Between 1900 and 1950, over 120 people of African descent appeared in court as the perpetrator, victim or witness of a crime committed in Hull or East Yorkshire. The focus of this section is to highlight the lives of Black men and women through their interactions with the criminal justice system. It shows that by analysing the context in which crimes were committed, we can gain a better understanding of the wider social and economic climate which was endured by people of African descent living in this region during the first half of the twentieth century.

Economic, Political and Social Circumstances

The first half of the twentieth century was a turbulent period for people of African descent living in Hull and East Yorkshire. War, economic uncertainty, unemployment, racism and poverty made Black men especially vulnerable to the legal system. Although, Clive Emsley has argued that it is 'difficult to link the broad pattern of crime statistics to the economic, political and social changes and upheavals of the century … to produce an explanation for criminal behaviour that fits easily and logically with other social phenomena' [1] in terms of crimes committed by people of African descent in Hull and East Yorkshire, it can be argued that a significant number can be contextualised by specific social and economic events.

The first half of the twentieth century was a turbulent period for people of African descent living in Hull and East Yorkshire. War, economic uncertainty, unemployment, racism and poverty made Black men especially vulnerable to the legal system. Although, Clive Emsley has argued that it is 'difficult to link the broad pattern of crime statistics to the economic, political and social changes and upheavals of the century … to produce an explanation for criminal behaviour that fits easily and logically with other social phenomena' [1] in terms of crimes committed by people of African descent in Hull and East Yorkshire, it can be argued that a significant number can be contextualised by specific social and economic events.

Prior to the outbreak of the First World War most people of African descent who came to Hull were sailors. In the first decade of the twentieth century a broad variety of crimes were committed, the majority of which were minor infractions such as drunkenness, breaking the peace, obstructing a police officer and other petty offences such as ‘exposing the most disgusting cards in the street.’[2] These crimes were not linked to particular instances of social or economic upheaval. However, there were cases of stealing which can be initially explained by poverty after relocation as well as lack of employment opportunities.[3] In the years immediately prior to the First World War, as complaints from white sailors began to circulate in the maritime sector, racial tensions started to bubble under the surface and the competition for jobs increased on board ships and at the docks, cases of fraud and stealing became more frequent, possibly reflecting the difficulty to find work.[4] Racial tensions abated during the First World War, as Black sailors from Africa and the West Indies became exceptionally useful as they joined the Merchant Marine.

|

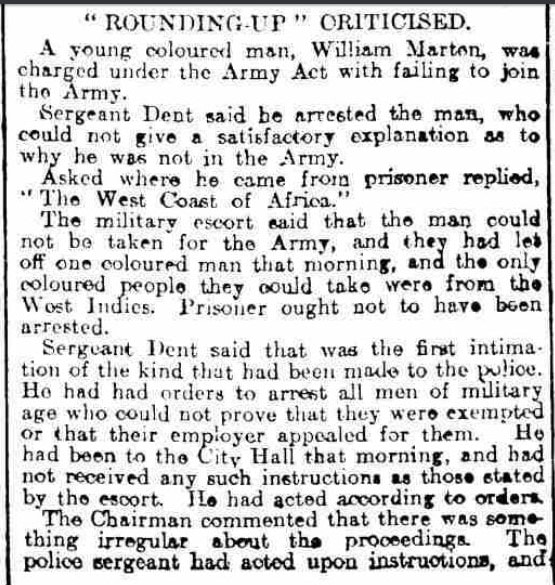

During the First World War, there was a national decrease in most crimes committed by adult males because a large proportion were in service. However, crimes relating to the military or national security inevitably increased. [5] Across Britain, men who were age-appropriate British subjects appeared before the courts under the Army Act for not joining up. In Hull, several men of African descent were arrested and given to an escort to ensure they pledged their service. However, it was not the case that they had an aversion to fighting for Britain during the war; instead, they found that information was withheld from them or they were turned away from the City Hall when they tried to voluntarily join the army. There are multiple examples of men such as John Wesley, a 20-year-old West Indian, who was charged in September 1916 and forced to join the army. He told the court that he had no idea that he had to join up but would happily do so to serve the country.[6] A year later, in June 1917, William Jackson, a Black British subject was charged with being an absentee after being unable to give a plausible reason for why he wasn’t in the army. The prisoner suggested that he had been to the City Hall but could not get any information. He was fined 40 shillings and handed to an escort

|

to take him to join up.[7] His story echoes that of Henry Glover, who insisted that he had been turned away from Hull City Hall when trying to join the Army (read Glover’s story here). The most bizarre case was that of William Marten, a native of the West Coast of Africa who was arrested in Hull on 13 September 1916 (see above). He was also ordered by the court to serve; however, the military escort told the magistrate that the dockworker could not be accepted into service because he was not from the West Indies. This caused confusion since it was believed that all men who were British subjects and were of military age had to go to war unless they were deemed exempt for legitimate reasons.[8] It has not been determined whether Marten joined the Army or not.

