up the Jamaica Save the Children Association (JAMSAVE), but after returning to London to raise funds, she chose to stay in Britain.[18] In 1939, she received an invitation to BBC headquarters from Cecil Madden, the producer of the popular magazine programme Picture Page. Marson did freelance work for this programme and the BBC more generally throughout the early years of WWII. On 3 March 1941, her trial period was over and Marson was appointed full time programme assistant on the Empire Service, compering and co-ordinating broadcasts under the title Calling the West Indies.[19] In 1942, Marson was promoted to West Indies producer and made it her mission to find West Indians everywhere for her four-night-a-week talks.[20] She appeared in John Page’s propaganda film Hello! West Indies (1943) (view it here) in which she played a hostess, presenting speakers who told stories of their wartime experiences.

Back in Jamaica, Marson resumed her work as a journalist, writing a column for the weekly Public Opinion. in August 1937, she also set up the first interracial club in Jamaica, the Readers & Writers Club. In September 1937, Marson’s third collection of poems, The Moth and the Star, was published (read it here). This collection was overtly racial as her poems put forward a positive self-image for Black women and rejected the devaluing force of whiteness. This is evidenced in her poem ‘Kinky Hair Blues’: “I like me Black face/And me kinky hair/But nobody loved dem/I jes don’t think it’s fair”.[16] Marson’s critique of the white ideal continued in her next and most successful play Pocomania, which opened in January 1938. Pocomania looks at the struggle of a Black middle-class woman attempting to reclaim her African heritage and free herself from a repressive colonial society and was one of the first plays to present the creole language on stage.[17]

Marson continued her social work, setting up the Jamaica Save the Children Association (JAMSAVE), but after returning to London to raise funds, she chose to stay in Britain.[18] In 1939, she received an invitation to BBC headquarters from Cecil Madden, the producer of the popular magazine programme Picture Page. Marson did freelance work for this programme and the BBC more generally throughout the early years of WWII. On 3 March 1941, her trial period was over and Marson was appointed full time programme assistant on the Empire Service, compering and co-ordinating broadcasts under the title Calling the West Indies.[19] In 1942, Marson was promoted to West Indies producer and made it her mission to find West Indians everywhere for her four-night-a-week talks.[20] She appeared in John Page’s propaganda film Hello! West Indies (1943) (view it here) in which she played a hostess, presenting speakers who told stories of their wartime experiences.

|

Perhaps the most important and influential of Marson’s creative inventions for the BBC was Caribbean Voices, the literary segment of Calling the West Indies. First airing on 11 March 1943, it enabled her to establish an avenue through which peoples and cultures could speak to each other, putting forward the ideal of collaborative effort and mutual education. Historian Edmund Braithwaite has called the programme ‘the single most important literary catalyst for Caribbean creative and critical writing in English’.[21] However, while the BBC utilised her voice to foster imperial unity, Marson herself faced great prejudice from fellow colleagues who were often uncomfortable with her colour. Marson had always suffered bouts of depression, but in 1945, after having lived without family or close friends, working long hours, the depression resurfaced.[22]

Marson arrived back in Jamaica in April 1946, and was out of the public eye for almost two years due to her illness. Though she would continue her social and journalistic work and continue to engage in political activism in the Caribbean, America and Israel for the next twenty years, Marson never regained the momentum of her earlier work. Whilst speaking at a three-day conference in Jerusalem in 1965 on The Role of Women in the Struggle for Peace and Development, Marson was taken extremely ill and was flown back to Jamaica on 10 April.[23] After 10 days in hospital, Marson suffered a heart attack and died on 6 May 1965. |

|

While Una Marson has often been neglected by history, through her life and work she demonstrated the early stirrings of a Black feminist-nationalist agenda, recognising the use of literary culture in activism. Marson brought Caribbean culture to London through her work in radio, her poetry and her political activism and utilised such literary culture to comment on the social issues of race and gender experienced across the Empire. |

Footnotes

[1] Delia Jarrett-Macauley, The Life of Una Marson,1905-1965 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998). p.5

[2] Talking it Over broadcast 11th July 1940 in Jarrett-Macauley, The Life of Una Marson 1905-1965

[3]Alison Donnell, ‘Una Marson: Feminism, Anti-Colonialism and a Forgotten Fight for Freedom’, in West Indian Intellectuals in Britain, ed, by Bill Schwartz (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003), p.114.

[4] Jarrett-Macauley, p.30.

[5] Donnell, p.116.

[6] Una Marson, ‘Editorial’, The Cosmopolitan: a monthly magazine for the business youth of Jamaica and the official organ of the Stenographer’s Association, Vol. 1 No.1 (May 1928), p.5. in Imaobong D. Umoren, ‘This is the Age of Woman’: Black Feminism and Black Internationalism in the Works of Una Marson, 1928-1938)’ History of Women in the Americas, 1:1 (April 2013), pp.50-73.

[7] Jarrett-Macauley, p.43.

[8] Ibid.

[9] The Daily Mail, Tuesday July 25th 1933.

[10] Jarett-Macauley, p.53.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Umoren, p.51.

[14] Donnell, p.118.

[15] Anna Snaith, ‘”Little Brown Girl” in a “White, White City”: Una Marson and London, Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, 27:1 (2008), 93-114, p.97.

[16] Una Marson, ‘Kinky Hair Blues’ in The Moth and the Stars, p.91.

[17] Honor Ford-Smith, ‘Una Marson: Black Nationalist and Feminist Writer’, Caribbean Quarterly, 34:3 (1988), 22-37, p.29.

[18] Donnell, p.120.

[19] Ibid., p.149.

[20] Jarrett-Macauley, p.153.

[21] Edmund Kamau Braithwaite, History of the voice: The development of nation language in Anglophone Caribbean poetry (New Beacon, 1984), p.87.

[22] Jarrett-Macauley, p.167.

[23] Ibid, p.214.

[1] Delia Jarrett-Macauley, The Life of Una Marson,1905-1965 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998). p.5

[2] Talking it Over broadcast 11th July 1940 in Jarrett-Macauley, The Life of Una Marson 1905-1965

[3]Alison Donnell, ‘Una Marson: Feminism, Anti-Colonialism and a Forgotten Fight for Freedom’, in West Indian Intellectuals in Britain, ed, by Bill Schwartz (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003), p.114.

[4] Jarrett-Macauley, p.30.

[5] Donnell, p.116.

[6] Una Marson, ‘Editorial’, The Cosmopolitan: a monthly magazine for the business youth of Jamaica and the official organ of the Stenographer’s Association, Vol. 1 No.1 (May 1928), p.5. in Imaobong D. Umoren, ‘This is the Age of Woman’: Black Feminism and Black Internationalism in the Works of Una Marson, 1928-1938)’ History of Women in the Americas, 1:1 (April 2013), pp.50-73.

[7] Jarrett-Macauley, p.43.

[8] Ibid.

[9] The Daily Mail, Tuesday July 25th 1933.

[10] Jarett-Macauley, p.53.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Umoren, p.51.

[14] Donnell, p.118.

[15] Anna Snaith, ‘”Little Brown Girl” in a “White, White City”: Una Marson and London, Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, 27:1 (2008), 93-114, p.97.

[16] Una Marson, ‘Kinky Hair Blues’ in The Moth and the Stars, p.91.

[17] Honor Ford-Smith, ‘Una Marson: Black Nationalist and Feminist Writer’, Caribbean Quarterly, 34:3 (1988), 22-37, p.29.

[18] Donnell, p.120.

[19] Ibid., p.149.

[20] Jarrett-Macauley, p.153.

[21] Edmund Kamau Braithwaite, History of the voice: The development of nation language in Anglophone Caribbean poetry (New Beacon, 1984), p.87.

[22] Jarrett-Macauley, p.167.

[23] Ibid, p.214.