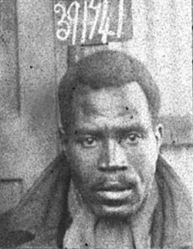

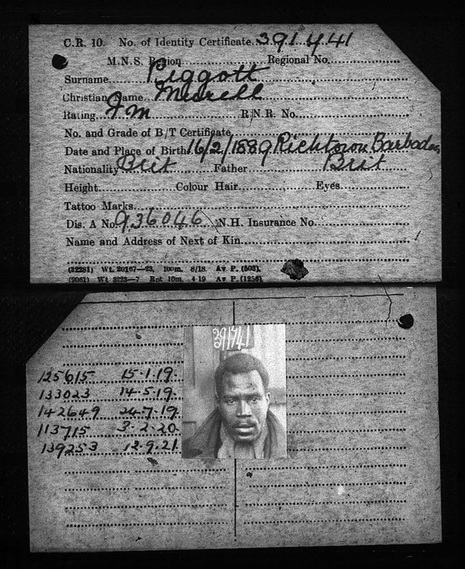

Murrell Piggott was born in Barbados on 16 February 1889. The details of his early life are unclear, however by 1917 he had moved to Britain and was employed in the maritime sphere. His seafaring life enabled him to travel to Europe as well as North and South America, and possibly to other continents around the world. In the summer of 1917 he was engaged at Lisbon to work the passage to Buenos Aires and then back to Liverpool on board the Amazon. The crewing list for this vessel advised that his last permanent address was 232 Bute Road, Cardiff.[1]

Piggott’s seaman’s pocket indicates that he worked as a sailor on board various British vessels between 1919 and 1921.

Piggott’s seaman’s pocket indicates that he worked as a sailor on board various British vessels between 1919 and 1921.

|

His position on board a steamship, like the majority of Black sailors, was in the engine room of the vessel. Piggott’s occupation was listed as a Fireman therefore his role was to tend the fire to maintain the successful running of the steam engine.

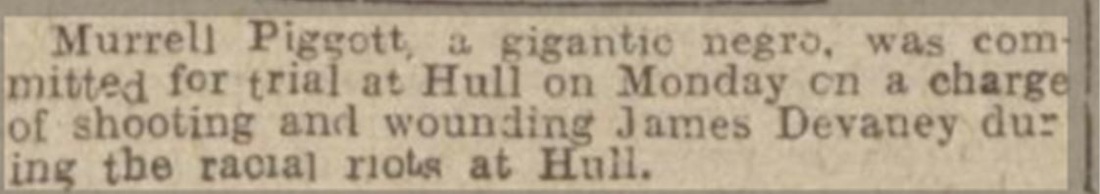

It is probable that employment opportunities brought Piggott to Hull in the summer of 1920, as his permanent address was still listed as Cardiff when the race riots began in the city. Piggott was involved at the outset of the rioting and was charged with unlawfully wounding James Devaney. Newspaper articles differ with regard to the details that led to the Black sailor’s arrest. Some advised readers that Piggott had seen a mob of white men kicking a Black child in the street before they had turned on him. However, others commented that Piggott had been chased from a public house when a struggle developed and his firearm was accidently fired twice. In the subsequent days after Piggott’s arrest he remained in jail because he had no friends in the city and no means to pay bail.[2] Piggott’s trial was on 13th July at York Assizes. His defence was that he did not fire at anyone specifically and his intention was to scare, not wound any of the mob. He believed that the men were going to lynch him and advised that had been badly bruised during the altercation. Despite his plea of self-defence, the judge, Justice Greer declared that, ‘people, whether black or white, must be taught that in this country it is unlawful to go about with firearms and fire indiscriminately about the street.’[3] Thus Piggott was sent to prison for nine month's hard labour. When he was released, he returned to his profession as a sailor but no evidence has yet been found to suggest that he came back to Hull. |

Click HERE to go to extracts about the Hull Riots from Jaqueline Jenkinson's book Black 1919: Riots, Racism and Resistance in Imperial Britain (Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2009)

Click HERE to go to a clipping about the Hull Riots from the Hull Daily Mail, June 1920.

Click HERE to go to a clipping about the Hull Riots from the Hull Daily Mail, June 1920.

Footnotes

[1] The National Archives: Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Inwards Passenger Lists.; Class: BT26; Piece: 637; Item: 45

[2] Hull Daily Mail, 28 June 1920, p. 6.

[3] Hull Daily Mail, 14 July 1920, p. 4.

[1] The National Archives: Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Inwards Passenger Lists.; Class: BT26; Piece: 637; Item: 45

[2] Hull Daily Mail, 28 June 1920, p. 6.

[3] Hull Daily Mail, 14 July 1920, p. 4.