The Alien Order Act which was enforced during the First World War limiting the movement of ‘foreigners’ also brought men of African descent before the court. One example, among many was Charles Brouzwell, an African American, who was fined in September 1918 for leaving Hull and travelling to Cardiff without informing the authorities. He insisted that he had been out of work and received a wire telling him to come to the Welsh port and join a ship. He was in such a hurry that he forgot to notify the correct people.[9]

After the war, the social and economic situation worsened for people of African descent living in Hull and East Yorkshire. The Aliens Restriction Act and ‘colour bar’ which placed limitations on the employment opportunities and rights of ‘immigrants’ already living in Britain, severely affected Black sailors who had settled in Hull despite many of them possessing British citizenship. As a result, a large proportion were plunged into poverty and were unable to gain employment for several months. During this period Black men typically did not or could not claim from the state and thus men like Charles Goldbourne Steede were accused of making money through immoral means.

|

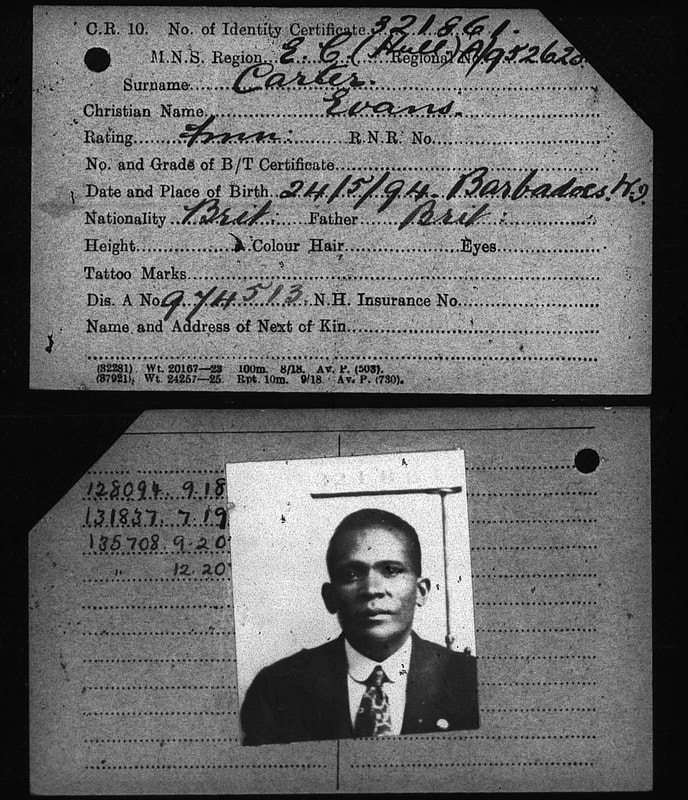

This period was plagued by economic instability and appalling instances of racism. In the 1920s, race riots broke out (read information on the Hull’s race riots here) and racial abuse became commonplace. In January 1920, Abraham Elion was walking home with a white female acquaintance. A man followed the couple making comments about how she was “Going with a Black” which at the time was source of aggravation for white men. Elion told the man to leave them alone and when he would not, he become angry and used profanities to show his annoyance. A police officer than arrested Elion for his use of bad language. Shocked, he questioned why the other man had not been arrested and asked “Why are we to be punished like this … we cannot go about anywhere. If you don’t want us, send us out of the country.”[10] Elion was fined 15 shillings for his offence, although he had clearly been provoked. Racial abuse and fear of physical violence, must have been the cause of some men committing crimes. In the spring of 1924, Barbadian Evans Carter, stabbed John Henry Armitage to death.[11] He was apprehended and appeared at Leeds Assize court on 10 May originally charged with wilful murder which was reduced to manslaughter because of the details of the crime. On the night of 21 April, Thomas Armitage, a boiler scaler from Adelaide Street and his brother visited the Wittington Inn on Commercial Road. They did not leave the establishment until it closed and

|

were highly intoxicated. On their way home they saw two Black men and three women, one of whom was also of African descent, near Perseverance Place. An offensive remark was made by the brothers as they passed the group and a row erupted resulting in Armitage striking Carter with a full glass bottle which smashed and severely cut his head. In a blind rage, hurt and bleeding, he followed Armitage and stabbed him several times. As the crime had occurred as a reaction to racism, Carter received a more lenient sentence.[12] During the case the defence pointed out that the trouble was caused by the ill feeling which was growing in the city regarding Black men marrying white women.[13] The defence also claimed that Carter had taken the knife from Armitage in the original row. In terms of character, the court was informed that the Barbadian had lived in Hull for several years, had been in the army and had shown nothing but exemplary conduct prior to this incident.[14] Carter pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 12 months hard labour. As the crime had been initiated by racism, before the Judge delivered the sentence he said “Evans Carter, you have pleaded guilty to manslaughter, and I want you to understand that the sentence I am about to give you is precisely the same as I would have given a white man in similar circumstances. Justice Avery went on to state that the use of knives was not permitted in Britain and while he understood that the perpetrator had been provoked, it was not acceptable.[15]

