|

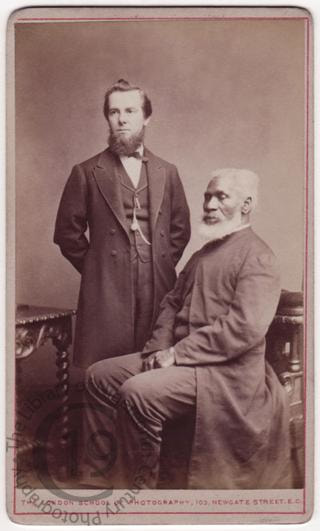

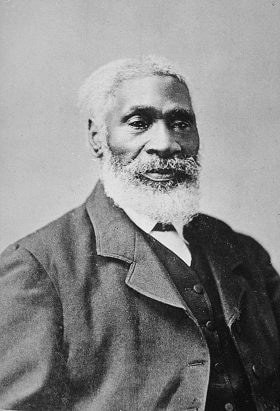

We're always delighted to receive correspondence from people who connect with particular stories and are inspired to investigate further or offer additions. Some of these exchanges remind us of the project's wide reach thanks to this website. Hannah-Rose Murray had previously written about the abolitionists who came to Hull and East Yorkshire for this project and it was the story of Josiah Henson that compelled her to contact us again some weeks ago. Our first story about Henson started for us with a photograph in Hull Museums Collection (Wilberforce House) and Hannah has been kind enough to supply the following extended blog post about him. "My Name is Not Uncle Tom!" Josiah Henson in Britain 1876-1877 In early March, an American colleague sent me a blog post on the African Stories website about Josiah Henson. The post was sparked by an incredible and previously unseen image which had been discovered by the project team in Hull: staring straight into the camera, the now-identified Henson consciously challenges the racist caption of 'Uncle Tom' underneath. In this image, and in life, Henson simultaneously exploited and fought against this symbol of white supremacy, and on several occasions entirely denounced what had become his nickname in Great Britain.

Henson visited Great Britain at least twice, first arriving in 1851. He was the only Black person to exhibit something at the Great Exhibition (wooden boards from his community in Canada) and this excerpt from his autobiography describes the experience in his own words: "At the Exhibition, because my boards happened to be carried over in the American ship, the superintendent of the American Department, insisted that my lumber should be exhibited in the American department. To this I objected. I was a citizen of Canada, and my boards were from Canada, and there was an apartment of the building appropriated to Canadian products. I therefore insisted that my boards should be removed from the American, to the Canadian Department. But the American said "You cannot do it. All these things are under my control. You can exhibit what belongs to you if you please, but not a single thing here must be moved an inch without my consent." I thought his position was rather absurd, but how to move him or my boards seemed just then beyond my control. Josiah Henson's third visit in 1876 sparked international fanfare and celebrity. In order to alleviate debt on his property, Henson sought out reformers and old abolitionist friends in Britain to help him raise money to overcome these financial difficulties. As a result of his famous association with Stowe's novel, he received over two thousand invitations to speak. He was a powerful orator, and newspaper correspondents praised his impressive stage presence. Most of the press paragraphs discussing him were reprinted almost verbatim from London to Liverpool, describing how Henson (the "original" Uncle Tom) "pictured [slavery] in a very effective way." In Sheffield for example, Henson gave two lectures in one day to thrilled audiences, and crowds of people turned up an hour and a half early. At another meeting, hundreds of people were turned away as there was not even standing room left to hear him speak, and his revised edition of his autobiography sold hundreds of copies. According to his white benefactor and editor John Lobb, Henson addressed over 500,000 people all over the country in less than a year. This was an incredible feat, as he was in his late 80s at this point. Although Henson was a successful author in his own right (the first edition of his narrative sold over two thousand copies in 1849, and over six thousand in the first three years before Stowe's novel was published) it was undoubtedly his association with the novel that prompted an invitation to meet Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle in 1877. Henson presented her with a copy of his autobiography and in return received the Queen's portrait. She then asked Henson and John Lobb to sign their names in an album in the castle. They toured the grounds and the state apartments, and left after roughly three hours. [1] Henson's Relationship with 'Uncle Tom' In order to achieve success on the British stage, Henson exploited his association with Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. His books were marketed as the story of "Uncle Tom" and hundreds of articles across the country addressed him as 'Tom' rather than Josiah Henson. This connection – and ultimately racist phrase – began to grate on Henson, and in several meetings across the country denounced he was Uncle Tom. In one meeting in Glasgow, he said: "Now allow me to say that my name is not Tom, and never was Tom, and that I do not want to have any other name inserted in the newspapers for me than my own. My name is Josiah Henson, always was, and always will be. I never change my colours." [2] While Henson's efforts would never be enough to change Victorian racism, he made an extraordinary impact on British society in general. Instead of focusing on the 'Uncle Tom' connection, we should remember Henson's activism, expressed fully in these quotes: "I look back from whence I came, and see by the eyes of my mind what you cannot see with your eyes, because you have not been there, and feel in my heart what you cannot feel, and I hope never will feel, and no one can feel it but the man who has had the iron through his own soul." [3] "[The Archbishop of Canterbury] expressed the strongest interest in me, and after about a half-hours conversation, he inquired, 'At what University sir, did you graduate?" "I graduated, your Grace' said I, in reply, 'at the University of Adversity." [4] Footnotes

0 Comments

|

Follow usArchives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed