|

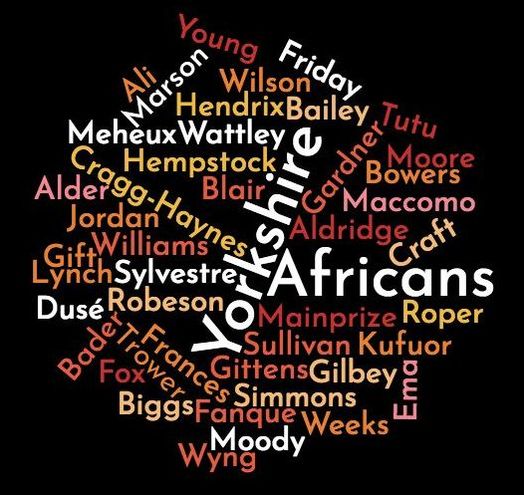

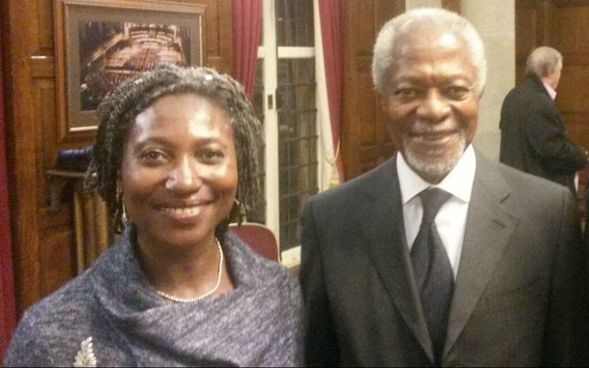

Image of Gifty taken by Emily Wilkinson and used with Emily's permission. We’ve had great success with this project since we began working on it in November 2015. We’ve uncovered some amazing stories, and covered a wealth of historic areas in Hull and East Yorkshire – from unknown black artists and entertainers, to exploring the maritime sphere. Our funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund ran out in January this year, so we’ve continued so far on a voluntary basis. This means that we need to scale back our releases from weekly to monthly. To reflect on what we’ve done so far, we sat down with project founder Gifty Burrows to get her thoughts on the African Stories in Hull & East Yorkshire project. We discussed what Gifty hoped to achieve, the local and global success of the project and exhibitions, and her plans for the future. What made you do the project? This project came about through a personal awakening about the historic importance of the transatlantic slave trade and an increased awareness of Black British history and the struggles Black people have had in claiming their place in British history. Having done nothing in compulsory education about either slavery or contemporary issues about race, this interest came because of my dual identity in being both British and African which seemed to be particularly relevant to me and it seems to other people in how they placed me in their consciousness. Certainly, issues about the historic and more recent overview about race still shape people’s perceptions and behaviour. Also, it struck me that as I live in a county synonymous with the abolitionist William Wilberforce, that we should consider what he did, rather than simply using his name. I thought there is a social responsibility in this region to recognise the effect of slavery on those of African descent in terms of displacement - which is the reality of the impact of slavery. Although slavery is mentioned, the purpose of this project is to demonstrate that there is more to Black presence and Black social history in Britain than slavery. Who is your team? After my initial idea in November 2015, I used two other people as my sounding board to see if some of my ideas and initial proposals would be workable, including holding a seminar and setting up a website with the help of Dr Carolyn Conroy (who went on to become our Web Manager). An application for Heritage Lottery Funding was submitted in March 2016 and funding was granted in May. We engaged a Lead Researcher in September which meant that we could go full steam ahead with the release of several stories each week. We have consistently been a team of three, myself as the Project Lead (unfunded), Dr Lauren Darwin as the Lead Researcher (funded) and latterly Thomas Burrows as the web Manager (unfunded). Many volunteers, transcribers and guest writers, some of whom contributed stories on several occasions, are all deeply appreciated for their support and are acknowledged on our Contributors list. How did you get the funding? We applied to Heritage Lottery Fund and were successful. At the time we had never done so before and didn’t have a view of it being difficult or otherwise. It was only later that we were able to reflect on what a good application we must have put in given the stiff competition at the time with all the other projects targeting Hull as the City of Culture. We also had other donations from other lesser partners all of whom are acknowledged on our contributions page. Are you with the university or the council? To clarify, although we have been supported from the Wilberforce Institute of Slavery and Emancipation (WISE) who were kind enough to host some of our events, this has not been a University of Hull project. We have also worked in partnership with both Hull City Council and East Riding of Yorkshire Council to bring two exhibitions to the public but again this has not been a council project. In addition, the James Reckitt Library Trust (Untold Stories) made the Contemporary Stories element of oral histories possible. However, this has been the idea of an individual who wanted to make a difference and was determined to show what was possible as an independent worker. I hope I have demonstrated what is possible for anyone to do even around a part-time job such as mine as an educationalist. How have you done all this with only the three of you? We were all passionate about the project and have a genuine interest in the subject. We also felt the need to get these wonderful stories out. Our output has been so frequent because of the wealth of stories there to tell. There was huge excitement with every new discovery and it felt good to be able to share this at regular intervals. How did you find the stories? The older stories were teased out by Lauren through her meticulous research skills. The family stories were a combination of archival research, supported writing and editing or self-written pieces. Where a family has had direct involvement with a story, we get them to sanction what is included, especially where we bring the story up to the modern day. How did you get the people to do the oral histories? A few people were approached initially and others became a part of it by association or recommendation. I always contacted the participant to explain the purpose of the project and what form the oral history would take. It was imperative that the participants felt comfortable about their contribution to this part of the project and it was made clear that they would have some control in the final output. It was crucial that they were not given a trial run of the questions and certainly those in the early days did not know what they would be asked. Some of those participating later on were told that examples previous oral histories could be found on our website and it was left to them if they wanted to listen; many chose not to so that they could come to it fresh. The questions were varied to avoid rehearsed answers. Although we engaged Jerome to conduct the interviews, I was keen to shape the direction of the questions and was present throughout. This helped to build the trust between myself and often a stranger. Undoubtedly the participants were reassured and had confidence in the fact that I readily understood some of the strands that came out in the conversations. The process was enriching for the three of us in the room. The participants felt positive about sharing their stories and were passionate in their desire to have their stories told and have their presence acknowledged as part of the wider project. A frequent initial comment was that they felt that their lives were ordinary and that they themselves were not particularly remarkable and yet they came out with memories and views that they hadn’t thought they knew or considered before. For many participants it became a journey of self-discovery as, it made them think more deeply about various points in their own lives and prompted a discussion about their own family histories. Some said that it made them ask questions and actively listen to the responses they were given; something which doesn’t always happen in the familiarity of family life. There was great reward in hearing feedback from others especially from the transcribers who learnt about some the more difficult and unjust experiences for people of African descent at very close quarters. It gave them an insight which would otherwise be beyond the communities they engaged with. How can people contact the project? The project website is still live and we can be contacted through this website, Facebook and Twitter. Is it still carrying on? Yes! We didn’t know what we would find, how many lives would be re-discovered or how many people would want to engage and have their presence acknowledged but what a rich pool – there is still much more to include. However, regular output takes funding and as that came to an end at the start of this year, we need to scale back as we continue working on a voluntary basis. This means that we will try and release a story regularly - monthly if we can - but we welcome help on that. So please share your family stories, offer ideas of anyone you come across, and let us know of anyone who might be interested to engage. This project has proved to have made a huge wave in the pond, not just the ripple we initially thought we would get. British Black history is often forgotten or consigned to the background except when Black History Month pops up in October and then it is too often peppered with notable people from America. This focus on British Black history is rarely done and we are proud to have broken new ground in what we have achieved. It’s a great resource, how come it’s free? We take the view that as educators, we do not see education as business. Learning benefits us all. Have you got schools involved? When we designed the project, it was important to us that schools should engage and could have the opportunity to be able to use the bank of resources freely. We have had eight events to date directly relevant to schools and at each one we have actively encouraged schools to participate. Where possible, we have tried to make schools aware of the website, exhibitions and the current study pack. How come nobody has done this before? I don’t know… perhaps because it was a dip into the unknown; it took effort to get started, to do it, there was no guarantee of success? How do you know what the impact has been? We have had direct feedback via the website, many people visit the pages with regular viewings. We know of other people doing similar projects elsewhere. We have been asked for advice. We have had contact from academics wanting information about certain aspects which we have covered. We have had significant media interest. We have been invited to several conferences. We have had direct contact from people in Malawi, Ghana, New Zealand, Australia, France, the USA and many cities in Britain. What part did you play in the project? I have driven the project and made sure that momentum is not lost. Stories need to be coordinated, followed up and nurtured, and need much support for them to become fully fledged. It takes more time and input than I anticipate. I have been exceptionally fortunate to have had excellent support in our tiny team. Did it help that you are African? Yes, there is an advantage in having a deep understanding of the experiences of the people in many of these stories. There are very few occasions being Black in Britain is seen as an advantage so it is certainly good to have the opportunity to celebrate difference. Do you think this will make any difference to those with negative views about diversity? No. Some people are resistant to ideas other than their own especially if it has been set through years of reinforcement. It is also easier for them not to have their beliefs challenged – thinking takes effort and change can be seen as impossible. The self-absorbed navel gazers see the world only in relation to themselves and this project is about looking out and seeing underneath the obvious…that is too much of a challenge for many. What would you have done differently? I would have extended the budget. I was very fortunate in being able to call on a lot of favours and good will to get things done. I would have also put in enough in the budget to pay myself! I also wish I had the personality to be less exacting in my standards. I am grateful that those I worked with understand that I am driven by a need to work for a common good. How did you overcome resistance or scepticism to the project? It perhaps helped a little that I had experienced success in my previous project of lighting the Wilberforce monument and gilding the abolition scroll. With that behind me I had the confidence to tackle the initial scepticism that was forthcoming when we first embarked on the project. There were some people in the city who felt deeply that there would be a limited pool of material to draw upon and that the project would not be successful. As we accessed more and more stories and the publicity gradually grew that instilled an even greater level of self-confidence to go on and prove the doubters wrong. In the early days I occasionally wondered if the sceptics would be right, I worried that the project would have no substance, but I felt strongly enough to try anyway. I suppose I’m frustrated by people who are too ready to accept things as fact without questioning anything. Logic told me that what traditional history taught us couldn’t be right – I just hoped that that conviction applied in this less diverse part of Britain too. What do you want to do next? I would like to manage another historic project and I’m looking for opportunities to take on my next challenge. As a strong, successful team we are happy to advise and take on consultation work. Exhibition now on!

The Our Histories Revealed Beverley exhibition is still on and will run until 30 June so catch it if you can. We've had some great comments from visitors so far:

0 Comments

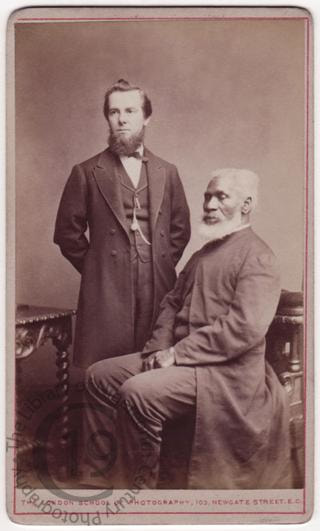

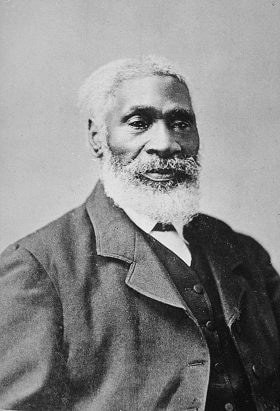

One of the fascinating aspects of this project is the way in which stories that have featured on the website stimulate further contributions as more information becomes available. The story of the Weeks family is one of the more widely known stories locally and features in our current exhibition at the East Riding Treasure House. Through his own contacts Richard Weeks has gained a further insight into the exploits of his father Fred during the Second World War from Caroline Gaden, the daughter of Ron Ford who had been his war-time colleague. Both Ron and Fred appear in the photograph opposite of the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) "Ferry Group 7" standing in front of a Mosquito aeroplane, probably taken at their base in Sherburn in Elmet. Fred had previously been involved in a fatal plane crash in April 1940 that killed 3 whilst working as a civilian flight engineer for Blackburn Aircraft Co, in Brough whilst testing a prototype flying board, the B20. Fred went on to join the ATA in 1942 as a flight engineering officer. The ATA were known as the Ancient and Tattered Airmen (or women) as most had been rejected by the RAF. Ron Ford was born in Hovingham, North Yorkshire and flew from an early age and won a flying scholarship. Ron joined the ATA as a pilot in July 1942 and met Fred almost straight away during training in Luton as described below: "Initially Ron was posted to the Elementary Flying Training School at Barton near Luton. Accommodation was hard to find and when he arrived by train he couldn’t find a bed so he went to the Police Station and asked for help. An officer refused to put him up in the cells and took him to some digs. Ron was nonplussed when the man who opened the door was of African extraction (Fred Weeks), he had never met a person with a different coloured skin to his own, but he ended up happily staying for the few weeks he was posted there." [1] After the initial training the two men worked together at their base in Sherburn in Elmet. In Ron Ford’s logbook the first mention of Fred being Ron Ford’s Flight Engineer is 8th September 1944 when the two of them flew a Halifax bomber from York to Hawarden in Wales. The majority of active airfields were in the east of the country and this flight would have been a damaged bomber being ferried from an active airfield to the safe side of the UK for repair. In reverse they flew new or repaired aircraft back saving "real" pilots for active service. Their base was Sherburn in Elmet and they had known each other since training in 1942. In total there are 18 flights logged as working together. A fascinating insight into their personal chemistry is from the following extract recounted by Caroline Gaden: "Freddie Weeks was his flight engineer. His father was African and his mother was English. Despite Ron’s reaction to his Luton billet he was happy to work with Fred and the two became great friends. Fred had survived a fire and crash with another pilot in a Catalina. His parachute had the release pins blown out so Fred couldn’t pull the pin to get it to open. Luckily for him the small ‘chute did open and pulled the big one with it and he survived. Fred refused to sit up front if the weather was ‘duff’. He’d retire to the back of the plane because he didn’t want to see himself die. Fred and Ron remained friends after the war and socialised together until Ron emigrated to Australia to be with his grandchildren, he died in 1999 aged 87. As an additional insight into the local war time experience for people of African descent, Ron’s daughter Caroline Gaden has given permission to quote her mother’s own observations: "I think initially there was very much a city v country divide ... rural folk had far less likelihood of meeting migrants from other countries, I'm sure for city folk it was far more common and I do wonder if the war actually helped break down some of the barriers ... everyone was in it together and bombs did not discriminate. I would think that the more industrialised areas in cities with cotton and woollen mills, armament and aeroplane factories and other 'war needed' vehicles would have much greater integration ... but did they socialise or did they head their separate ways after work ... I really don't know. But everyone shared the fear and food and sing-songs as bombs rained down." Caroline herself adds: "…re your father (Fred Weeks) selling the agricultural machinery... I think farmers are a canny lot, they would have been concentrating on what the equipment could do for them. In addition the war did do a lot to break down barriers.... some people put them straight back up post-war but many recognised the contribution made by others... there was probably more antagonism (for want of a better word) or less trust directed towards people who had lined their own pockets during the war or who had found a cushy job away from the bombs and bullets. People who served, of all shapes, sizes, creeds and colours were recognised for their service and given the respect and trust they had earned. Thank you to Richard Weeks and Caroline Gaden for sharing their memories. We're always delighted to receive correspondence from people who connect with particular stories and are inspired to investigate further or offer additions. Some of these exchanges remind us of the project's wide reach thanks to this website. Hannah-Rose Murray had previously written about the abolitionists who came to Hull and East Yorkshire for this project and it was the story of Josiah Henson that compelled her to contact us again some weeks ago. Our first story about Henson started for us with a photograph in Hull Museums Collection (Wilberforce House) and Hannah has been kind enough to supply the following extended blog post about him. "My Name is Not Uncle Tom!" Josiah Henson in Britain 1876-1877 In early March, an American colleague sent me a blog post on the African Stories website about Josiah Henson. The post was sparked by an incredible and previously unseen image which had been discovered by the project team in Hull: staring straight into the camera, the now-identified Henson consciously challenges the racist caption of 'Uncle Tom' underneath. In this image, and in life, Henson simultaneously exploited and fought against this symbol of white supremacy, and on several occasions entirely denounced what had become his nickname in Great Britain.