|

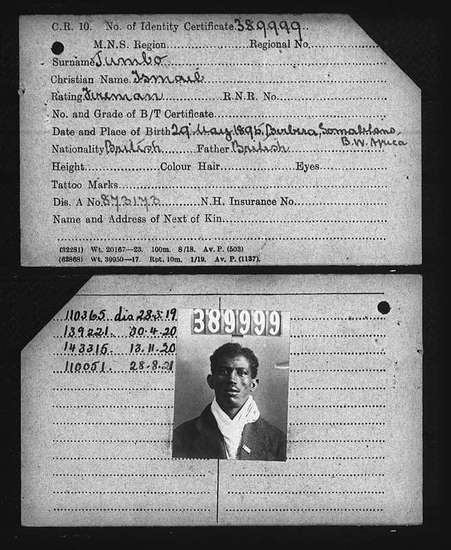

In the 1930s, Britain was in the midst of an economic depression. Although national unemployment soared, reaching around 22% (in northern parts of England, Scotland and Wales it was far higher), in 1933 crime rates stayed relatively low and up until the mid-twentieth century there were fewer links between crime and economic or political circumstances.[16] Instead racism continued to dominate the narrative for people of African descent in Hull and East Yorkshire, negatively influencing the conviction and sentencing process of criminal justice. Despite a concentration of crime reports, which included racial abuse in the 1920s, racism was omnipresent until (and beyond) the mid-twentieth century. In the early 1930s Ismail Jumbo was living in a house in Burton Street, Hull. Despite his lengthy time in the city, on 20 August 1931, he appeared in court on a recommendation for deportation under the terms that he was an ‘undesirable alien,’ after being found guilty of stealing a metal watch during a scuffle.[17] The defence argued that Jumbo was a British subject because he was from British Somaliland and he had only been reported to the Alien’s Department because he was a coloured man. Jumbo was not only a British citizen by birth, he had also risked his life for Britain in the First World War and nearly died when his ship was torpedoed in 1916.[18] In the court his defence lawyer showed copies of his marine certificates which testified to his citizenship. The Stipendiary Magistrate ruled that, ‘he did not think it would be safe to recommend Jumbo for deportation.’ He bound Jumbo over and fined the African seaman for his crime.[19]

|

|

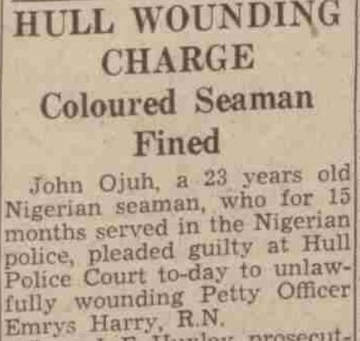

In December 1943, John Ojuh ‘who for 15 months had served in the Nigerian police’ pleaded guilty to wounding Emprys Harry. However, he insisted it was in self-defence. Ojuh told the court that he was in a pub with four sailors, one of whom called him a “nigger.” He told the man not to use that word but said there was no nastiness between the pair and they continued to drink together. Later, he had gone to a café, so he could get a meal, he saw the sailor whom had called him, and another man named Harry. During the meal, Harry had asked Ojuh “Why do you niggers mix with white men?” The Nigerian said that if Harry knew what that word actually meant he wouldn’t use it. Harry then lost his temper and grabbed Ojuh’s collar and threatened him while the other sailor pulled his hands behind his back. Ojuh pulled out his knife and stabbed Harry in the head and the hand. He then ran out of the café and was seen by a police officer throwing away the knife. Ojuh was caught and taken into police custody before being charged and ultimately sentenced to pay a fine of £2 and 2 shillings or serve 29 days in prison. The chairman of the bench, Mr J. F. Haller said that Ojuh had definitely been provoked but he should have known that it was wrong to use a knife on another person.[20]

|

Hull Daily Mail, 16 January 1947, p. 4

Hull Daily Mail, 16 January 1947, p. 4

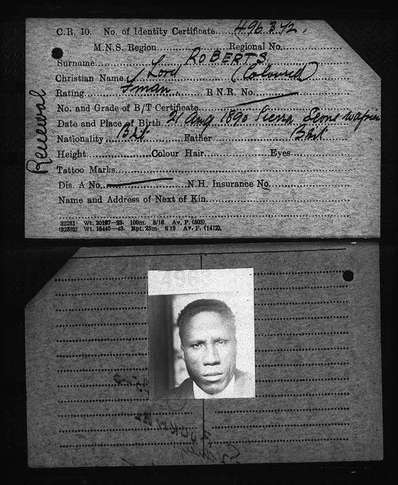

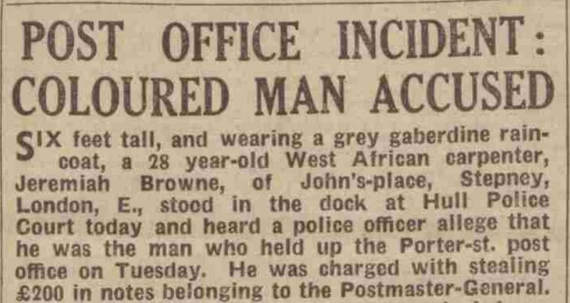

As well as being a factor in provoking criminal actions, institutional racism and prejudice about men of African descent also contributed to criminals being convicted when they were not necessarily guilty. For example, on 15 May 1920, Henry Roberts, a 25-year-old ship’s fireman, who lived at 6 Botanic Place, Hessle Road, appeared in court after being charged with striking Abraham Brammeld with a knife. However, although he had been found in possession of a blade insisted he had not carried out the attack pointing out that there was no blood on his knife.[21] In addition, while Roberts was identified by one witness, the other two witnesses could not pick him out of the police line-up.[22] Furthermore, on 14 January 1947, Porter Street Post Office in Hull was robbed at gun point. The man accused of the offence was 28-year-old carpenter Jeremiah Browne. It was alleged that the West African had threatened three female members of staff and stole £200. After he had taken the cash, it was believed he ran and hid in a house in Rifle Terrace. When discovered, Brown did not have a revolver in his possession nor the stolen cash. He only had a return ticket to London on his person when arrested. Mr Stephen the prosecutor accused Browne of hiding the gun and money in one of the many bombed-out buildings because he had a rubber band in his pocket which could have been wrapped around one of the bundles of notes. However, the carpenter insisted that there had been around a bundle of £50 in notes of his own money. Browne denied any knowledge of the theft and insisted that he had only travelled to Hull to visit a friend. Interestingly after he had been arrested, the West African had objected strongly to the identity parade since he claimed that all the men in the line-up were lighter skinned than him and thus it was not fair. In Browne’s defence Percival Stanley Bullard, the regional officer of the Colonial Office’s welfare department told the court that he was ‘an honest, respectable and industrious man.’[23] Brown was first bound over on condition he would returned to West Africa. However, he refused and thus was sentenced to three years penal servitude.[24]

Sadly, institutional racism still plagues the British justice system. The tragic death of Stephen Lawrence, and more locally Christopher Alder (read Christopher Alder’s story here) has showed that many reforms still need to take place before equality is achieved.

Sadly, institutional racism still plagues the British justice system. The tragic death of Stephen Lawrence, and more locally Christopher Alder (read Christopher Alder’s story here) has showed that many reforms still need to take place before equality is achieved.

The Crimes Committed

The crimes committed by people of African descent were typical of those which took place in other port cities such as Cardiff and Liverpool. They were property offences, violent crimes and minor infractions, all of which were usually committed by sailors or people living within the maritime quarter regardless of race or nationality.

It is important to note that very few women of African descent appeared in front of the regions courts as perpetrators. As with broader historical trends in criminal profiles, the offender was most commonly a young man. However, with minority groups the ratio of male to female offenders is more pronounced because of their migratory patterns.

The crimes committed by people of African descent were typical of those which took place in other port cities such as Cardiff and Liverpool. They were property offences, violent crimes and minor infractions, all of which were usually committed by sailors or people living within the maritime quarter regardless of race or nationality.

It is important to note that very few women of African descent appeared in front of the regions courts as perpetrators. As with broader historical trends in criminal profiles, the offender was most commonly a young man. However, with minority groups the ratio of male to female offenders is more pronounced because of their migratory patterns.

|

Property Offences

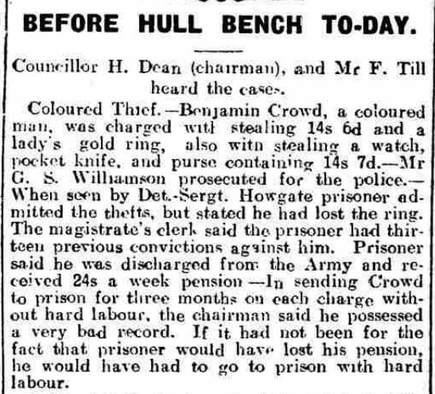

Property offences were prevalent in Hull and East Yorkshire throughout the early twentieth century. However, in times of economic instability or unemployment there seems to have been an increase in offenders of African descent. In May 1919, Peter Biggins, a dock labourer, stole two pounds of butter and five pounds of bacon which was the property of the Ellerman and Wilson line. Biggins was reportedly in need of the items owing to his ‘situation.’ When sentenced the magistrate said that he was sorry to see Biggins in such a position and owing to his previous good conduct his fine of 5 guineas was relatively lenient.[25] For those who showed remorse like Biggins, the courts would sometimes show mercy and try not to compound an individual’s economic plight by restricting the fine or not taking away future income. This can be seen in the case of Benjamin Crowd, who appeared in front of the Hull Police Bench on 3 October 1919 charged with stealing several items including a gold ring, watch, pocket knife and purse. Although, the prisoner admitted his |

crimes and that he had been charged 13 times previously, Crowd told the court that he was an army veteran and received 24 shillings per week presumably, so he would be shown leniency. The magistrate sentenced Crowd to three months in prison and inferred that he would have added hard labour to his sentence but that would have also meant a loss of his Army pension.[26] In other cases, the reasons behind why a person committed property offences are difficult to ascertain. Sometimes it may have been impulse, a misunderstanding or greed. Very few offenders of African descent appeared in front of the court on multiple occasions. Of course there were exceptions like Crowd and Frederick Harold.

In the 1920s, many men like Kwamina Annan Sey, who claimed to be the son of an African chief, confessed in court that stealing was a last resort. Although, the perilous situation of Black men eased somewhat in the 1930s, it was difficult for them to find work until the Second World War.

|

Violent Crimes

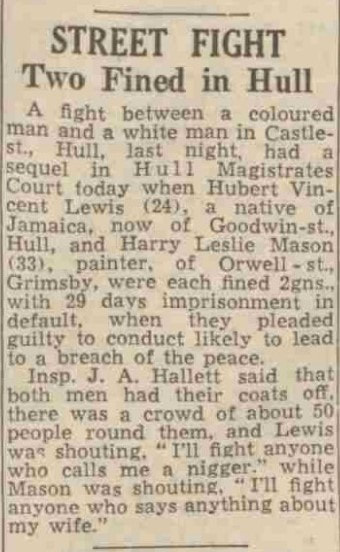

Sadly, in the early twentieth century, violence was an everyday part of life for those who lived in the poorest areas of port cities. Threats, street fights, bar brawls and domestic violence were prevalent among the working classes and commonplace within the maritime districts of Hull. Men typically preferred to sort out their disputes with their fists. For example, in November 1950 a crowd of 50 people gathered to view a street brawl on Castle Street, between 24-year-old Jamaican, Hubert Vincent Lewis, a resident of Goodwin Street and 33-year-old Harry Leslie Mason from Grimsby. The court heard that a heated exchange had taken place between the men, who had both removed their jackets. Lewis shouted “I’ll fight anyone who calls me a nigger” while Mason was bellowing “I’ll fight anyone who says anything about my wife.” The pair were arrested and pleaded guilty to conduct that was likely to breach the peace. They were fined two guineas or 29 days in prison.[27] However, while some men chose to use their fists to settle their differences others chose deadly weapons such as knives and revolvers. From the mid-nineteenth century, it was acknowledged that knife crime was prevalent in the maritime community. As Mick Macilwee has commented, sailors carried daggers, sheath knives, clasp knives or penknives which could transform ‘petty arguments into murder inquiries.’[28] In November 1908, an affray in which several ‘coloured men’ were fighting with knives at the Shipping Office, Posterngate, led to multiple arrests. One of whom was Egyptian Moha Sabh, who was charged with cutting and wounding marine fireman, Benjamin Jacquord. Ben Hardy, ‘a coloured man’ was also charged with assaulting Hugh Sterry. The fight seemed to revolve around employment opportunities.[29] In some cases, men of African descent did not need to use a knife or razor, they merely had to be accused of threatening behaviour like Nathaniel Calhoun. |

|

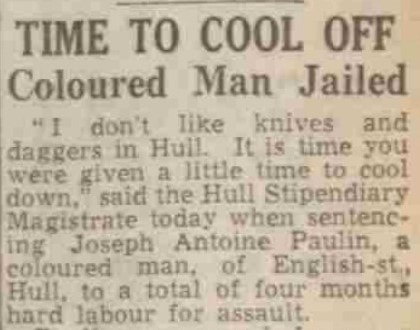

Knife crime was mentioned in reports throughout the first half of the twentieth century and seems to have been a particular issue with sailors rather than a specific racial phenomenon. In the 1940s, magistrates spoke out against the use of weapons in Hull. In May 1946, Thomas Bestman was sentenced to three months hard labour for stealing 10 shillings from Joseph Antoine Paulin. Both men were reportedly of African descent. The victim had told the court that Bestman had stolen money from him at knife point on 17 May.[30] As a result the attacker was sentenced to three months hard labour. However, two years after having his own brush with a knife, Paulin who lived at English Street was sentenced to four months hard labour for assaulting Adelaide Walton, Ernest Stonell and Henrietta Pomsingh in a house in Walker Street with the same weapon. The magistrate professed “I don’t like knives and daggers in Hull. It is time you were given a little time to cool down.”[31]

|

|

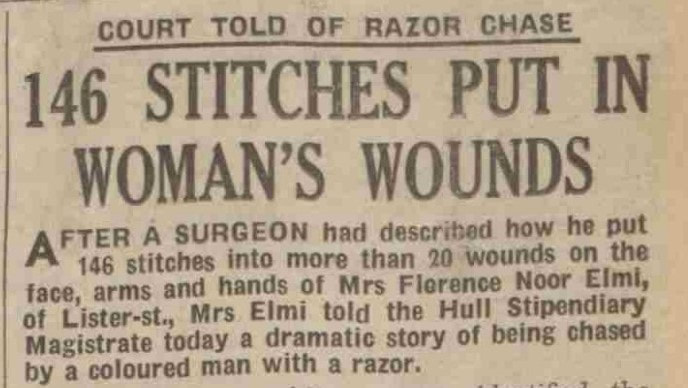

On occasion, deadly attacks took place in Hull’s maritime quarter which caused serious bodily harm on innocent individuals. In September 1949, Jamaican, Rupert Theodore Atkinson attacked Mrs Florence Noor Elmi, a white woman who ran a fish shop with her husband in Leicester Street, with a razor. The pair had possibly been having a relationship as he had given her gifts and taken a romantic interest in her. However, on 1 September, when she had been cleaning the windows of the fish shop, Atkinson had approached her, and she asked him to leave her alone, as she would be in trouble with her husband for conversing with him. Atkinson replied, “I am going to kill you. If I cannot have you then no one else shall.” The Jamaican clearly

|

saw her brush-off as a rejection and later forced his way into the fish shop and followed her through the kitchen where he attacked her with a razor.[32] In total she needed 146 stitches. Atkinson was arrested and pleaded guilty stating that he didn’t care if he received a sentence of 20 or 50 years, he committed the crime of wounding with intent to cause grievous bodily harm. Surprisingly, he was granted bail. However, he threatened Mr Elmi and was rearrested spending the time until his sentence in police custody. He was eventually taken to the York Assize Court for sentencing and received 7 years imprisonment.[33] Crimes of passion were committed frequently within the maritime sector with terrible consequences as in the case of Prince Eugene Bullen and Ada Saltus, and George Emanuel Michael and Theresa Hempstock.

Alongside knives and razors, guns also sometimes found their way onto the streets around the port. This was particularly evident in the 1920s. In May 1920 Senegalese ship’s fireman, Alphonso Dragner was tried at the Yorkshire Assize courts for shooting James Thomas Portz in Mytongate. During his trial, the African insisted that the victim had called him ‘a black nigger’ but he was innocent, and his friend another man of African descent had fired the revolver.[34] Weapons were also found on some of the Black men arrested in the race riots. Again, firearms were present in the maritime community and were carried especially in the 1920s by men of African descent to protect themselves against racial violence.

Petty Offences

Alongside the more serious offences of stealing and violent crimes, people of African descent did appear in court for a range of petty offences. Whether they were more likely to be arrested because of their skin colour is difficult to ascertain but it is possible. In June 1917, Charles Williams, an Army veteran, was charged with obstructing the footway in Posterngate. He remarked, “We coloured people have no chance here; we are treated like dogs.” He went on to state that he had been discharged from the army around one week ago and was waiting for his wife when the officer came up to him asking how he was living. Williams said that he was living on his pension, so the police officer hit him and nearly knocked him over. The police officer denied these allegations and said Williams would not move from blocking the pavement.[35]

Alongside the more serious offences of stealing and violent crimes, people of African descent did appear in court for a range of petty offences. Whether they were more likely to be arrested because of their skin colour is difficult to ascertain but it is possible. In June 1917, Charles Williams, an Army veteran, was charged with obstructing the footway in Posterngate. He remarked, “We coloured people have no chance here; we are treated like dogs.” He went on to state that he had been discharged from the army around one week ago and was waiting for his wife when the officer came up to him asking how he was living. Williams said that he was living on his pension, so the police officer hit him and nearly knocked him over. The police officer denied these allegations and said Williams would not move from blocking the pavement.[35]

|

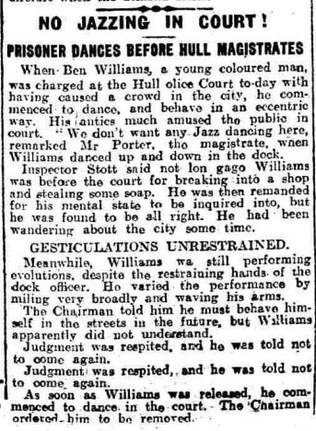

Another common petty offence, beside the use of profanities, resisting arrest, fighting and drunkenness, was ‘causing a crowd.’ This crime was committed in March 1920 by Ben Williams who was described as ‘a young coloured man’. While his case was being heard at Hull Police Court, it was reported that he began to dance and ‘behave in an eccentric way.’ His dancing was greeted with laughs and sniggers from the public spectators in the court. The magistrate advised Williams “We don’t want any Jazz dancing here.” However, the prisoner continued to dance in the dock. Williams had appeared previously in court for breaking into a shop and stealing some soap for which he was reprimanded so his mental health could be assessed. However, he was evaluated and found to be of safe mind although it was reported that he had been ‘wandering about the city for some time' While the evidence was given William’s continued to dance and although the chairman cautioned that he must behave in the future, when released, he danced out of court.[36]

|

Victims

On occasion Black men were attacked due to racial stereotypes. In the 1920s, there was a belief that all men of African descent carried a knife which led to various heated exchanges and sometimes violent attacks on innocent people. In June 1927, James Creighton who lived in Prior Street assaulted Charles Williams, ‘a coloured man’ of Warwick terrace, Warwick Street in Hull on Drypool Bridge.[37] Williams declared that Creighton shouted “Now, you black _______, have you a knife?”[38] To which he replied that he did not carry one, and when he went to walk away Creighton asked him why he didn’t go back to his own country. The defendant then struck him in the mouth. Creighton denied the charge of assault and alleged that Williams had previous threatened to stab him which is why when the pair met on Drypool Bridge and when the plaintiff had put his hand in his pocket, he believed he was reaching for a

On occasion Black men were attacked due to racial stereotypes. In the 1920s, there was a belief that all men of African descent carried a knife which led to various heated exchanges and sometimes violent attacks on innocent people. In June 1927, James Creighton who lived in Prior Street assaulted Charles Williams, ‘a coloured man’ of Warwick terrace, Warwick Street in Hull on Drypool Bridge.[37] Williams declared that Creighton shouted “Now, you black _______, have you a knife?”[38] To which he replied that he did not carry one, and when he went to walk away Creighton asked him why he didn’t go back to his own country. The defendant then struck him in the mouth. Creighton denied the charge of assault and alleged that Williams had previous threatened to stab him which is why when the pair met on Drypool Bridge and when the plaintiff had put his hand in his pocket, he believed he was reaching for a

|

knife. Creighton was bound over for 6 months.[39] Furthermore, on Boxing day in 1949, when a violent incident occurred in a Castle Street pub, Alan Samuels, who was described as a ‘coloured man’ by a Hull Daily Mail reporter, had argued with Victor Scott, a ships fireman from Hull. Samuels had apparently insulted one of Scott’s female friends which caused the two to have crossed-words. As Samuels was taking a drink, Scott hit him causing extensive wounds to his face. The wounds from this attack were so severe that Samuels needed an operation on his face and eye. However, Scott claimed self-defence as he informed the court that he believed Samuel was going to throw the glass at him - an unlikely scenario since the glass was against the victim’s face when he was hit. His plea was upheld in Hull’s police court on 12 January 1950 and he thus suffered no consequences of the attack much like Creighton.[40]

On rare occasions, the perpetrator, victim and witness were all of African descent. This was the case in October 1919, when Robert Williams, a 25-year-old ship’s fireman, appeared in court charged with wounding Petani Andrews by cutting his face with a razor. The altercation had taken place in the Robin Hood Hotel in Mytongate on 5 August in front of Lord Roberts, a Sierra Leonean sailor, who was questioned as a witness. Williams was found guilty and although he had already served three months in prison awaiting his trial, he was told he had to go back for a further 6 months as a deterrent for using a knife.[41]

|

Concluding Remarks

Although crime is a difficult subject and the exploration of criminality often casts a negative light, court records and reports are extremely useful for charting those who left no other trace of their life behind and whose stories therefore have been lost. In addition, in cases which were deemed unusual or the criminal was of interest, the records contain rich biographical data. For example, through an article in the Hull Daily Mail, readers learned that William McPherson, who was born in Norfolk, Virginia worked in the US Navy in his late teens. He then travelled to Britain in 1901 with the Walhalla Troupe, a comic opera group. With them McPherson visited Germany and stayed there for five years performing around the country. After the tour, McPherson returned to England but found it exceptionally difficult to find work so began singing in public houses. His profession eventually brought him to Grimsby where he settled and worked as a fisherman. However, he ended up in court on 15 November 1912, after stealing a pair of boots, he pleaded guilty and received a one-month prison sentence with hard labour.[42]

Crime data is vital to understanding the social and economic climate in which minority groups worked and lived in. In Hull, as in other port cities, both World Wars, unemployment, economic instability, poverty, fear and racism were all factors which contributed to a large volume of the crimes which were committed in the region.

Although crime is a difficult subject and the exploration of criminality often casts a negative light, court records and reports are extremely useful for charting those who left no other trace of their life behind and whose stories therefore have been lost. In addition, in cases which were deemed unusual or the criminal was of interest, the records contain rich biographical data. For example, through an article in the Hull Daily Mail, readers learned that William McPherson, who was born in Norfolk, Virginia worked in the US Navy in his late teens. He then travelled to Britain in 1901 with the Walhalla Troupe, a comic opera group. With them McPherson visited Germany and stayed there for five years performing around the country. After the tour, McPherson returned to England but found it exceptionally difficult to find work so began singing in public houses. His profession eventually brought him to Grimsby where he settled and worked as a fisherman. However, he ended up in court on 15 November 1912, after stealing a pair of boots, he pleaded guilty and received a one-month prison sentence with hard labour.[42]

Crime data is vital to understanding the social and economic climate in which minority groups worked and lived in. In Hull, as in other port cities, both World Wars, unemployment, economic instability, poverty, fear and racism were all factors which contributed to a large volume of the crimes which were committed in the region.

For more project information on individual criminal cases in the region see:

James Edward Philadelphia Moore

Charles Goldbourne Steede

Kwamina Annan Sey

Frederick Harold

Nathaniel Calhoun

Prince Eugene Bullen & Ada Saltus

George Emmanuel Michael & Theresa Hempstock

Henry Glover

Frederick Brown

Hull Race Riots

Recent Cases

Christopher Alder

David Oluwale

James Edward Philadelphia Moore

Charles Goldbourne Steede

Kwamina Annan Sey

Frederick Harold

Nathaniel Calhoun

Prince Eugene Bullen & Ada Saltus

George Emmanuel Michael & Theresa Hempstock

Henry Glover

Frederick Brown

Hull Race Riots

Recent Cases

Christopher Alder

David Oluwale

Footnotes

[1] Clive Emsley, Crime and Society in Twentieth-Century England (London: Longman, 2011), p. 24

[2] There are multiple examples of petty offence for a selection see the cases of: Samuel Stirrup, Hull Daily Mail (HDM), 3 June 1904, p. 4; William Pheonix, HDM, 24 November 1905, p. 6; James Richards, HDM, 23 October 1909, p. 2; Emanuel Victor, HDM, 27 December 1909, p. 6; Charles Williams, HDM, 7 September 1910, p. 3

[3] See the case of Price Makaroo, Driffield Times, 27 April 1907, p. 2 and Roland Stowe, HDM, 1 June 1912, p. 6

[4] See the case of: Arnold George Cummings, Hull Daily Mail, 3 June 1909, p. 4; Harrison Baily, Hull Daily Mail, 30 June 1909, p. 3; Ephraim Matthews, HDM, 8 February 1910, p. 5; Weldon Collins, HDM, 22 April 1914; Thomas Melgum (multiple stealing convictions) a selection include: HDM, 23 April 1912, p. 8; HDM, 25 October 1912, p. 5; HDM, 22 Oct 1914, p. 4,

[5] Clive Emsley, Soldier, Sailor, Beggarman, Thief: Crime and the British Armed Serviced since 1914 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 71-72

[6] HDM, 12 September 1916, p. 3

[7] HDM, 11 June 1917, p. 4

[8] HDM, 20 September 1916, p. 3

[9] HDM, 30 September 1918, p. 4

[10] HDM, 24 January 1920, 4

[11] There are various versions of events some newspaper articles advise readers that Carter followed Armitage to his sister’s house and stabbed her before him. However, this was not factored into the charges. See Hull Daily Mail, 30 April 1924, p. 7. Other articles include: Hull Daily Mail, 22, 24 and 29 April 1924.

[12] HDM, 10 May 1924, p. 6

[13] Ibid, p. 6

[14] Ibid, p. 6

[15] HDM, 12 May 1924, p. 6

[16] Clive Emsley, Soldier, Sailor, Beggarman, Thief, p. 71-72

[17] HDM, 20 August 1931, p. 5

[18] HDM, 20 August 1931, p. 5

[19] HDM, 20 August 1931, p. 5

[20] HDM, 24 December 1943, p. 4

[21] HDM, 15 May 1920, p. 1

[22] HDM, 21 May 1920, p. 5

[23] HDM, 12 February 1947, p. 4

[24] HDM, 13 February 1947, p. 4 and HDM, 13 November 1947, p. 1

[25] HDM, 9 May 1919, p. 5

[26] HDM, 3 October 1919, p. 3

[27] HDM, 18 November 1950, p. 1

[28] Mick Macilwee, The Liverpool Underworld: Crime in the City, 1750- 1900 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2011), p. 124

[29] HDM, 18 November 1908, p. 6

[30] HDM, 23 May 1946, p. 4

[31] HDM, 19 April 1948, p. 1

[32] HDM, 23 September 1949, p. 1

[34] HDM, 20 April 1920, p.8 and HDM, 12 May 1920, p. 6

[35] HDM, 19 June 1917, p. 4

[36] HDM, 22 March 1920, p. 3

[37] HDM, 24 June 1927, p. 12

[38] HDM, 24 June 1927, p. 12

[39] HDM, 24 June 1927, p. 12

[40] HDM, 12 January 1950, p. 1

[41] HDM, 30 October 1919, p. 8

[42] HDM, 15 November 1912, p. 5

[1] Clive Emsley, Crime and Society in Twentieth-Century England (London: Longman, 2011), p. 24

[2] There are multiple examples of petty offence for a selection see the cases of: Samuel Stirrup, Hull Daily Mail (HDM), 3 June 1904, p. 4; William Pheonix, HDM, 24 November 1905, p. 6; James Richards, HDM, 23 October 1909, p. 2; Emanuel Victor, HDM, 27 December 1909, p. 6; Charles Williams, HDM, 7 September 1910, p. 3

[3] See the case of Price Makaroo, Driffield Times, 27 April 1907, p. 2 and Roland Stowe, HDM, 1 June 1912, p. 6

[4] See the case of: Arnold George Cummings, Hull Daily Mail, 3 June 1909, p. 4; Harrison Baily, Hull Daily Mail, 30 June 1909, p. 3; Ephraim Matthews, HDM, 8 February 1910, p. 5; Weldon Collins, HDM, 22 April 1914; Thomas Melgum (multiple stealing convictions) a selection include: HDM, 23 April 1912, p. 8; HDM, 25 October 1912, p. 5; HDM, 22 Oct 1914, p. 4,

[5] Clive Emsley, Soldier, Sailor, Beggarman, Thief: Crime and the British Armed Serviced since 1914 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 71-72

[6] HDM, 12 September 1916, p. 3

[7] HDM, 11 June 1917, p. 4

[8] HDM, 20 September 1916, p. 3

[9] HDM, 30 September 1918, p. 4

[10] HDM, 24 January 1920, 4

[11] There are various versions of events some newspaper articles advise readers that Carter followed Armitage to his sister’s house and stabbed her before him. However, this was not factored into the charges. See Hull Daily Mail, 30 April 1924, p. 7. Other articles include: Hull Daily Mail, 22, 24 and 29 April 1924.

[12] HDM, 10 May 1924, p. 6

[13] Ibid, p. 6

[14] Ibid, p. 6

[15] HDM, 12 May 1924, p. 6

[16] Clive Emsley, Soldier, Sailor, Beggarman, Thief, p. 71-72

[17] HDM, 20 August 1931, p. 5

[18] HDM, 20 August 1931, p. 5

[19] HDM, 20 August 1931, p. 5

[20] HDM, 24 December 1943, p. 4

[21] HDM, 15 May 1920, p. 1

[22] HDM, 21 May 1920, p. 5

[23] HDM, 12 February 1947, p. 4

[24] HDM, 13 February 1947, p. 4 and HDM, 13 November 1947, p. 1

[25] HDM, 9 May 1919, p. 5

[26] HDM, 3 October 1919, p. 3

[27] HDM, 18 November 1950, p. 1

[28] Mick Macilwee, The Liverpool Underworld: Crime in the City, 1750- 1900 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2011), p. 124

[29] HDM, 18 November 1908, p. 6

[30] HDM, 23 May 1946, p. 4

[31] HDM, 19 April 1948, p. 1

[32] HDM, 23 September 1949, p. 1

[34] HDM, 20 April 1920, p.8 and HDM, 12 May 1920, p. 6

[35] HDM, 19 June 1917, p. 4

[36] HDM, 22 March 1920, p. 3

[37] HDM, 24 June 1927, p. 12

[38] HDM, 24 June 1927, p. 12

[39] HDM, 24 June 1927, p. 12

[40] HDM, 12 January 1950, p. 1

[41] HDM, 30 October 1919, p. 8

[42] HDM, 15 November 1912, p. 5