Henson visited Great Britain at least twice, first arriving in 1851. He was the only Black person to exhibit something at the Great Exhibition (wooden boards from his community in Canada) and this excerpt from his autobiography describes the experience in his own words: "At the Exhibition, because my boards happened to be carried over in the American ship, the superintendent of the American Department, insisted that my lumber should be exhibited in the American department. To this I objected. I was a citizen of Canada, and my boards were from Canada, and there was an apartment of the building appropriated to Canadian products. I therefore insisted that my boards should be removed from the American, to the Canadian Department. But the American said "You cannot do it. All these things are under my control. You can exhibit what belongs to you if you please, but not a single thing here must be moved an inch without my consent." I thought his position was rather absurd, but how to move him or my boards seemed just then beyond my control. Josiah Henson's third visit in 1876 sparked international fanfare and celebrity. In order to alleviate debt on his property, Henson sought out reformers and old abolitionist friends in Britain to help him raise money to overcome these financial difficulties. As a result of his famous association with Stowe's novel, he received over two thousand invitations to speak. He was a powerful orator, and newspaper correspondents praised his impressive stage presence. Most of the press paragraphs discussing him were reprinted almost verbatim from London to Liverpool, describing how Henson (the "original" Uncle Tom) "pictured [slavery] in a very effective way." In Sheffield for example, Henson gave two lectures in one day to thrilled audiences, and crowds of people turned up an hour and a half early. At another meeting, hundreds of people were turned away as there was not even standing room left to hear him speak, and his revised edition of his autobiography sold hundreds of copies. According to his white benefactor and editor John Lobb, Henson addressed over 500,000 people all over the country in less than a year. This was an incredible feat, as he was in his late 80s at this point. Although Henson was a successful author in his own right (the first edition of his narrative sold over two thousand copies in 1849, and over six thousand in the first three years before Stowe's novel was published) it was undoubtedly his association with the novel that prompted an invitation to meet Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle in 1877. Henson presented her with a copy of his autobiography and in return received the Queen's portrait. She then asked Henson and John Lobb to sign their names in an album in the castle. They toured the grounds and the state apartments, and left after roughly three hours. [1] Henson's Relationship with 'Uncle Tom' In order to achieve success on the British stage, Henson exploited his association with Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. His books were marketed as the story of "Uncle Tom" and hundreds of articles across the country addressed him as 'Tom' rather than Josiah Henson. This connection – and ultimately racist phrase – began to grate on Henson, and in several meetings across the country denounced he was Uncle Tom. In one meeting in Glasgow, he said: "Now allow me to say that my name is not Tom, and never was Tom, and that I do not want to have any other name inserted in the newspapers for me than my own. My name is Josiah Henson, always was, and always will be. I never change my colours." [2] While Henson's efforts would never be enough to change Victorian racism, he made an extraordinary impact on British society in general. Instead of focusing on the 'Uncle Tom' connection, we should remember Henson's activism, expressed fully in these quotes: "I look back from whence I came, and see by the eyes of my mind what you cannot see with your eyes, because you have not been there, and feel in my heart what you cannot feel, and I hope never will feel, and no one can feel it but the man who has had the iron through his own soul." [3] "[The Archbishop of Canterbury] expressed the strongest interest in me, and after about a half-hours conversation, he inquired, 'At what University sir, did you graduate?" "I graduated, your Grace' said I, in reply, 'at the University of Adversity." [4] Footnotes

This Saturday (5 May) we open our second exhibition at Beverley's East Riding Treasure House which runs until Saturday 30 June.

After the tremendous success of last year's exhibition in Hull, our latest opportunity to showcase the projects findings will have a greater focus on the people of African descent who visited, lived or worked in East Yorkshire between 1750 and 2007. We have a mix of our most popular releases from last year as well as some newer stories on display. Additionally, to complement the exhibition, we have a free study pack which can be collected from the Treasure House during your visit. The exhibition will feature amongst others the Black servicemen who were based in Cottingham, Filey and Pocklington during the Second World War, the activists and abolitionists who came to the East Riding to speak out against slavery and to campaign for equality and the accomplishments of Black actors, entertainers, sportsmen and entrepreneurs in our area. During the exhibition period, we're hosting three events which include:

Head to the Events page for more details or if you would like to book a place at one of these events. |

Follow usArchives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed